The fiscal consequences of the pandemic

The likely economic depression triggered by coronavirus will pose a serious fiscal challenge to some euro-area countries. Given the special circumstan

Countries inside and outside the EU are working hard to contain the pandemic and address its adverse economic implications. In a new dataset, we have decomposed fiscal measures announced by governments into three categories: (1) immediate stimulus, such as additional government spending and foregone revenues; (2) deferrals of certain revenue sources including taxes and social security contributions, which in principle should be paid later; and (3) other liquidity provisions and guarantees.

The magnitude and the content of fiscal measures vary widely, with the total amount of immediate stimulus ranging between 0.4% in Hungary and 5.5% in the United States. This highlights the lack of a common fiscal response, even in the euro area. It is notable that the direct additional fiscal cost of extra healthcare spending has been below 0.2% of GDP so far. Even if these amounts double or triple later in the year, the direct fiscal cost of additional healthcare measures will remain a relatively small share of GDP.

Nobody can reliably predict how deep the recession is going to be in 2020, yet many factors suggest that the economic fallout from the pandemic will be huge. The economy currently performs at 65% of its normal level in France. Italy, where all non-essential production has been halted, likely performs at a much lower level. The spread of the pandemic has not yet slowed down in many European countries and hence it is impossible to predict how long the current strict lock-down measures are likely to remain in place. Research on pandemics suggests that they have a lasting adverse economic impact, not least because people increase precautionary savings. Even if Europe compresses the pandemic in some months, the adverse impact on some industries, such as tourism, is likely to be persistent. Who would want to spend their summer holidays in Madrid, Milan or Paris, a few weeks after mass infections there? Businesses might learn that teleconferencing can replace many personal meetings, leaving a permanent negative impact on industries directly and indirectly related to travel, hotels and events.

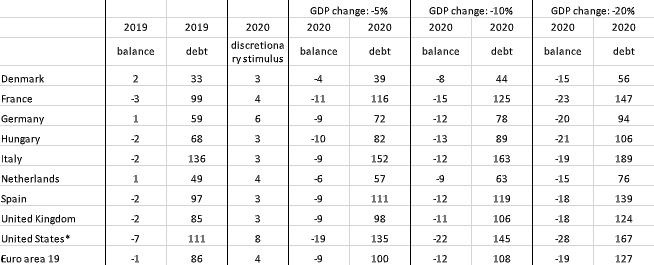

I ran simple simulations to estimate the budget deficit and public-debt implications of three alternative GDP scenarios: -5%, -10% and -20% contractions in 2020. Key assumptions:

- Slightly more immediate stimulus than what has already been adopted (in the case of countries for which, at the time of writing this blog post, we had already calculated the fiscal measures, which includes five euro-area countries, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain);

- 3% GDP immediate stimulus for euro-area countries other than France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain;

- Without the stimulus, primary (non-interest) public expenditures grow at the same rate as the average growth rate from 2014 to 2019;

- Without the stimulus, government revenues as a share of GDP are the same in 2020 as in 2019;

- Interest rate on public debt is the same in 2020 as 2019.

I do not complicate the analysis with assumptions about fiscal multipliers, that is, the impact of the stimulus on output. Instead, I assume a certain stimulus and check the implications of three alternative GDP scenarios. Also, I have not considered the deferrals (which might eventually be deferred further or even cancelled in a deep recession, increasing the budget deficit), nor the various guarantees (which might eventually be triggered in a deep recession, increasing the budget deficit). Therefore, my calculations approximate the orders of magnitude, but in a deep contraction the budget deficit and the consequent increase in the public debt/GDP ratio could be higher than what my calculations show.

Table 1: Fiscal implications of alternative GDP developments – general government balance and debt, %GDP

Source: 2019 data from the November 2019 version of AMECO, projections are Bruegel calculations.

Note: *US figures refer to federal balance and debt only, US state and local debt amounted to an additional 16% of GDP in 2017.

Countries with relatively low public debt levels in 2019 – Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany – would keep their debt ratios under 100% of GDP, even in the case of a 20% GDP contraction.

But countries with higher initial levels of debt might see alarming increases. For example, in the case of a 20% depression, which is unfortunately not unlikely, Italian public debt would reach 189% of GDP by the end of 2020. Investors, who are so far happy with the European Central Bank’s expanded quantitative easing policy, might realise that even total ECB asset purchases in 2020 would amount to less than a third of the new debt issued by euro-area countries (which I estimate at €3660 billion in 2020 if GDP contracts by 20% in all euro-area countries). New debt issuance could be even larger if tax deferrals turn out to be actual expenses and government guarantees are called on. Market pressure on high-debt countries could thus return.

True, Japan has been able to navigate reasonably well with an almost 240% public-debt to GDP ratio. But half of that has already been purchased by the Bank of Japan, and those purchases are set to continue. In the euro area, ECB asset holdings amount to 18% of the public debt of France, 26% of Germany, 16% of Italy and 22% of Spain. Continued market stabilisation by the ECB at a time when public debt explodes rapidly would require even more purchases than what has been announced so far. Large new purchases would need to be continued for several years, if not decades. Given the extraordinary circumstances caused by the pandemic, this would be desirable in my view, but might face legal challenges.

In the absence of a further massive increase in ECB purchases, some euro-area countries will likely face renewed market pressure. A key reason for this is that these countries had poor fiscal and structural policies in the past. A financial assistance programme from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is unlikely to solve the current situation, because its firepower is too small compared to the scale of the problem, plus relying on a standard bailout from the ESM would be toxic in some countries. An ESM credit line to all member states without conditionality would not do the trick either, because of its small size. The ESM’s firepower would need to be increased massively to cope with the exploding debt in some countries (Table 1).

If neither the ECB nor the ESM is able to calm markets, then a stark choice will arise: (1) allow a massive sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the pandemic crisis, which would make all EU countries worse off and might reverse the European integration process; or (2) mutualise part of the economic costs of the pandemic, for example by either a common debt-management office for the euro area, or one-off joint debt issuance, to finance common expenditures related to the coronavirus crisis (as discussed by Guntram Wolff and Grégory Claeys).

Certainly, mutualisation involves some moral hazard: EU members with high debt might not be incentivised to run responsible fiscal policies in the future, as they will learn that even if they have high debt and limited fiscal space to address shocks, others would foot the bill when a big external shock comes.

While this is a valid argument, there are important factors that call for some degree of mutualisation of the pandemic-related economic costs.

First, low-debt countries have a moral responsibility for encouraging and allowing, for example, Italy to join the euro area in 1999 when it did not meet the criteria.

Second, low-debt countries also endorsed the flawed architecture of the euro area, which is now witnessing the second dramatic crisis in a decade, without proper tools to address the crisis.

Third, some low-debt countries have benefitted massively from the single market and large current account surpluses.

Fourth, the pandemic is an extraordinary external shock causing human suffering in the epicentres which are unprecedented since the second world war.

And fifth, a massive sovereign debt crisis might risk even more human suffering and exits from the euro area, with numerous adverse consequences for many other countries too.

For these reasons, a European solution is needed, involving more ECB purchases, a significantly increased ESM and some degree of mutualisation of the pandemic-related economics costs.