Promoting intra-regional trade in the south of the Mediterranean

Regional integration is still a sure way for economies in development to achieve economic growth on the global market. The south of the Mediterranean

Despite the recent narrative of trade protectionism, free and open trade is accepted as the right means to promoting growth and prosperity. And regional trade integration is the first step to opening markets and benefiting in terms of welfare.

We show that trade integration in the south of the Mediterranean (MED) is still very low and incomplete. There are important economies of scale and diversification opportunities that remain largely unexploited. At the same time there are several trade agreements, some say too many, but they have not been able to create the necessary conditions for trade to ultimately develop. However, none of the existing economies of scale or necessary conditions for trade can be created before peace, political stability and economic security are re-established.

There is a clear role that Europe could play here. European countries have been actively involved in the region, but the next step in promoting the region’s development will rely on (more) coordinated action. This will be necessary for promoting intra-regional trade.

Trade integration in the region: low and incomplete

The EU is by far the most significant trading partner of MED countries. Figure 1 shows that the EU attracts more than half of Algerian, Libyan, Moroccan and Tunisian exports, and also accounts for a large share of Egypt’s exports. Energy trade is arguably the most important economic link between the two regions.

Imports are slightly less concentrated. In the last years, while Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia reduced their high dependence on EU products (around 50%), Libya and Egypt significantly increased imports from European countries.

Simultaneously, the economic rise of China and India has been a mixed blessing for the countries in North Africa. One the one hand, higher demand from these countries has partially offset the reduced European demand coming from the crisis. On the other hand, domestic producers and exporters have seen an increase in competitions from China and India, especially in the textile and electronics industries.

But a striking feature of the Southern Mediterranean countries is the uncharacteristically low level of intra-regional integration, shown in figure 2. Intra-regional trade represents only 5.5% of total exports and even less (3.9%) of total imports. According to the African Development Bank (2012), it has been the lowest of any region in the world and well below that achieved by other regional communities in Africa, such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) or the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

There are a number of reasons that point to this lack of regional trade. First, the region’s modest income and size compared to neighbouring Europe makes it gravitate towards it. Close links with Europe mask the need to develop stronger regional links.

Second, it reflects the lack of complementarity in production structures of countries in the regions. However, Chaponnière and Lautier (2014) point out the success of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) model is based on intra-industry regional trade rather than inter-industry. Ben Ali (2016) also agree on how the region can benefit from developing intra-industry trade and upgrade their respective export quality.

Beyond these structural constraints, there are various infrastructure-related and policy-induced impediments to intra-regional trade. Shepherd (2011) reports the perverse effect of North African countries having lower costs when they trade with Europe than when they trade between them. Trade costs between Maghreb ranged from 335% of production value in 1995 to 278% in 2014, about twice as high as trade costs with European states. This is due to the relatively few active transport corridors across the region and the existence of fragmented logistics services markets. The World Bank (2013) reports that improving logistic performance would reduce average bilateral trade costs by a factor of ten compared to an equivalent percentage reduction in average tariffs.

Finally, non-tariff measures, like complicated customs clearance and overburdened administrative processes, still represent a relevant hurdle, as reported by the International Trade Centre (2015). Another impeding factor to intraregional trade relates to restrictive rules of origin. According to the OCP Policy Center (2016), diagonal accumulation only exists across a subset of countries and generally differs across some Euro-Med countries (e.g. the ROOs for Egypt are not the same as those for Tunisia and Morocco), which further restricts effective market access to the EU.

Last, political instability throughout North Africa and the region more general, has not helped the cause of economic growth and integration. Firstly, Algeria and Libya have very unpredictable environments for foreign operators, a clear disincentive to mutual trade and investment. Secondly, there is latent hostility, on account of the Western Sahara, between Algeria and Morocco which led to the closure of the Algerian-Morocco border since 1997. In practice, this has severely restricted the flow of goods and people between the two nations and probably represents the largest literal barrier to economic integration in the region (see the report for the European Parliament by Jolly 2014).

Trade agreements an obstacle to trade integration?

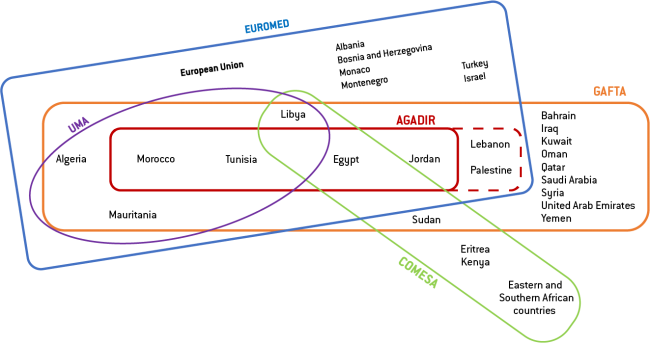

The low level of integration contrasts with the numerous regional trade agreements that span the region. Figure 3 provides a graphic representation of North African countries’ membership in various Regional Economic Communities and how they overlap.

Analysts (e.g. Hoekman, 2016, and Wolf et al, 2017) agree that the proliferation of (often overlapping) trade arrangements has actually led to negative results due to an accumulation of rules that are largely inconsistent in application and scope. In particular, the diverse rule of origin systems is considered a major impediment to creation of integrated supply chains in the region.

Initiatives aimed at regional integration such as the GAFTA (Greater-Arab Free Trade Area) and the AMU (Arab Maghreb Union) have not met expectations mainly due to lack of implementation and the persistence of non-tariff measures. Nevertheless, the EU has regarded the Agadir Agreement as the most promising way of enhancing South-South integration. Despite the rather limited effect of the process, the EU has supported the setting up of Agadir Technical Unit. According to Behr (2010), part of the EU’s enthusiasm for the Agadir Process over GAFTA stems from the fact that Agadir links closely the southern Mediterranean countries to the EU. Thus, the Agadir countries adhere to the Pan-Euro Med Rules of Origins and apply the so-called Euro Med certificates to their exports. In light of this, a few positive developments are worth noticing: last year Palestine and Lebanon joined the Agadir Agreement and recently Egypt officially declared its intentions to revive the agreement, given the tension between Egypt and some Gulf states.

Contrary to the intention of free trade agreement of homogenising standards and increasing cooperation, agreements in the region have not had the desired effect. Improving that requires expanding the scope of existing agreements to include more countries.

A role for the EU?

In line with the G20 agenda, the role of the EU in the region is both crucial to its own interests and pivotal for the MED region itself. But the issues and EU involvement are not new. Development banks are already present in the region and European countries themselves have their own established ways of contributing.

We feel that the EU’s role could be strengthen in the following ways:

First, coordinate efforts from the European side to maximise the breadth and depth of help provided. This may require centralising at least a part of national efforts made in order to ensure consistency and aim at priority objectives.

Second, the issue of coordination needs to happen also in terms who Europe engages with. Studies show (Jolly, 2014), that when the EU engages bilaterally with the countries of the region, it runs the risk of reinforcing non-cooperative behaviour. This means that each MED partner prefers to conduct its own negotiations to extract preferential treatment in direct competition with its own neighbours. This is an important limitation to the “hub-and-spoke” relationship with the EU. Preventing that, will require the EU encouraging interregional talks (EU-MED) rather than directly with individual countries. This by itself can help centralise cooperation and refocus the number and focus of current trade agreements.

Third, the EU should continue helping regional organisations function more effectively within the limited margin set by the political process, and with that demonstrate its commitment to South-South integration. However, funds currently earmarked for regional cooperation schemes probably fall far short of what would potentially be needed.

The sustainable development of south Mediterranean countries is a strategic long-term investment for the EU not only for economic relations but also for containing the migratory waves from the rest of Africa, that will continue to increase in the future (Dadush et al 2017). Intra-regional trade integration is in our view a key and unexploited way of future development.

References

African Development Bank, 2012. Unlocking North Africa's Potential through Regional Integration: Challenges and Opportunities.

Ali, M.S.B. ed., 2016. Economic development in the Middle East and North Africa: Challenges and prospects. Springer.

Behr, T., 2010. Regional integration in the Mediterranean moving out of the deadlock? Notre Europe.

Chaponnière, J.R. and Lautier, M., 2016. By chance or by virtue? The regional economic integration process in Southeast Asia. In ASEAN Economic Community (pp. 33-57). Palgrave Macmillan US.

Dadush, U., Demertzis, M., and Wolff, G., 2017. Europe’s role in North Africa: development, investment and migration, Bruegel Policy Contribution No. 10, Paper presented at the Informal Ecofin in Malta, April 2017.

El Aynaoui, K., El Mokri, K., Dadush, U. and Berahab, R., 2016. The Unmet Challenge of Interdependence in the EU-MENA Space: A View from the South. Seven Years after the Crisis: Intersecting Perspectives, p.35.

Hoekman, B., 2016. Intra-Regional Trade: Potential Catalyst for Growth in the Middle East. Middle East Institute Policy Paper 2016-1.

International Trade Centre, 2015. Making regional integration work: Company perspectives on non-tariff measures in Arab States.

Jolly, C., 2014. Regional integration in the Mediterranean, impact and limits of Community and bilateral policies. In-Depth Analysis requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs.

Shepherd, B., 2011. Trade Costs in the Maghreb 2000- 2009. Developing Trade Consultants Working Paper DTC-2011-9.

Wolf, N., Mihram, F. and Frische, M., 2017. Perspectives on Economic Integration between the EU and North Africa: Investments, Reforms, Partnership. Humboldt University of Berlin, Institute of Economic History, mimeo.

World Bank, 2013. Trade Costs in the Developing World: 1995–2010. Policy Research Working Paper 6309.