The Russian pipeline waltz

This is an eventful period for EU-Russia gas relations. Six months ago Russian President Vladimir Putin surprised the energy world by dismissing the l

This is an eventful period for EU-Russia gas relations. Six months ago Russian President Vladimir Putin surprised the energy world by dismissing the long-prepared South Stream project in favour of Turkish Stream. Like South Stream, Turkish Stream is intended to deliver 63 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year through the Black Sea to Turkey and Europe by completely bypassing Ukraine from 2019.

Yesterday, during the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum 2015, Gazprom unexpectedly signed a set of Memorandums of Intent with the European gas companies E.ON, Shell and OMV. These plan for the construction of two additional gas pipeline strings along the Nord Stream pipeline system that connects Russia and Germany through the Baltic Sea. This project would double the current capacity of Nord Stream from 55 bcm per year to 110 bcm per year.

Both Turkish Stream and an expanded Nord Stream indicate that Russia does not intend to abandon its position in the European market (by for example shifting attention to Asia).

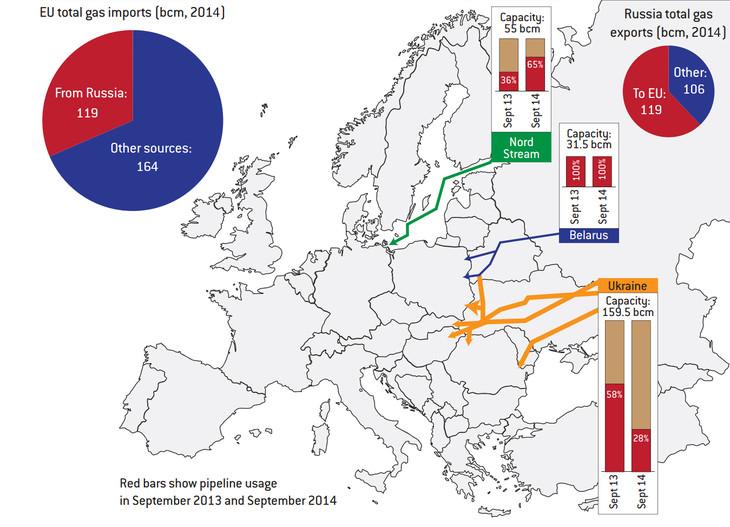

As illustrated in the figure below, current EU-Russia gas trade is based on three key axes: the Nord Stream pipeline, the Yamal-Europe pipeline through Belarus and the pipeline system crossing Ukraine. Of these three routes, only the Ukrainian gas transportation system is not controlled by Gazprom.

EU-Russia existing gas connections

Source: Bruegel based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015, IEA Gas Trade Flows in Europe, Nord Stream website.

Gazprom has asserted several times that it will cut off gas transits through Ukraine by the end of the decade. The current alternative routes (Nord Stream + Belarus), however, only present a capacity of 86.5 bcm per year. To maintain the current level of Russia’s exports (119 bcm in 2014) at least 35 bcm of additional pipeline capacity would be needed.

In fact, current capacities are not being fully exploited due to disputes over the access regime to the OPAL pipeline in Germany which connects Nord Stream to European markets. Gazprom would like to make full use of the pipeline, but the European Commission, the German regulator and Gazprom have not yet reached a decision on the conditions for an exception from the EU's Third Energy Package that would allow Gazprom to control more than 50% of the capacities.

Either Turkish Stream (with its 49 bcm per year devoted to the European market) or an expansion of Nord Stream (55 bcm per year) alone wouldallow Russia to circumvent Ukraine. Both lines together would result in significant over-capacity. So there seems to be a trade-off between Turkish Stream and an expanded Nord Stream.

So, how should the most recent evolutions of the Russian waltz of pipelines be interpreted? There are three possible scenarios:

i) Turkish Stream for Turkey only & Nord Stream for the EU. In this scenario Russia would target the construction of the first string of Turkish Stream to divert the 14 bcm per year currently supplied to Turkey via the Trans-Balkan pipeline (crossing Ukraine, Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria) by 2016, as recently agreed in Ankara. This would allow Russia to capitalize on the massive investments already made in the "Russian Southern Corridor" and to make use of the South Stream pipes already delivered at the Varna harbor and of the pipe-laying ships already placed in the Black Sea. Considering the regulatory and financial barriers to the development of new infrastructure to deliver Turkish Stream gas to EU destination markets, Russia would abandon its plan to supply the EU market via Turkish Stream and rather invest in the expansion of Nord Stream to cover this market.

ii) Nord Stream expansion as a bargaining chip to advance Turkish Stream. In this scenario Russia would propose the expansion of Nord Stream, in order to have another bargaining chip in the negotiations with Turkey (and Greece), and to quickly advance the full Turkish Stream project and ensure better commercial conditions. This would allow Gazprom to avoid further controversies around the OPAL pipeline and to deliver gas directly to southern European markets. This way Gazprom’s ability to sell gas to southern Europe would not depend on additional north-south pipelines under EU rules, and some price-differentiation between the northern and southern market for Gazprom gas could be maintained.

iii) No pipelines, just politics. In this scenario Russia does not intend to develop either the full Turkish Stream (but at most the first string for the Turkish market) or the expansion of Nord Stream. The proposals are thus intended to create political cleavages within the EU, at a moment when the EU is toughening its stance against Russia due to the Ukraine crisis. They create cleavages between northern and southern EU countries (Germany favoured by Nord Stream; Italy and Greece favoured by Turkish Stream); between the EU and Member States (for example Member states’ actions that counteract the Brussels strategy to diversify away fro m Russia); and within EU countries (by causing the interests of governments and energy companies to diverge). In such a scenario, this waltz of pipelines thus represents a new chapter in Russia’s enduring divide and rule strategy vis-à-vis the EU energy market.