The risks for Russia and Europe: how new sanctions could hit economic ties

To play a deterrent role against Russian military action, sanctions would have to be very broad, have a rapid effect and be as coordinated as possible

Against the background of the build-up of troops along the Ukrainian border, Western countries are considering sanctions against Russia. Any new sanctions would come on top of those the West has introduced since Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Partly because of these sanctions, the Russian economy has experienced a lost decade. Russia has built up reserves and reduced its exposure to the dollar, but its economy remains highly dependent on fossil-fuel exports, with the European Union by far its most important trading partner. Despite Russian efforts to build up resilience against further financial sanctions, the unprecedented measures currently under discussion would have a substantial impact on the Russian economy. Meanwhile, different EU countries would be affected to different degrees by sanctions. The EU should design support policies for the most-affected countries to make sanctions against Russia more credible.

Russia’s current account

External pressures, such as the oil price collapse and the financial sanctions in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea, and internal pressures, which increased the budget deficit, explain the collapse of the ruble that started in 2014. Even though it abandoned exchange rate targeting in 2014, the Central Bank of Russia spent close to a third of its reserves shoring up the ruble and in December 2014 increased the interest rate to 17%. Since then, Russia has made considerable efforts to reduce its external position and its exposure to the dollar. Figure 1 shows that Russia had managed to rebuild a substantial international investment position by 2021. Foreign reserves make up a substantial part of Russian external assets.

Part of these reserves are formed by the sovereign wealth fund, which receives oil revenues when the price is above $40 and is intended to limit the effects on the Russian economy of oil price shocks. Russia had a current account surplus of 2.4% of GDP in 2020, forecast to be 5.7% in 2021 – this surplus is limited and fluctuates over the years, but Russia has never had a current account deficit. Oil and gas account for roughly half of Russia’s exports and government revenues, and the ruble fluctuates with the oil price. Using this fund, and by fiscal constraint, Russia has built up foreign exchange reserves to the value of nearly $600 billion, or 40% of GDP in current dollars (Figure 2). For reference, in the euro area, central banks hold the equivalent of $1,200 billion or 9% of GDP. Russia’s tightened national budget means the Kremlin can cover expenses as long as oil sells for at least $44 per barrel, according to international estimates.

Not only has Russia increased its foreign reserves, it has also substantially shifted structure. The Russian economy used to be highly dollarised (partly a reflection of the role of natural resources traded in dollars). Since 2014, the government has sought to reduce the use of the dollar by using the euro for trade invoicing and by shifting its liabilities from dollars to rubles, gold and euros. The share of foreign currency-denominated government debt went from 25% in 2014 to 16% in 2018 (according to the Bank for International Settlements). Despite these efforts, the dollar at 45% of liabilities still accounts for the largest share of Russian total external debt (public and private), still much larger than the 27% share of ruble-denominated assets and liabilities. Overall however, Russia has managed to reduce the weight of its external debt to 32% of GDP, and Russian government debt remains low at 17.9% of GDP in 2021 (nominal GDP at current prices).

Trade and investment

Oil in particular plays a major role, accounting for 47% of Russia’s exports. Natural gas, which is important geopolitically, accounts for another 6% of exports. The share of fossil fuels in exports to the EU is even higher. For the entire EU, imports of oil account for 14% of total imports, 60% of what is imported from Russia. Natural gas accounts for 3%, 9.5% of what is imported from Russia. Notably, 70% of Russia’s exports to Germany are petroleum and coal products; for the Netherlands and Italy, the share is 80% and for Poland 75%. These EU countries export to Russia a significant volume of pharmaceutical products. Beyond this, Germany, Poland and the Netherlands export mainly vehicles and their parts, while Italy exports furniture.

While the EU takes half of Russian exports, its second trading partner, China, accounts for only 14% of exports. But Russia accounts for only 5% of EU trade. In that sense, Russia is much more exposed to trade disruptions with the EU, than the EU is with respect to Russia.

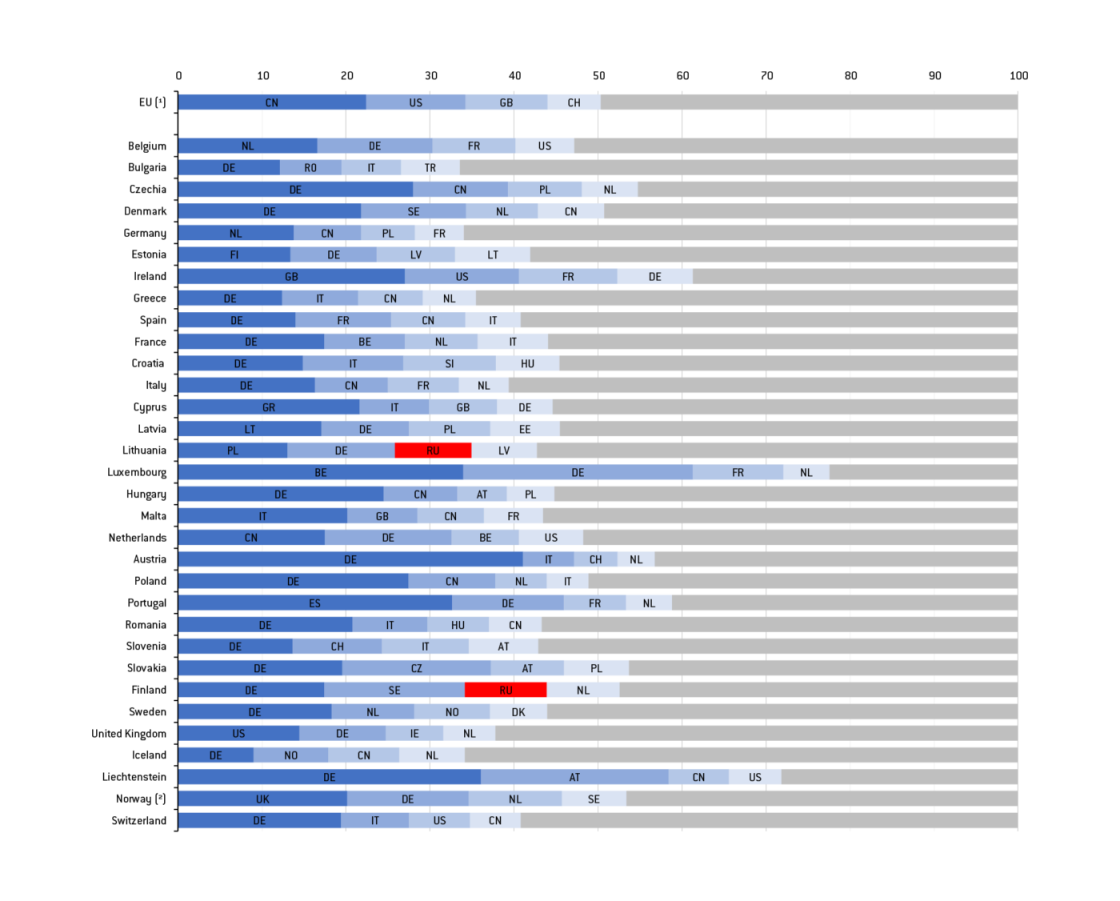

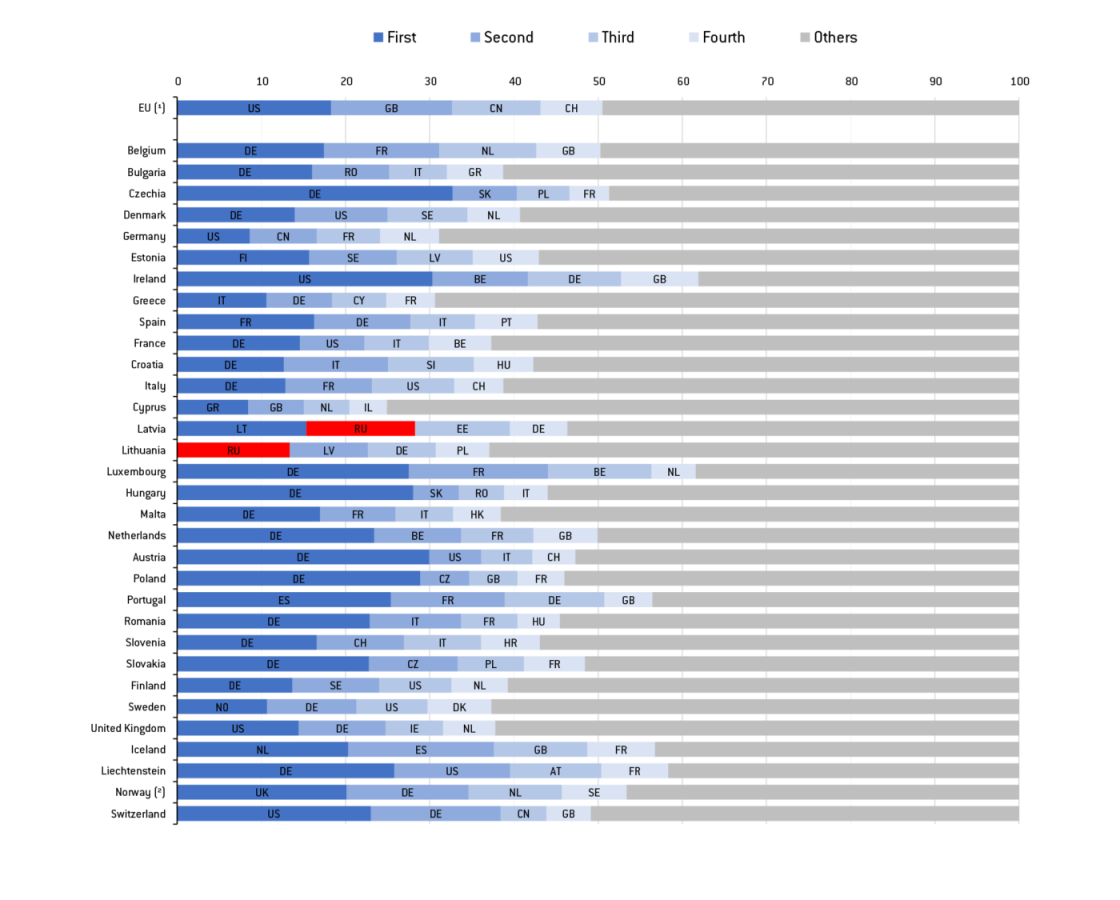

However, there are substantial differences between the trade exposures of EU countries to Russia. Eastern European countries depend more on Russian gas and petroleum. Figure 5 shows that Russia is a major trading partner for Lithuania and Latvia. At 17%, Lithuania had the highest share among EU countries of exports going to Russia in 2019. More than 14% of Finland and 10% Bulgarian exports also go to Russia. Latvia imports the most from Russia in relative terms, and the value of its imports is about 8% of total imports.

Figure 5: Top four trading partners of EU countries; exports (top panel) and imports (bottom panel) of goods, 2020

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat.

In turn, Russia depends in some sectors on imports from the West. Table 1 shows the value of Russian imports of selected high-tech and pharmaceutical products. The EU’s share of Russia’s imports of those goods is approximately 45%, while the United States share is 6%. About 70% of Russia’s imports of chemical products and 60% of imports of instruments and apparatus came from the EU in 2019.

Russia is generally poorly integrated into the global economy. It only joined the World Trade Organisation in 2012 and has concluded 10 trade agreements covering 11% of Russian exports, mostly with former Soviet states. The appreciation of the ruble during the oil price boom in the 2000s created a resource curse for Russia’s manufacturing sector. Given the limits of the domestic market (Russia’s economy is roughly the size of Spain’s) and its very high trading costs (in the World Bank’s Doing Business Report 2018, this was reported as 6.7 times the EU average for exports and 17 times the EU average for imports), the incentives have been limited for foreign investment in manufacturing or services destined for world markets. This is aggravated by corruption and a lack of secure property rights, on which Russia ranks 136 and 81 in international comparisons respectively.

Insecure property rights have also led Russian investors to use foreign investment vehicles to protect their capital from state capture. Estimates of ultimate investing countries (UIC) suggest that a substantial share of foreign direct investment into Russia is Russian money redirected through financial centres. Figure 6 compares the official FDI stock to International Monetary Fund UIC estimates. The EU is anyway the largest foreign investor in Russia, but in the UIC case Russia emerges as the second largest ‘foreign’ investor in its own economy. It is likely that more ultimately Russian capital hides among the offshore investments with non-identifiable origin.

Russian investors mainly reinvest in their own country through European financial centres with accommodative tax regimes. This has also exported corruption and has been used to influence European foreign policy. However, the reliance of Russian investors on European financial centres has also exposed Russian elites to sanctions such as asset freezes.

Sanctions

Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent sanctions coincided with an oil price shock in which the price of Russia’s most important export almost halved. Both contributed to the recession in Russia, but, given their concurrence, it is difficult to discern the contribution of each. While the oil price shock probably had the larger effect on the Russian economy, the IMF estimated that the sanctions reduced Russian GDP by between 1% and 1.5%, and the long-term effects may be even greater, leading to a 9% decrease in GDP. Similarly, in 2016 the World Bank estimated that a lifting of sanctions would have increased economic growth in 2017 by 0.7 percentage points. Although these estimates are debated and cannot be used to anticipate the potential impacts of future sanctions, some impacts have been felt despite the limited nature of the sanctions compared to the measures discussed now. Table 2 summarises sanctions in place and those discussed by the US, EU and Russia itself. The countersanctions that Russia has imposed as retaliation have had only very limited impacts, likely hurting Russian consumers more than European exporters due to the small relevance of the Russian market to the EU.

The sanctions now being discussed are of unprecedented scale. Current sanctions imposed by the US and the EU restrict some trade and financial activities and target specific individual and entities. Examples include a ban on the purchase of Russian government debt, a ban on exports of high-tech goods such as semiconductors, asset freezes and wide-ranging measures against Russian banks. The new sanctions would have a much broader impact and be less ‘surgical’ in the choice of targeted entities. New measures could include targeting NordStream 2 and excluding Russia from SWIFT.

SWIFT is a financial transaction messaging network. The exclusion of Russian banks could severely impact their ability to make cross-border payments. A similar sanction on Iran resulted in a loss of a third of its foreign trade. When excluding Russia from SWIFT was floated in 2014, the Russian government announced the measures could cause a loss of as much as 5% of Russian GDP. On the other hand, there are concerns that such an action could undermine SWIFT’s credibility as a reliable intermediary, with negative consequences over the medium term. As it is headquartered in Belgium, SWIFT falls under EU jurisdiction. However, with Iran, SWIFT followed US pressure despite European resistance.

The European banks with the largest exposures to Russia (Société Générale, Raiffeisen Bank, UniCredit and OTP Bank) saw small drops in their stock prices after to the announcement of the potential tightening up of the sanctions on Russia. However, their stock prices recovered within a few days. A different trend is visible for Russian banks operating in Europe. Figure 8 shows their equity prices, which have been under pressure since the Russian build-up of troops along the Ukrainian border.

Conclusion

Russia’s long-term economic outlook is already rather dire, with a rapidly aging society and an economy reliant on fossil-fuel extraction and lacking integration into global value chains. The wide-ranging Western economic sanctions under discussion, and Russian potential countersanctions, if applied, would weaken this outlook further. Generally, the Russian economy is much more dependent on Western imports than Europe is on Russian exports. However, Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas gives the Kremlin leverage – for this, the EU needs to design a response package that supports the most exposed countries, especially in the Baltics and eastern and central Europe. Furthermore, there is a risk of the tensions escalating into a hybrid conflict with cyber-attacks on critical infrastructure representing a big risk for Europe.

Russia has made efforts to build up foreign reserves and reduce its reliance on the dollar. However, the effectiveness of this strategy in shielding Russia from financial sanctions is questionable, given the centrality for global capital markets of the US financial system. In addition, the use of European tax havens by Russian elites gives Europe options in terms of asset freezes.

Given these links, sanctions have the potential to damage the Russian economy in the short and medium to long term. For sanctions to play a deterrent role against Russian military action, they would have to be very broad, have a rapid effect and be as coordinated as possible among Western allies.

Recommended citation:

Grzegorczyk, M., Poitiers, N., Weil, P. and G. Wolff (2022) ‘The risks for Russia and Europe: how new sanctions could hit economic ties’, Bruegel Blog, 11 February