The Republican Tax Plan

As the Trump administration’s tax plan continues its way through the legislature, we review economists’ and commentators’ recent opinions on the matte

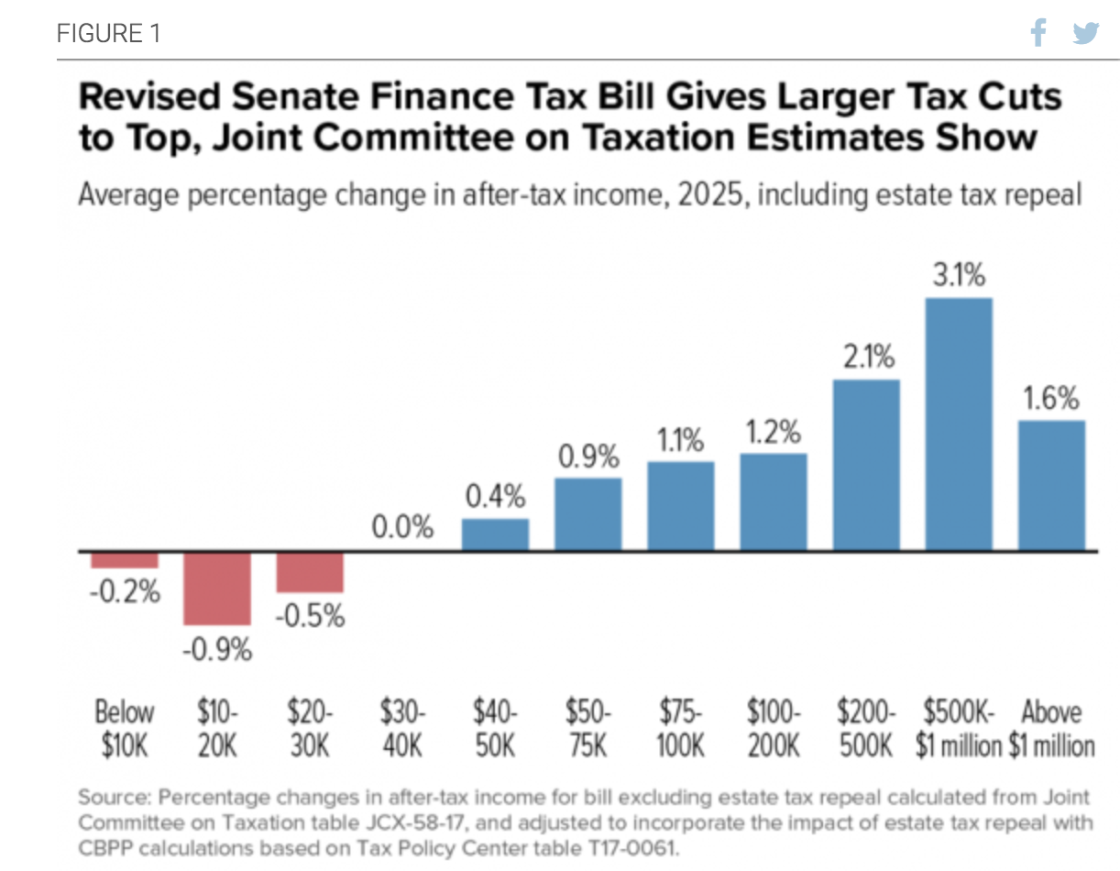

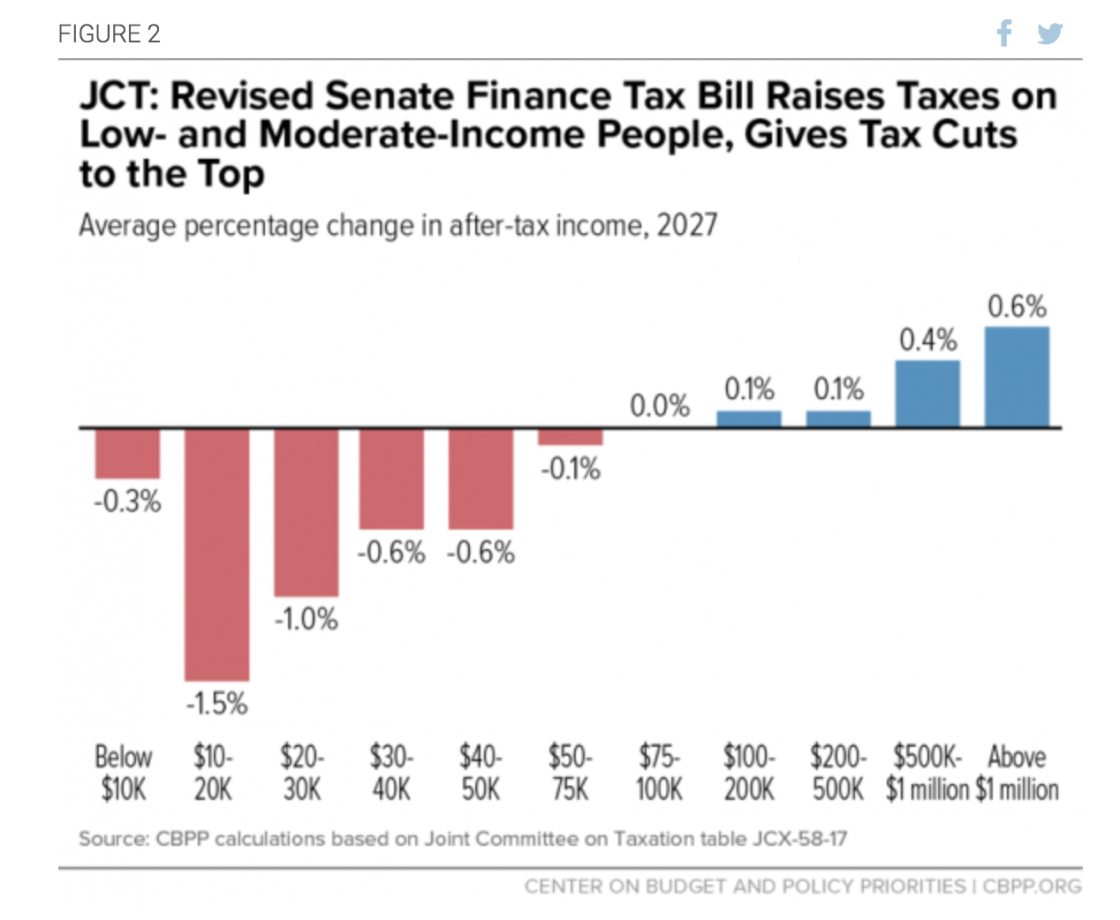

The Penn Wharton Budget Model has analysis (both static and dynamic) of the impact on the federal budget and the economy of both the original and amended House and Senate versions of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA). The Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities looks at the distributional impact, showing that under the amended Senate bill, in 2025 (when most of its provisions would be in place), high-income households would get the largest tax cuts as a share of after-tax income, on average, while households with incomes below $30,000 would on average face a tax increase (Figure 1). By 2027, when many of its provisions would have expired, those at the top would still get large tax cuts, but every income group below $75,000 would face tax increases, on average (Figure 2). Despite raising taxes on millions of middle- and lower-income households, the bill would add $1.5 trillion to deficits over the decade due to its large tax cuts for high-income households and corporations.

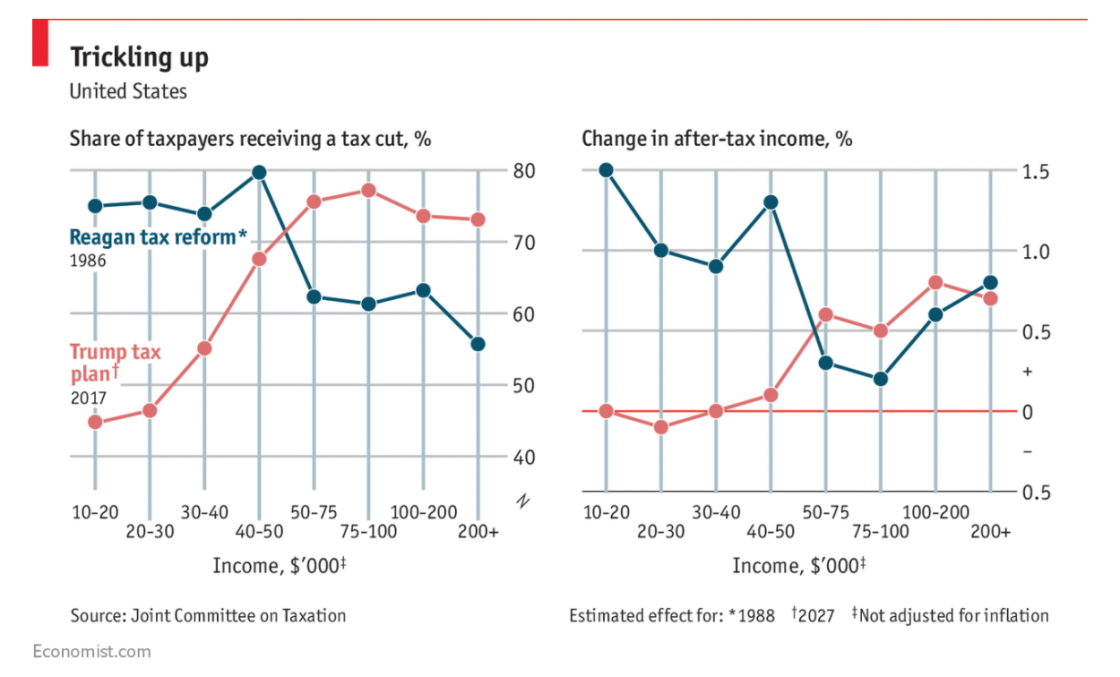

The Economist compares the current administration’s tax plan with the Reagan administration’s Tax Reform Act of 1986, as Republicans embark on yet another sweeping rewrite of the tax code, which many point to as a model to emulate. However, while the authors of the 1986 Act relied heavily on advice from professional economists, President Trump’s Treasury department is yet to find a credible study supporting its claim that tax cuts will deliver enough economic growth to pay for themselves. Instead of seeking bipartisan support, Republicans are using the restrictive procedure of budget reconciliation to try to push the legislation through on a party-line vote.

The substance of the current Republican tax proposal also differs greatly from the 1986 Act. Congressional Republican leaders originally promised that any reform would not reduce the federal government’s overall revenues, but the current plan is expected to raise deficits by as much as $1.5 trn over ten years. And, according to figures from the Joint Committee on Taxation, most of the benefits will go to the rich, unlike Reagan’s reform (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: The Economist

Paul Krugman does not agree with the Trump administration’s claim that cutting taxes on corporate profits would lead to an explosion in private investment and faster economic growth, whose fruits would trickle down to American workers in the form of higher wages. Even if some part of this story were true, there would be side consequences that are not carefully discussed. Nothing in the bill would make Americans consume less and save more, so the money for increased investment would have to come from abroad — from selling stocks, bonds and other assets to foreigners. This inflow of foreign money would drive up the value of the dollar and lead to trade deficits, which would have a devastating effect on manufacturing. Foreign investors would be earning profits and taking them home, so most of any growth coming from cutting corporate taxes would accrue to the benefit of foreigners. Corporate tax cuts wouldn’t actually do much to raise investment, but they would explode the budget deficit. So in an attempt to limit that deficit blowout, Senate Republicans are proposing significant tax increases on working families. Krugman has another post trying to quantify the effects on growth.

Jared Bernstein agrees that the plan is likely to lead to more outsourcing of U.S. jobs and a larger trade deficit. First, the tax plan moves to what’s called a territorial system of international taxation, which means the U.S. tax rate on the overseas earnings of U.S. foreign affiliates would become zero, exacerbating the incentive to offshore jobs. Next, the implausibly large estimates of economic growth allegedly triggered by the plan depend on large capital inflows leading to larger trade deficits. A higher trade deficit doesn’t have to be a drag on growth if other parts of the economy are picking up the slack. But it will unquestionably hurt manufacturers, as the capital flows put upward pressure on the dollar, making exports less price competitive.

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman say the tax plan slams workers and job-creators in favour of inherited wealth. Republicans will claim that cutting taxes on wealthy business owners will boost economic growth and end up benefiting workers down the income ladder. The idea is that if the government taxes the rich less, the wealthy will save more, grow U.S. capital stock and investment, and make workers more productive. The evolution of growth and inequality over the past three decades makes such a claim ludicrous. Since 1980, taxes paid by the wealthy have fallen dramatically and income at the top of the distribution has boomed, but gains for the rest of the population have been paltry. Average national income per adult has grown by only 1.4% per year — a poor performance by both historical and international standards. As a result, the share of national income going to the top 1% has doubled from 10% to more than 20%, while income accrued by the bottom 50% has been almost halved, from 20% to 12.5%. There has been no growth at all in the average pre-tax income of the bottom half of the population over the past 40 years — during which time the trickle-down enthusiasts promised just the opposite.

Angry Bear notices that one of the arguments that Republicans are using to support their tax bill is that it will unleash investment, but the data says otherwise. Currently, most U.S. economic sectors are operating far below maximum capacity utilisation. Right now, it makes far more sense for companies to bring unused capacity back online rather than buy new equipment. Interestingly, mining seems to be the only industry where a boost in investment is possible. The counter-argument is that spare capacity is outdated; as orders increase, companies will be forced to add new, more modern capacity. The problem with this argument is that industrial production is actually very weak, so in order order to see an increase in capacity utilisation, we need industrial production to pick-up.

Martin Wolf says that the Republican tax plan is built for plutocrats. Republicans aim at slashing spending on nearly all of the non-defence discretionary spending of the federal government, plus spending on health and social security. In all, this is a determined effort to shift resources from the bottom, middle and even upper-middle of the US income distribution towards the very top, combined with big increases in economic insecurity for the great majority. How has a party with such objectives successfully gained power? Wolf thinks that we can see three mutually supportive answers to this question. The first approach is to find intellectuals who argue that everybody will benefit from policies ostensibly benefiting so few. Supply-side economics, with its narrow focus on tax cuts, has been the main theory employed, because it directly justifies tax cuts for the very wealthy. But there is powerful contrary evidence. The second approach is to abuse the law. One way has been to give wealth the overriding role in politics that it holds today. Another is to suppress the votes of people likely to vote against plutocratic interests, or even disenfranchise them. The third approach is to foment cultural and ethnic splits. The economics and politics of pluto-populism have stoked cultural, ethnic and nationalist anger in the party’s base. Skilful demagogues are able to exploit this anger for their own purposes.

Richard McKenzie writes on the EconLog blog that critics of the Republican tax plan don't appreciate two major problems with corporate taxes. First, corporations don't pay taxes, people do. These taxes also come partially out of the hides of consumers as corporate managers seek to offset any reduction in after-tax profits by charging higher prices. To the extent that corporate taxes reduce companies' after-tax rates of return, investments in their production facilities will be impaired, curbing supply and further raising market prices. With curbs in corporate production attributable to the corporate tax, the demand for labor can be tempered, undercutting worker wages and fringe benefits. The proposed corporate-tax-rate reduction will likely pad the pockets of the rich by some amount, but it will also increase the disposable income of people all the way down at the bottom of the income ladder. Second, capital – financial and real – and goods and services are now more mobile across national boundaries than ever before. The growth in the mobility of firms, and the greater demands they face to be cost-competitive, means that governments have necessarily been forced to consider in the development of their tax policies the tax rates charged by other countries. The most important, powerful, and least-touted argument in favor of the Republicans' corporate-tax-rate reduction is that the United States has the highest tax rate in the industrial world.

Ryan Bourne at the Cato institute believes that there is a lot for economists to like in the tax bill. On the efficiency and growth front, changes to the income tax code stripped away a whole host of small deductions and made significant inroads into some big ones too, as well as abolishing the AMT. The long-term consequence of the package of these reforms will be a combination of lower rates, fewer deductions and fewer people itemising. This will significantly reduce deadweight costs associated with taxation. The most important policy goal was a large permanent cut in the corporate income tax rate, and Bourne believes this will raise the level of GDP and wages. The other, final change of note is the planned repeal of the estate tax. Bourne argues that critics of the plan were wrong to say this was just about tax cuts without reform. The real debate for conservative economists should be weighing these efficiency gains against the consequences for the public finances.