The Eurosystem - Too opaque and costly?

The Eurosystem gets a lot of attention from academics and the media, but they largely focus on its statutory objective of maintaining price stability.

This blog post is based on a report that was prepared for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament (ECON) as an input for the Monetary Dialogue of 25 September 2017 between ECON and the President of the ECB.

The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurosystem face a lot of scrutiny when it comes to monetary policy, but their operational performance attracts less attention. Still, being a public institution, the ECB and the 19 National Central Banks (NCBs), which together form the Eurosystem, have to justify their methods and costs. Thus, this blog post will assess the decentralised implementation of monetary policy by the Eurosystem with particular emphasis on its transparency, operational efficiency, and simplicity. When appropriate, we compare the Eurosystem to its most similar counterpart, the Federal Reserve System (Fed) of the United States.

Transparency

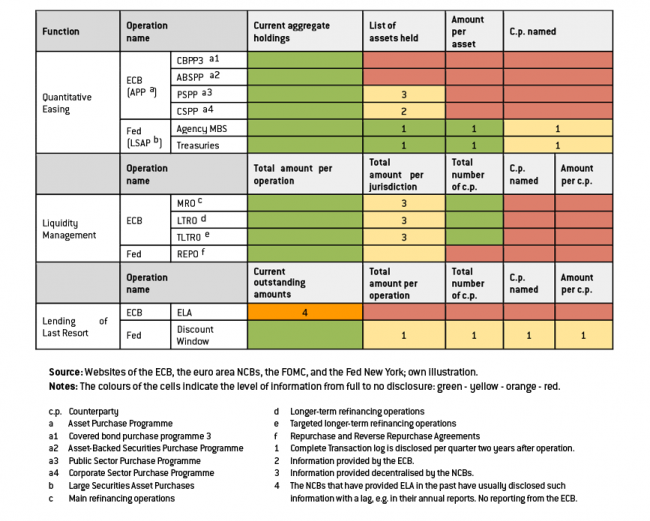

Despite some recent improvements (see Table 1), the ECB’s transparency falls behind the Fed on core monetary policies.

In fact, while the ECB discloses quite substantial (albeit yet not complete) information on its liquidity management (MRO, LTRO, TLTRO), it is much less transparent about its quantitative easing programs. In contrast to that, the Fed publishes more data about the current state of its quantitative easing programmes and even discloses a complete transaction log with a delay of two years.

The Eurosystem also provides very little information regarding its Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA). Again, the Fed is more transparent by publishing current amounts as well as historic transactions (with a 2-year delay). Table 2 provides a summary comparison between the Eurosystem’s and the Fed’s transparency in important operations.

Table 2: Information provided by the Eurosystem and the Fed for selected operations

In addition, substantial parts of the information presented by the ECB (and the NCBs) are user-unfriendly and difficult to process for further analysis.

Operational Efficiency

The term efficiency describes the amount of resources used to reach a certain goal. Unlike the case of a company, where revenues and costs can be compared, there is no straight-forward metric to assess the efficiency of a central bank. Thus, we decided to assess the Eurosystem’s operational efficiency by analysing its operational costs against its tasks.

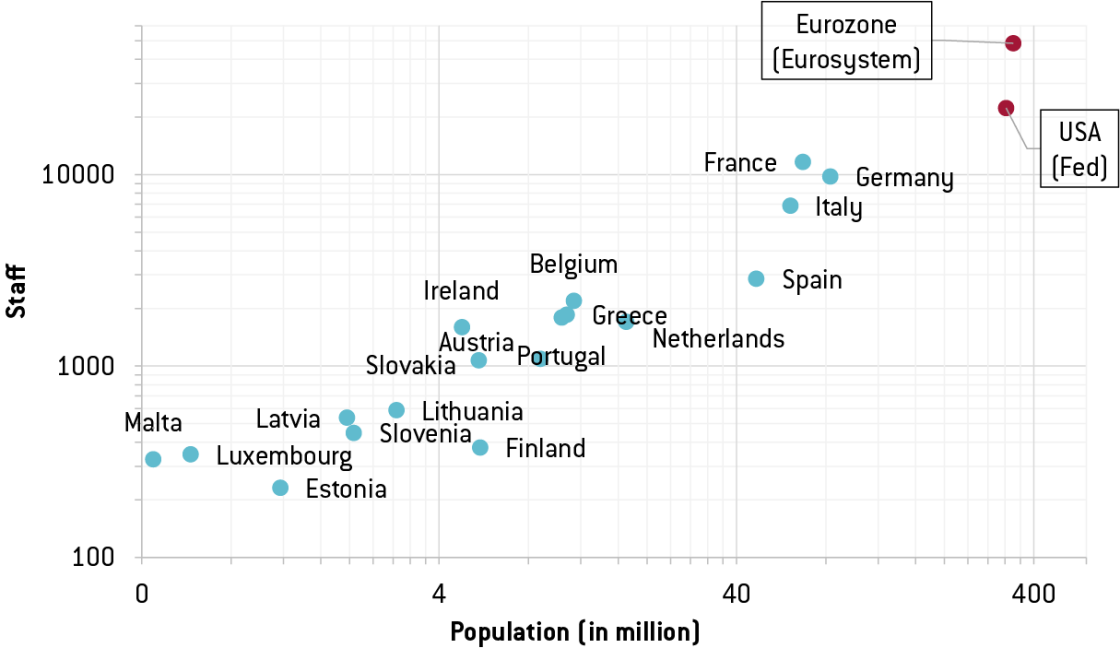

Based on figures published in the annual reports of the ECB and the 19 NCBs, we estimate that the Eurosystem has aggregate operational costs of about €10 billion, of which close to €1 billion is generated by the ECB (in 2016). The total staff size of the Eurosystem and the ECB amounts to over 48,000 and 3,100 units respectively. Compared to the Fed, the Eurosystem employs almost twice as many people (Figure 1) and has operational costs that are twice as high as those of the Fed.

Figure 1: Population and NCB headcounts (2016)

Source: ECB and NCBs’ websites; Fed Annual Report (2016); World Bank

Notes: Both axes are shown on a logarithmic scale.

Of course the Eurosystem’s and the Fed’s tasks are not totally comparable, but it is still sensible to assume that the costs of the Eurosystem are considerable higher due to its institutional structure. The Eurosystem consists of 19 NCBs and the ECB while the Fed consists of 12 Federal Reserve Banks, the Board of Governors, and the Federal Open Market Committee.

Simplicity

Based on the European treaties, the Eurosystem implements its monetary policy in a decentralised way. Compared to a centralised implementation, as seen with most central banks, the Eurosystem’s implementation is inherently more complex.

Table 3 gives an overview of which NCB is responsible for implementing which quantitative easing programme of the ECB. As depicted in the table, the set of NCBs is different depending on the programme, and no clear pattern of implementation can be deducted. On top of this, the Eurosystem does not disclose the decision rule that led to the above-mentioned scattered implementation.

The Fed has a far simpler implementation structure. All monetary policies, decided by the Federal Open Market Committee, are implemented by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Recommendations

Based on our analysis, we can identify several ways in which the ECB and Eurosystem could improve transparency and efficiency.

Regarding transparency, we suggest that the Eurosystem should take the Fed as an example and disclose more information on its monetary operations. If information contains sensitive material, we suggest releasing the information with a delay.

To increase transparency and strengthen accountability, the ECB and the eurozone NCBs could disclose full information on operational cost and staff headcounts, disaggregated by unit and function. We believe that silos between the NCBs should be broken up and that the ECB should serve as a data portal for the whole Eurosystem. Thus, we suggest that the ECB collects data about monetary operations as well as costs from all 19 NCBs and publish this data on the ECB’s website in a coherent form. If this is not feasible, we propose that the ECB should publish a common annual report of the Eurosystem that contains the most crucial information on costs and headcount of the entire Eurosystem (inspired by the Fed). We suggest that the Eurosystem publishes its reports at least in a harmonised way/design.

The operational efficiency of central banks is hard to measure, as it is not clear to which metric its cost should be compared. But our estimates, however rough, suggest that the Eurosystem is costlier than the Federal Reserve. This is not surprising as the Eurosystem is more decentralised than the Fed. Thus, we recommend bundling more (monetary) policy actions on a lower number of central banks. In addition, we suggest continuing to reduce the Eurosystem’s costs, which will imply a reduction of staff numbers, intensifying the action pursued over the last few years.

The decentralised nature of the Eurosystem, as established by the European treaties, creates a certain degree of intrinsic complexity. Therefore, a simple and centralised implantation of monetary policy would not be in line with the treaties. However, we argue that the Eurosystem could achieve more simplicity in the current treaty regime by assigning certain functions to certain NCBs in a systematic manner (specialised NCBs). In addition, we strongly suggest that the Eurosystem discloses information on its decision rules on implementation.