The puzzle of European Union recovery plan assessments

Identical European Commission assessments that EU countries’ recovery plan cost justifications are ‘medium-quality’ undermine trust in the assessments

The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is the largest component of Next Generation EU, the European Union’s landmark recovery and structural transformation instrument. EU countries must submit recovery and resilience plans, which are assessed by the European Commission and approved by the Council. So far 26 countries (not including the Netherlands) have submitted their plans, of which 22 have been approved. The plans of Hungary, Poland and Sweden (which were submitted in May 2021) and Bulgaria (which was submitted in October 2021) have yet to be assessed and approved.

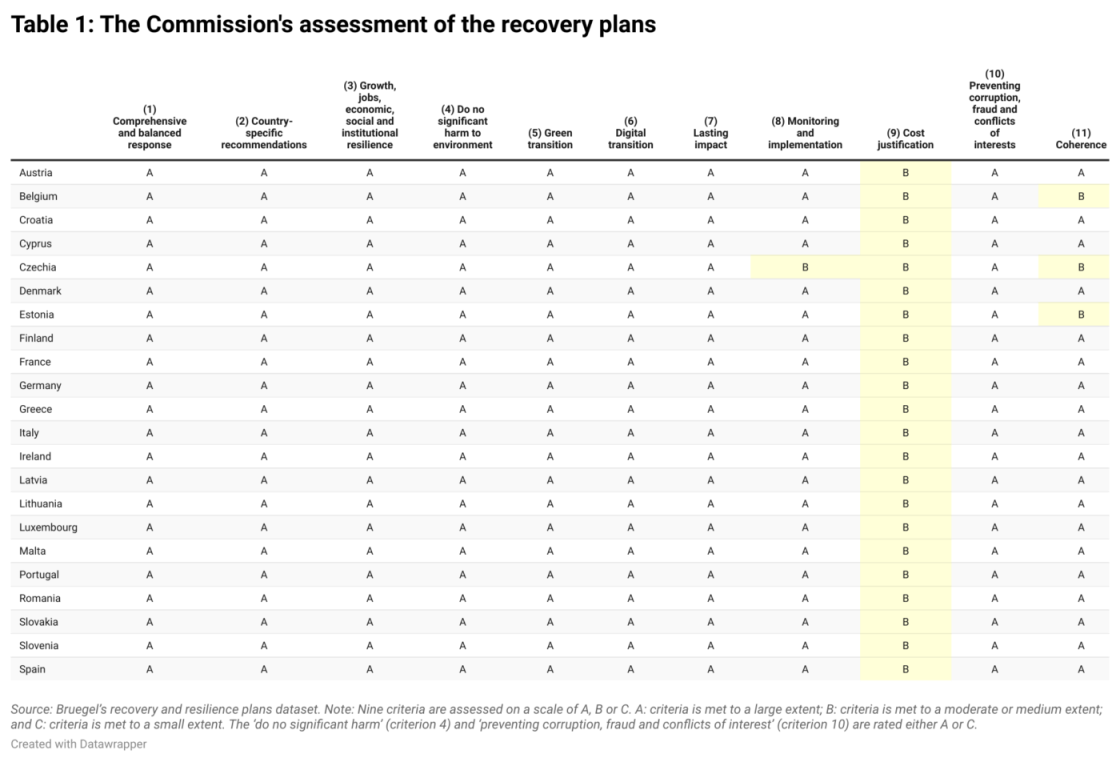

The Commission assesses the plans against 11 criteria defined in Annex 5 to the RRF regulation, including whether they offer a comprehensive and balanced response, properly incorporate country-specific recommendations from the European Semester, foster growth and the green and digital transitions, and include proper cost justifications and adequate measures for prevention of corruption and fraud.

Strikingly, 19 of the Commission’s assessments of the plans are identical, and all countries obtain a B grade for cost justification. There are only one or two differences under other criteria for Belgium, Czechia and Estonia (Table 1).

Several factors create a risk that good value will not be obtained from EU recovery money. The uniform grade for cost justification raises questions about whether this is the outcome of an objective assessment, and even if it is, it implies medium-quality cost planning (Table 1). EU countries do not have experience of using the budgeting method applied for the purposes of the recovery fund – a method with mixed results internationally. The recovery spending targets countries must meet are mixtures of output and result indicators, while different metrics in different countries makes oversight difficult.

The overall ‘good’ quality of the plans is unsurprising: most plans already incorporate significant comments from hundreds of meetings between the Commission and EU countries. However, the cost criterion requires: “The justification provided by the Member State on the amount of the estimated total costs of the recovery and resilience plan is reasonable and plausible and is in line with the principle of cost efficiency and is commensurate to the expected national economic and social impact”. The identical scores against this criterion raise two questions:

- How likely is it that no EU government is able to justify costs to a ‘high extent’?

- What are the implications of a ‘medium quality’ cost justification?

How likely is it that no EU government is able to justify costs to a ‘high extent’?

Here are some of the concerns listed by the Commission for cost justification across all plans:

- Cost breakdowns show varying degrees of detail and depth of calculation;

- There are some gaps in the information and evidence provided on reasonability and plausibility of the estimated costs;

- Sometimes the methodology used is not sufficiently well explained and the link between the justification and the cost itself is not fully clear;

- In some cases, the methodologies and assumptions are less robust;

- Some projects are not sufficiently substantiated with cost of comparable projects, or the evidence cited could not be accessed;

- Did not provide an independent validation for any of the cost estimates proposed;

- Funding criteria and beneficiaries are not sufficiently detailed;

- There is significant potential overlap between the RRF and other EU facilities, but details are not always clear enough or are simply not provided on whether double EU funding will be avoided.

While the text of Commission assessments was most likely drafted very carefully, noticeable differences can be observed across countries. For example, for Italy, there are three paragraphs in the two-page long section assessing cost justification with possible problems. Some examples include:

“The level of detail as regards the methodology and the assumptions made to reach those cost estimates varies across the plan. […] For other measures, the description of the costing estimates is more concise: the methodology and references on the basis of which the costing estimates are based on, are not spelled out with the same level of detail.”

“The estimated costs are plausible, with methodologies and assumptions used varying across measures. […] In a limited number of cases, the methodologies and assumptions are less robust.”

“The information provided by Italy´s recovery and resilience plan in some cases refers to specific type of cost expected to be financed by the various Union programmes, but details are not always clear enough or simply not provided.”

In contrast, for Austria, there is only one critical sentence with a justification:

“In cases where funding criteria and beneficiaries are not yet sufficiently known, expected values for the costs are rated to be reasonable to a medium extent” (note: the Italian assessment does not provide information about whether funding criteria and beneficiaries have been specified).

Another sentence gives a partial medium extent assessment of a component but with no reason:

“In the Austrian plan, all individual cost estimates are assessed to be plausible to a high or medium extent.”

All other sentences praise the cost justification of the Austrian plan.

Similar differences in the tone of the Commission’s detailed assessment can be observed for other countries too, despite the uniform B grade.

So, even the Commission’s detailed assessments suggest differences between countries. It is unlikely that no EU government can justify costs properly. National finance ministries and development banks must have proper experience in cost planning. It also seems implausible that there were no cross-country variations in the quality of cost justification. It could be that countries that receive relatively small amounts had less trouble putting plans together than countries receiving larger amounts, potentially affecting the quality of cost justification. The hypothesis that it was a deliberate decision to grade cost justification at B for all countries cannot be excluded. But if this is correct, how can the assessments be trusted?

What are the implications of a ‘medium quality’ cost justification?

It is important to remember that, unlike other EU programmes, the RRF is performance-based: payments will be made against meeting milestones and targets not by submitting invoices. Hence the actual cost of implementation does not matter.

Spain was the first country to request a payment from the RRF in November 2021 after meeting 52 milestones. These include “Adoption of the National Strategy for Green Infrastructure, Connectivity and Ecological Restoration”, “Entry into force of Action Plan to tackle youth unemployment”, and “Financial Transaction Tax”. For later payments, numerical targets will have to be met, such as completing “at least 25 projects to promote sustainable mobility, in 150 urban and metropolitan areas with more than 50 000 inhabitants” and “completion of residential dwelling renovation actions, achieving on average at least a 30 % primary energy demand reduction (at least 231 000 actions in at least 160 000 unique dwellings)”. There are 416 milestones and targets altogether for Spain listed here.

Performance-based programmes make sense. A 2019 Bruegel report on cohesion policy reform called for a wider use of the financing not linked to costs (FNLTC) method, under which payment depends on fulfilment of conditions or on the achievement of results. But financing of the whole RRF on FNLTC is a giant leap, for two reasons:

First, EU countries have almost no experience in using the FNLTC method for EU-funded projects (even if some have tried similar approaches in national budgeting). FNLTC was introduced in the Financial Regulation of the EU budget in 2018, yet the European Court of Auditors (ECA) has highlighted weaknesses in both design and implementation (paragraphs 51-54 here). A 2021 ECA report noted that while EU countries could use FNLTC in the final two years of the 2014-2020 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), they did not, with the sole exception of Austria, where one pilot project using FNLTC was launched (paragraph 93 and Box 8). The Commission and ECA assessed the reasons for this lack of interest (late introduction of FNLTC, burdensome setup, concerns about their legal certainty of subsequent checks and controls), yet this doesn’t change the lack of experience using FNLTC for EU-funded projects.

Second, a global comparison of results-based budgeting experiences is not encouraging. An extensive World Bank report of seven countries (Australia, Estonia, France, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia and the US) found “a general pattern of disappointment with the results of performance budgeting, balanced by a strong belief in the underlying logic”. Thus, the design and implementation of results-based budgeting, including FNLTC, is not straightforward.

Several ECA reports have highlighted that existing performance-based instruments for the EU budget do not focus on results, but rather on outputs and inputs. The distinction between ‘results’ and ‘outputs’ is key. ECA defines these terms as:

- “A result is a measurable consequence deriving – directly or indirectly – from a cause and effect relationship. The results-based approach to public policy relies on the principle that the focus of public interventions should be on the delivery of results, rather than on activity or process management.”

- “Outputs are produced or accomplished with the resources allocated to an intervention (e.g. training courses delivered to unemployed young people, number of sewage plants or km of roads built, etc.).”

For example, building a bridge is an output. The consequent reductions in commuting time and car emissions are results. The same output can lead to good results (a bridge in a well-chosen location) or bad results (a bridge in a poorly chosen location).

ECA also emphasised the importance of common indicators in measuring results, so that country-specific data can be aggregated to the EU level. In line with the RFF regulation, the Commission adopted a delegated regulation specifying 14 common indicators for reporting, monitoring and evaluation, which are to be displayed in the scoreboard. These indicators include results, such as savings in annual primary energy consumption, and outputs, like the number of enterprises supported to develop or adopt digital products, services and application processes.

In my assessment, the quantitative targets in national recovery plans vary significantly, limiting cross-country comparability. The 14 common indicators allow that, but cover only a subset of the activities financed by the RRF. Moreover, many target indicators reflect outputs rather than results. For example in the Spanish recovery plan, there are multiple targets including: funds spent on purchases or awarded by municipalities/Autonomous Communities, the number of projects completed, or the number of roads improved (moreover, measure C1.I1 requires that at least 34 state roads be improved without specify the minimum length of the road or improvement). Similar examples exist in the recovery plans of other countries.

Summary

The diversity of recovery plan milestones and targets and the mixture of output and results indicators make cross-country comparison problematic. Assessment of the ease of achieving milestones and targets across countries is also difficult. This is coupled with the lack of experience of EU countries in applying the financing not linked to costs (FNLTC) method to EU-funded projects and generally mixed global experiences in performance-based budgeting. On top of all these issues, no country was able to justify the costs of the recovery plan to a high extent according to the European Commission, questioning the objectivity of the Commission’s assessments. These factors create the risk that recovery money might not be spent in a cost-efficient way, necessitating very careful assessments of not just the outputs, but also the results and value for money. Beyond official bodies, citizens should also be vigilant about how this money is spent.

Recommended citation:

Darvas, Z. (2022) ‘The puzzle of European Union recovery plan assessments’, Bruegel Blog, 8 February