How COVID-19 is laying bare inequality

COVID-19 is laying bare socio-economic inequalities and could exacerbate them in the near future. The virus is a risk factor particularly for those at

The COVID-19 crisis shows how the more vulnerable socio-economic groups suffer from a greater risk of financial exposure, and also from greater health risks, and worse housing conditions during the lockdown period, potentially exacerbating inequalities.

As governments in Europe start to address the emergency with fiscal measures (Anderson et al 2020), understanding how the different socio-economic inequalities intertwine will be of fundamental relevance for policymakers.

Depending on their income and whether or not their economic sector is locked-down, workers are exposed to different risks. Some in lower-income percentiles continue to work and receive their salaries. Examples include healthcare workers and workers in critical supply chains (food, pharmaceuticals, deliveries, essential industries and services). They are exempt from lockdowns but expose themselves to risk of infection by not working from home.

But many other lower-income workers cannot work from home but are also not allowed to go to work. US statistics data shows how the ability to work from home is strongly related to which income percentile an individual is in.

Home working during the quarantine is thus in most cases reserved to those in the highest income deciles. Industrial workers, retail and transport workers are unlikely to have this option, which would allow them to maintain their levels of income, or at least a decent proportion of it, during the shock. The implication for some workers is that they might have to choose between exposure to greater risk by not giving up their wage, or receiving an income shock that, relatively, would be on average greater than that experienced by the higher deciles. In addition, lower-income households have worse financial buffers, and less capacity to borrow or save, which is likely to compound the income shock in the medium and longer terms.

The trade-off between income and risk of exposure seems particularly stark where there are strongly dual labour markets. Workers on temporary and precarious contracts, and the self-employed, often have the least labour protection and contractual bargaining power. The risk of layoff during and after the emergency is particularly high for these categories.

Workers in the gig economy clearly face greater risks during the lockdown: gig-economy workers involved in the delivery of food and other products are particularly exposed. Figure 1 shows the proportion of temporary contracts by employment status in the European Union. It shows how the risks linked to temporary contracts are mainly borne by people in lower-skilled and lower-income occupations. Workers employed in these different occupations will be subject to greater economic and health risks, compared to workers of other statuses.

Source: Eurostat LFS (values in %), 2018.

Other types of vulnerable workers, who will likely be affected the most by the COVID-19 shock, operate in the informal economy. This could be particularly relevant for a country such as Italy, given the size of its informal economy. Workers who are part of the agricultural supply chain and caregivers, who already lack labour protection and unionisation, could face particular challenges.

Other aspects to take into account during the COVID-19 crisis are inequalities in living conditions and neighbourhood quality for those quarantined and for lower-income workers. Different types of inequalities are intertwined with one other, and are likely to increase the cost of the COVID-19 shock in different ways.

Lockdown measures have different effects on quality of life and wellbeing, depending on the state and type of dwelling of locked-down people. If the COVID-19 shock is contained by lifting and reapplying lockdown measures in waves (Ferguson et al, 2020) over the next months, housing conditions might assume even greater importance.

Income levels are related to the available squared metres per capita. In the euro area, individuals living in the top-income households have on average almost double the space as those living the bottom decile – 72 square metres against only 38 (Figure 2).

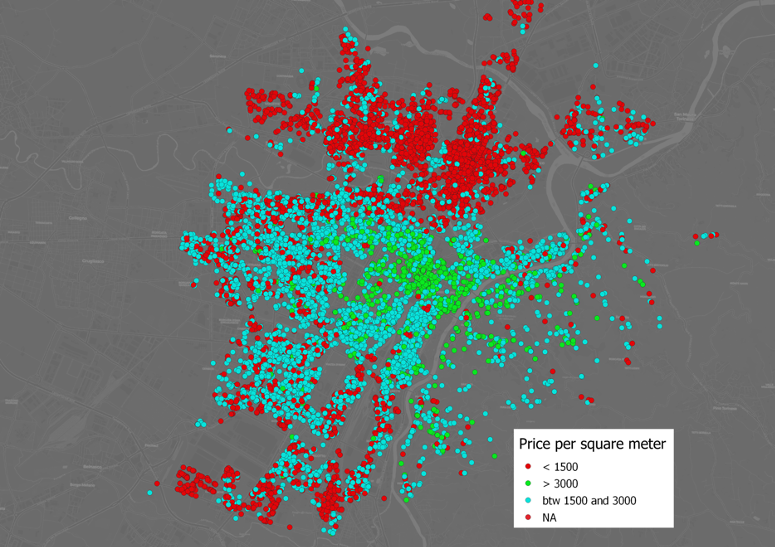

Differences in neighbourhood quality (value of housing stock and related socio-economic indicators) might interact with labour-market inequality in affecting more vulnerable socio-economic groups, especially in crisis times. To illustrate this, we looked at the city of Turin, using data on the housing stock (taken from real estate for sale on a popular Italian website), and census data from the Italian Institute for Statistics (Figure 3). The map shows 15,000 properties categorised according to selling price per square metre (low, high and medium: red, blue and green, respectively). The map highlights the presence of a central area (including the south-eastern part closer to the hills), a residential and a peripheral area. These prices reflect the conditions of the housing stock and the values of homes, arguably a good proxy for neighbourhood incomes and occupations.

Figure 3: Properties by selling price in Turin (2020)

Source: Bruegel (2020). Stock of housing for sale by price bracket. Given an average construction cost per square metre of around €1500 in Italy, properties are categorised into below €1500 (red), between €1500 and €3000 (turquoise), and over €3000 per square metre (green).

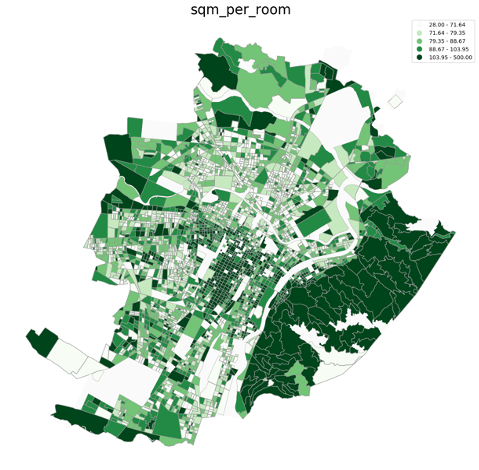

In Figure 4, we observe how in the neighbourhoods with lower selling prices (and incomes) average per-room square metres are lower, confirming the distributions of Figure 2 at the neighbourhood’s level. In addition to higher population densities, there could be a differential size effect between incomes, that can impact the lockdown conditions. Thus, communities in lower-income neighbourhoods, have access to lower-quality housing stock in more densely populated areas.

Figure 4: Square metres per room by census area in Turin

Source: ISTAT census data (2011). Average square metres per room

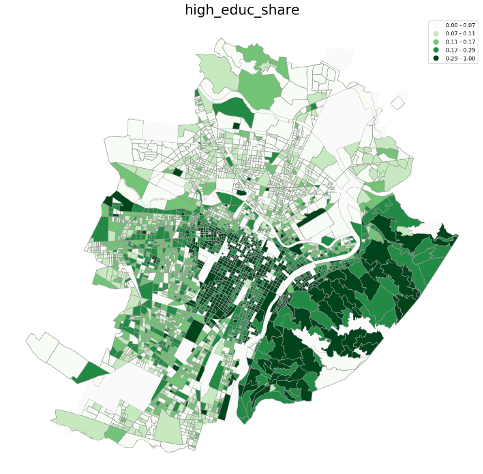

Educational level is a proxy for the socio-economic situations and well-being of individuals (for example, Corak 2013 and Magnouson 2004). Figure 5 shows proportion of the population in Turin with higher education, correlating well with the housing stock data (the best educated live in most expensive, least densely-populated areas). In neighbourhoods where income, education and housing quality are worse, workers are more likely to belong to the occupations with temporary contracts, and less likely to be home-working (Table 1). Therefore, the cost of the shock for these individuals is likely higher in terms of economic and health risks.

Figure 5: Share of individuals with higher education in Turin

Source: ISTAT census data (2011). Share of individuals with higher education (% of total residents)

From the literature, we also know that lower neighbourhood quality and lower incomes are associated with higher incidence of common mental health disorders (Fone et al, 2013; Sareen, 2011; Adler et al, 2016; Kelley-Moore et al, 2016), and domestic violence (Bonomi et al, 2019). In the context of higher financial and psychological distress because of COVID-19 and the consequent prolonged lockdown measures, this aspect of urban inequality might be exacerbated.

Clearly, the dimensions we considered in observing income and urban inequalities, fail to capture highly marginalised and vulnerable socio-economic groups: migrants and asylum seekers, inmates, homeless. Social distancing security measures are almost impossible to be maintained, hence, contributing to a much larger exposure to the sanitary risk of people belonging to the already most vulnerable socio-economic groups. The current situation in the Moira hotspot – in the Greek island of Lesbos – is an extreme example of this highly-concerning situation, in which the COVID-19 crisis can hit where the hygienic, economic, psychological and social conditions are already on the brink of collapse.

In conclusion, poor neighbourhoods and individuals are particularly affected by the COVID-19 crisis. They are more exposed to health risks because they work in critical sectors. They are less likely to be able to work remotely, putting their incomes and jobs at higher risk. They have smaller apartments and live in more densely populated neighbourhoods, exposing them to greater health risks. Finally, they have smaller savings (if at all), giving them smaller buffers. COVID-19 is laying bare different types of interrelated inequality and policymakers, during and after the emergency, should incorporate the understanding of these mechanisms into their policy response.

References

Adler, N.E., Glymour, M.M. and Fielding, J., 2016. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. Jama, 316(16), pp.1641-1642.

Bonomi, A.E., Trabert, B., Anderson, M.L., Kernic, M.A. and Holt, V.L., 2014. Intimate partner violence and neighborhood income: a longitudinal analysis. Violence against women, 20(1), pp.42-58.

Corak, M., 2013. Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), pp.79-102.

Ferguson, N.M., Laydon, D., Nedjati-Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M., Bhatia, S., Boonyasiri, A., Cucunubá, Z., Cuomo-Dannenburg, G. and Dighe, A., Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand.

Fone, D., Greene, G., Farewell, D., White, J., Kelly, M. and Dunstan, F., 2013. Common mental disorders, neighbourhood income inequality and income deprivation: small-area multilevel analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(4), pp.286-293

Hazans, M., 2011. Informal workers across Europe: Evidence from 30 European countries. The World Bank..

Kelley-Moore, J.A., Cagney, K.A., Skarupski, K.A., Everson-Rose, S.A. and Mendes de Leon, C.F., 2016. Do local social hierarchies matter for mental health? A study of neighborhood social status and depressive symptoms in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(2), pp.369-377.

Magnuson, K. A., Meyers, M. K., Ruhm, C. J., & Waldfogel, J. (2004). Inequality in preschool education and school readiness. American educational research journal, 41(1), 115-157