Goodbye Glasgow: what’s next for global climate action?

After COP26, and as the debate on whether Glasgow represents a success or a failure dies down, what next for global climate action?

The world is on track for a 2.4°C global temperature increase above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century if countries stick to the 2030 emissions reduction targets (in jargon, nationally determined contributions, NDCs) they submitted in Glasgow (CAT, IEA, UNEP). This is bad news, as the science has made clear that to avoid the most dramatic consequences of climate change, humanity needs to keep the global temperature increase within 1.5°C.

Taking into account the long-term net-zero pledges that have been made by a number of countries, most recently by India, would limit the rise to 1.8°C in 2100 after some limited overshoot (CAT, IEA, UNEP). However, this figure should be taken sceptically, as most of these pledges are currently not backed-up by real action or planning.

Reducing the global emissions gap

Given this context, the first climate priority for 2022 should be to reducing the global emissions gap by ensuring that NDCs are enhanced to a level compatible with the 1.5°C trajectory. The Glasgow Climate Pact agreed by the 197 countries at COP26 provides a solid foundation for this.

First, the document strongly emphasises the 1.5°C goal rather than on the 2°C goal, both of which are included in the Paris Agreement. All 197 parties agree that the 1.5°C goal should be the norm, as the 2°C goal has been shown to be significantly more harmful and riskier. This development is very important. As the latest IPCC report illustrates, extreme heat events will occur roughly twice as frequently as today at 1.5°C warming levels, while at 2°C this their frequency would triple.

Second, in acknowledging the global emissions gap emerging from the current 2030 pledges, the document calls on countries to return with strengthened NDCs by the end of 2022. The European Union, the United States and the United Kingdom pushed for this earlier date because 2025, when NDCs should normally be revised again according to the Paris Agreement, is much too late to halve emissions this decade, as is required in a 1.5°C scenario.

While the Glasgow Climate Pact provides the institutional foundation to deliver on this front in 2022, delivery should not be taken for granted. Even though the Paris Agreement requires updated NDCs to be more ambitious than the previous versions at each iteration, many countries submitted the same targets as before for COP26 (eg Australia, Russia, Switzerland), while some even backtracked (eg Brazil) (CAT). And the omens for COP27 are not good: Australia and New Zealand have already said they will not adjust their NDCs, which are currently seen as inadequate. It might therefore be challenging to persuade laggards, to whom this call is addressed in the first place, to scale-up their pledges in 2022.

Two complementary actions might help incentivise countries to strengthen their 2030 climate pledges and, importantly, their climate action over the next years: international climate finance and bottom-up, sector-specific, climate deals. While failing to deliver results, Glasgow did advance the global discussion in these respective areas. Building on these advances, global climate action could bring substantial results in 2022.

Delivering on climate finance to foster action and ensure international climate justice

In general, ambitious developed countries should use 2022 to convince their peers to strengthen their climate measures if they have not done so already, including through the G7 and the G20. Much frustration was voiced over the last-minute intervention by China and India to weaken the pact on the ‘phase out’ of coal, and rightly so. China is no longer among the group of least-developed nations and is rapidly creating its own historic responsibility in terms of cumulative emissions. India does not yet bear historic responsibility and still needs help to lift its population out of poverty. However, there is simply no carbon budget to allow India to take the same polluting path as China or the West did. Instead, rich countries should scale up financial and technological support to provide credible alternatives to coal-powered development. Agreements to wean individual countries off coal, like the $8.5 billion pledge made to South Africa, can serve as a template for future commitments as they produce greater accountability for the governments involved. At the same time, individual countries should not be neglected because of a lack of multilateral funding.

The issue of climate finance is perhaps the greatest source of frustration, which is of rich countries’ own making: the failure to deliver the $100 billion per year by 2020 that was promised to developing countries during the Copenhagen summit in 2009. Depending on how ‘support’ is measured – particularly how loans are treated – the shortfall can be anything from $20 billion (as estimated by the OECD) to $80 billion per year (estimated by Oxfam, which notably argues that besides grants, only the benefit accrued from lending at below-market rates should be counted, not the full value of loans).

The Glasgow Climate Pact merely urges rich countries to deliver the same promised amount until 2025 and to at least double the financing destined for adaptation, from $20 billion in 2019. In comparison, the first dedicated UN report estimates that the NDCs of developing countries alone imply a total financing need of $5.8 to $5.9 trillion up to 2030.

Developed countries, starting with the US, should urgently make good on their promises and scale-up international climate finance. It is important to underline that several complementary options can be pursued: bilateral funding can be paralleled by multilateral funding, multilateral development banks, private sector contributions, philanthropy, Special Drawing Rights from the International Monetary Fund, and voluntary carbon markets – for which Glasgow did represent a game-changer with the adoption of rules governing the international trade in emissions reduction units after six years of haggling that had held up the Paris Agreement rulebook.

It is particularly important to flag the issue of loss and damage. This concept entered international climate negotiations in 1991, when the Alliance of Small Island States called for a mechanism that would compensate countries affected by rising sea levels. Over time, more and more vulnerable countries also realised that they are affected by climate change that is beyond their capacity to mitigate alone. The idea of a mechanism to help them address loss and damage has gained wider support over time. COP26 got very close to creating a ‘Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility’ aimed at channelling funding from rich nations to poor and climate-vulnerable countries. However, the initiative was ultimately rejected by rich countries, as they feared unlimited liability. The issue of loss and damage represents a cornerstone of international climate justice and for this reason this item will now have to be placed at the top of the 2022 climate agenda.

Fostering global climate action through bottom-up and sector-specific deals

Some of the most notable achievements at COP26 occurred outside of the Paris Agreement framework, with numerous side-deals struck by varying groups of countries. For example, some of the most forest-rich countries in the world signed up to stop deforestation by 2030, with over €16 billion in public and private funding promised to facilitate this. More than 100 countries joined the US and EU-led pledge to cut methane emissions by 30% between 2020 and 2030. Apart from the contentious ‘phasing down’ of unabated coal power which all countries signed up for, some have also committed to phasing out coal by the 2030s and 2040s or as fast as possible thereafter. A number of small producers (but some with big reserves) of oil and gas said they will stop issuing new drilling licences after 2040 or 2050. In addition, economies including China, India, the EU and the US signed a statement on the ‘Breakthrough Agenda’, declaring their goal of making clean power, zero-emission vehicles, green steel and green hydrogen globally available and competitive. Finally, in the area of private finance, the Glasgow summit saw the birth of a ‘Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero’, which could mobilise substantial resources, though the reported $130 trillion is clearly a gross overestimation.

Many of these deals suffer from softened language (eg on phasing out/down coal), disappointing precedents (deforestation) and the absence of some of the parties that matter the most: Russia, India, China and Australia did not join the Global Methane Pledge and the biggest producers and users of coal also refused to sign the coal initiative. Furthermore, the additionality of these agreements with respect to NDCs has been called into question.

Nevertheless, these sector-specific side-deals make commitments more concrete and ‘modular’. They allow countries to create their own paths towards more sustainability, which may work better given their diverse circumstances and levels of ambition. And they allow participation of other parties that will ultimately have to deliver climate action: local authorities, the private sector and civil society.

Leading countries may want to consider joining and encouraging others to do so before the next COP at the end of 2022. For example, Germany could send a signal to domestic and global car makers by joining the plan to eliminate emissions from new cars by 2040, something which is being discussed at EU level already.

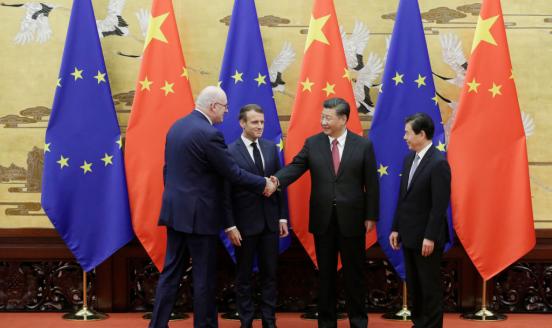

It is impossible not to mention another side-deal that galvanised attention in Glasgow: the ‘US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s’. Coming from the world’s two largest polluters – together representing 40% of global emissions – the declaration represented a breakthrough in the Glasgow negotiations. This resembled a similar agreement brokered in 2014 by the same two lead negotiators, then-Secretary of State John Kerry and China’s top climate envoy Xie Zhenhua, which paved the way for the adoption of the Paris Agreement a year later. So, while the practical impact of the declaration remains ambiguous due to its lack of concrete commitments, it represents an important political document to establish some “common-sense guardrails” on climate, in an otherwise chilly relationship of mutual mistrust.

2022: Crossing the climate bridge?

Closing the Glasgow conference, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa said that at COP26 parties built “a bridge between the admirable promises made six years ago in Paris and the concrete measures that the scientific evidence calls for and societies around the world demand”. She was right: COP26 was an important step in the fight against global warming. However, the conference failed to narrow the global emissions gap. Building on the achievements of Glasgow, the world has a real opportunity in 2022.

Rich nations have a clear responsibility in the year ahead: make good on their $100 billion climate finance commitment to support developing countries and act to protect vulnerable communities. This is the key to giving substance to the Paris Agreement’s core principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, and to ensure international climate justice.

Laggard countries, meanwhile, must revise their 2030 emissions reduction pledges and policy actions, taking into account the sector-specific deals signed in Glasgow that will hopefully be further enlarged over the following months.

It is only by promptly undertaking these actions during 2022 that countries will ultimately demonstrate that Glasgow was about real progress rather than ‘blah blah blah’.

Recommended citation:

Lenaerts, K. and S. Tagliapietra (2021) ‘Goodbye Glasgow: what’s next for global climate action?’, Bruegel Blog, 18 November