The persistence of slow growth

What’s at stake: The persistence of slow economic growth in the Great Recession has been puzzling. Two recent papers have tried to present a coherent

Story one: Hysterisis and Superhysterisis

Olivier Blanchard, Eugenio Cerutti and Lawrence Summers write that a surprisingly high proportion of recessions, about two-thirds, are followed by lower output relative to the prerecession trend even after the economy has recovered. Perhaps even more surprisingly, in about one-half of those cases, the recession is followed not just by lower output, but by lower output growth relative to the prerecession output trend. That is, as time passes following recessions, the gap between output and projected output on the basis of the prerecession trend increases. If these correlations are causal, they suggest important hysteresis effects and even “superhysteresis” effects (the term used by Laurence Ball (2014) for the impact of a recession on the growth rate rather than just the level of output).

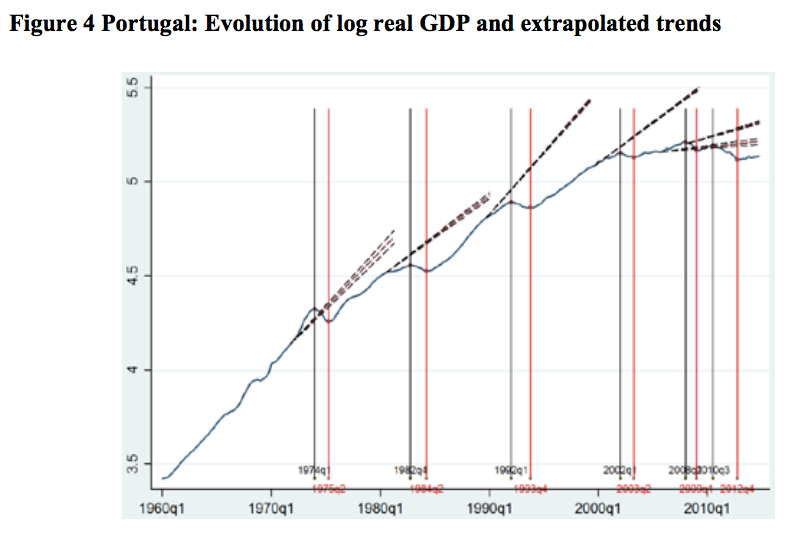

Olivier Blanchard, Eugenio Cerutti and Lawrence Summers write that the evolution of Portugal is representative of the evolutions of a number of European countries. All but one of the recessions since 1960 appear to be associated not only with a lower level of output relative to trend, but even with a subsequent decrease in trend growth, and thus increasing gaps between actual output and past trend.

Olivier Blanchard, Eugenio Cerutti and Lawrence Summers write that it is difficult to think of mechanisms through which the recession leads to lower output growth later, i.e. to “superhysteresis”. Permanently lower output growth requires permanently lower total factor productivity growth; the recession would have to lead to changes in behavior or in institutions, which lead to permanently lower research and development or to permanently lower reallocation. These may range from increased legal or self-imposed restrictions on risk-taking by financial institutions, to changes in taxation discouraging entrepreneurship. While these mechanisms may sometimes be at work, the proportion of cases where the output gap is increasing seems too high for this to be a general explanation.

Story 2: The global safe asset shortage at the ZLB

Ricardo Caballero, Emmanuel Farhi, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas wrote in previous research that global imbalances were primarily the result of the great diversity in the ability to produce safe stores of value around the world, and of the mismatch between this ability and the local demands for these assets. In particular, the authors highlighted the US as the main producer of (safe) assets, and China, oil-producing economies and Japan as the main sources of demand for these stores of value. The growing global shortage of safe assets imparted a strong downward secular trend to world real (safe) interest rates for more than two decades. Capital flows acted as the propagating mechanism by which the asset-scarce regions dragged asset-rich regions’ interest rates down.

In a new research paper, Ricardo Caballero, Emmanuel Farhi, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas write that with unprecedented low natural interest rates across the world following the Great Recession the equilibrating mechanism they highlighted in previous work has little space to operate. Once real interest rates cannot play their equilibrium role any longer, global output becomes the active margin: lower global output – by reducing income and therefore asset demand more than asset supply – rebalances global asset markets. In this world, liquidity traps emerge naturally and countries drag each other into them.

Ricardo Caballero, Emmanuel Farhi, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas write that countries with large safe asset shortages run current account surpluses and drag the world interest rate down. Once at the ZLB, the global asset market is in disequilibrium: there is a global safe asset shortage that cannot be resolved by lower world interest rates. It is instead dissipated by a world recession, which reduces income and therefore asset demand more than asset supply. In this environment, surplus countries push world output down, exerting a negative externality on the world economy.

Paul Krugman writes that international capital mobility makes a liquidity trap in just one country less likely, but it by no means rules that possibility out. The equalization of Japanese real rates with those of the rest of the world didn’t, for example, occur through an equalization of Wicksellian natural rates following a depreciation of the currency. Instead, what happened was that persistent deflation in Japan, combined with the zero lower bound, kept the actual real interest rate well above the Wicksellian rate.