Ukraine gas negotiations: from ‘win-win-win’ to ‘lose-lose-lose’?

The recent escalation is a costly strategy for both sides. With current infrastructure, Ukraine will only be able to cover about three quarter of

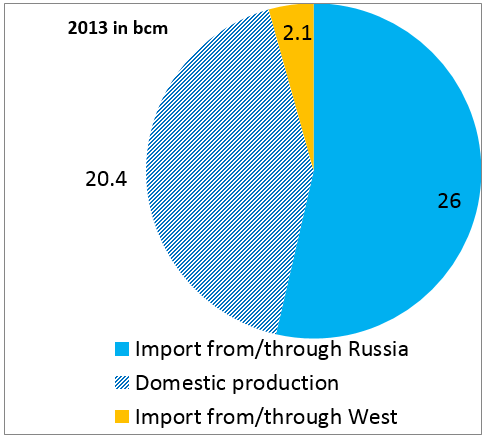

The recent escalation is a costly strategy for both sides. With the current infrastructure, Ukraine will only be able to cover about three quarters of its total consumption (about 50 billion cubic meters [bcm] in 2013) using domestically produced gas (20 bcm) and imports from the West (up to 15 bcm). So, if the issue is not resolved before the winter about a quarter of consumption would need to be curtailed.

For Russia, having no agreement means that past debt (Gazprom claims USD 4.5bn) will not be settled and that Russia loses its 'gas leverage' over Ukrainian politics. Furthermore, the Russian decision to stop gas supplies and not entering another round of negotiations indicates a lacking willingness from Russia to reach a negotiated solution.

This might reinforce the image of Russia using gas as a political tool and hence speed up European moves to diversify away from dependence on Russian gas. It might also strengthen the commitment of Europe to support Ukraine - that is often seen as a difficult and not completely reliable partner - in a gas crisis.

Ukraine gas supply 2013

Source: Ministry of Fuel and Energy of Ukraine

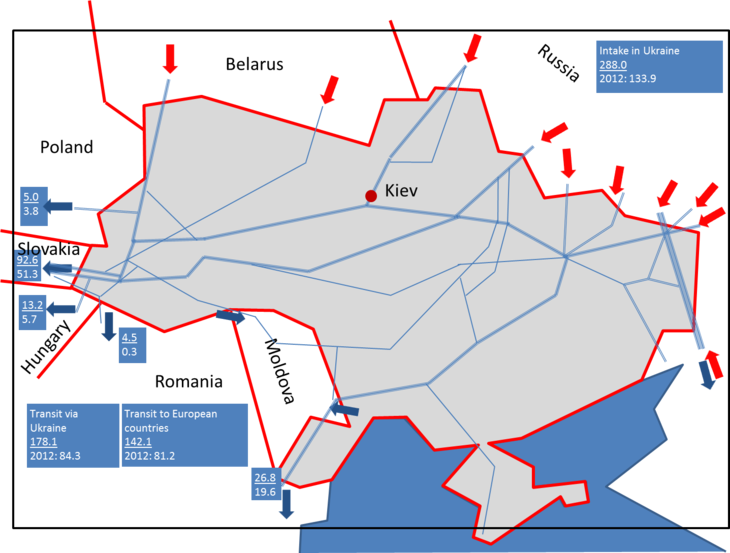

The next escalation step is a stop in transit. Again, both sides would lose from this. Without transit, there is probably not enough gas in Slovakia to sell to Ukraine, hence the country could only cover half of its consumption. Furthermore, Europe would be much less eager to support Ukraine if it were responsible for a cut in supplies.

Ukraine’s gas transit system and border points (capacity and 2012 flows)

Source: Zachmann and Naumenko (2014)

For Russia, not being able to sell some 40-50 bcm to Europe (130 bcm minus the transit capacity of Nordstram and Belarus) might cost Gazprom up to 14 bn USD per year and a cut in transit would further strengthen the notion that Russia is not a reliable supplier. Consequently, neither side would like to be blamed for a disruption in supplies, while either side would like to see the other blamed. Against this backdrop, a neutral monitoring of Russian gas flows into Ukraine - which is currently not happening - is essential to enable Europe to discourage both sides from causing a transit disruption.

If these negotiations were based on economics alone, a mutually beneficial agreement could be expected soon. Especially as the negotiation positions are not irreconcilable – Russia offers about 380 USD/tcm based on an ad hoc export tax rebate, while Ukraine asks for 320 USD/tcm based on a legally enforceable change in contract.

But, when the larger politics enter the negotiations, the result becomes pretty much unforeseeable.

The author is member of the German Advisory Group to the Ukrainian government.