Europe's export superstars

What has contributed to Germany's exceptional export performance compared to other European countries?

Germany is 'Exportweltmeister' (world champion in exporting) as it is phrased by the German media. Between 2000 and 2013 German exports increased by 154 percent compared to 127 percent in Spain, 98 percent in the UK, 79 percent in France and 72 percent in Italy. In addition, no other European country saw such a quick rebound in export growth after the financial crisis in 2009 as Germany. As a result, many observers see Germany as a leading role model of successful adjustment from the 'sick man of Europe' in the 2000s to an economic powerhouse today. What has contributed to this exceptional export performance of Germany compared to other European countries?

Wage Restraint

The two leading explanations for Germany's superb export performance are wage restraint and the emergence of China. And indeed, wage bargaining among the social partners resulted in an increase in nominal wages and salaries in Germany of only 19 percent between 2000 and 2008, the lowest increase in the European Union (in Spain nominal wages increased by 48 percent during the same period).

However, since 2009 nominal wages started to rise again in Germany. From 2009 to 2013 German nominal wages increased by over 14 percent compared to 4 percent in Spain. In spite of this rapid rise in nominal wages, German exports rebounded quickly compared to other European countries. Thus, wage restraint cannot be the full answer.

The Rise of China

Has Germany benefited more from the opening up of China compared to other European countries? This indeed appears to be the case. In the five years after the financial crisis, German exports to China almost doubled, a stronger increase than in any other European country. There are two possible channels through which China may have benefited exports in European countries.

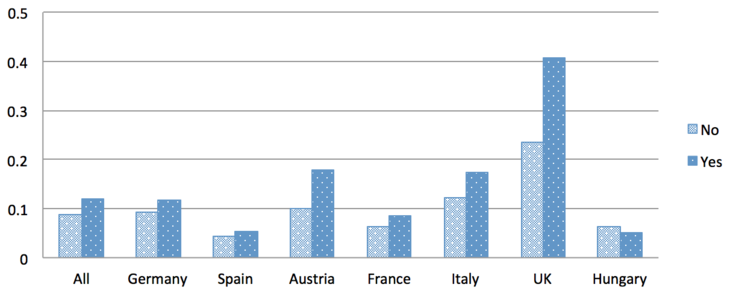

First, China may have become an important sourcing region lowering the production costs of European exporters. Our analysis of the sourcing pattern of European exporters indicates however, that the biggest gainers from sourcing in China were the UK and Austria. UK exporters, who offshored to China, almost doubled their export market share to the world, while Austria’s exporters increased their export market share by 70 percent compared to exporters, in these two countries, which did not offshore to China. In contrast, for the export market share of Spanish, German, and French exporters, sourcing from China was only marginally important. Thus, the spectacular success of German exporters appears not to be based on access to cheap inputs from the Chinese market.

Figure 1: export market share and sourcing to china

Note: Median firms’ export value/total imports of the world for the firm specific set of industries.

Second, the rapid modernization of China may have favored particularly Germany's exports with its comparative advantage in machinery, transport equipment and other manufactured goods. The data seem to support this. However, other European countries, such as France and Italy, also have a large base in transport and manufacturing goods. Therefore, the question remains: why have the Chinese such a love for German goods?

The Firm Organisation of Export Superstars

In order to get to an answer to this question we want to go deeper and examine the export business model which European firms have pursued to compete on world markets. We focus on two adjustments in firm organisation that may help exporting firms to meet competitive pressures from foreign rivals. Offshoring production to low wage countries reduce costs and allows exporting firms to compete on prices. Decentralized management provides incentives to workers for product improvements, which enables exporters to compete on quality. The idea here is that workers at lower levels of the firm hierarchy are better informed on what the market demands. Giving these workers more autonomy in decision making will provide them with incentives to adapt the product characteristics with what customers demand.[1]

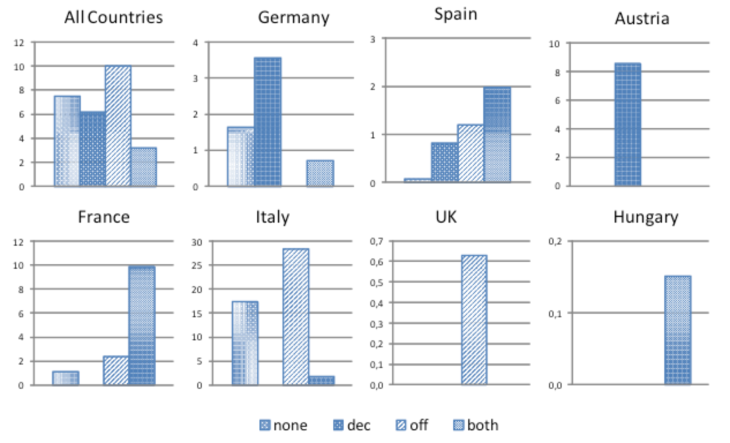

We explore the organisational responses to competition of 14.000 firms in seven European countries. The analysis is based on the EFIGE data which we merge with Bureau van Dijk’s Amadeus database in order to get detailed balance sheet and industry information. Aggregate trade data at the industry level is obtained via WITS from the UN Comtrade database. To assess the competitiveness at the firm level we construct the export market share of the export superstars in Europe, the top 1 percent of exporters in terms of export value in each country accounting between 20% and 55% of total exports in the respective country.[2] What type of organization do these firms choose to become superstars in world markets? Did these firms do significantly better when using the firm organization as a competitive tool? Figure 2 reports the answer. [3]

Germany’s export superstars more than double their export market share in the world (from 1.6% to 3.5%) when they operate with decentralized management rather than not using the organization as a competitive tool (compare the export market share of the dec-exporters with the none-exporters in Figure 2). The top 1% of exporters which abstain from any organizational adjustment (the none-exporters in the figure) do very badly in all countries except perhaps Italy. Austria’s export superstars rely exclusively on decentralized management. Italian and UK top exporters rely exclusively on offshoring (off-exporters in Figure 2), while French and Spanish exporters combine offshoring with decentralized management (both-exporters in Figure 2) to compete on world markets. From Figure 2 a distinct pattern emerges: German export superstars base their export business model on quality by relying on decentralized management. Germany shares this feature with Austria, while all other European countries base their export business model on price by offshoring production to low wage countries with or without a care for quality.

Figure 2: export market share of top 1% of exporters in percent

Notes: Export market share: Average firm's export value/total imports of the world for the firm specific set of industries. Top exporters are defined in terms of export value. none: neither decentralized nor offshoring, dec: decentralized firm, off: offshoring firm, both: decentralized and offshoring firm (categories are mutually exclusive). A firm is an offshoring firm if it has purchased inputs from abroad. A firm is a decentralized firm if managers can take strategic decisions autonomously in some business areas.

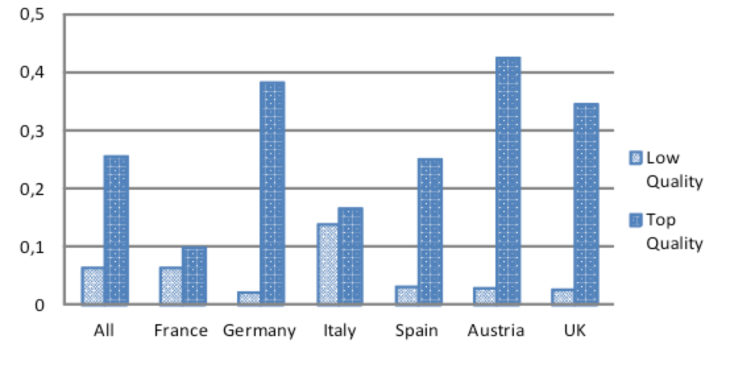

Product Quality: A subjective measure

We turn now to assess the product quality of exports across European countries. We use a subjective measure of product quality as perceived by the firms. Firms ranked the quality of their export goods relative to the market average in the range between 0 and 100. We define a good to be of top quality if it is ranked by the firms as 100. We report the results in Figure 3. Austria and Germany stand out. About 40 percent of exporters offer top quality goods relative to the market average in the respective country. In France only 10 percent of exporters have top quality goods.

Figure 3: top quality exports in percents of firms

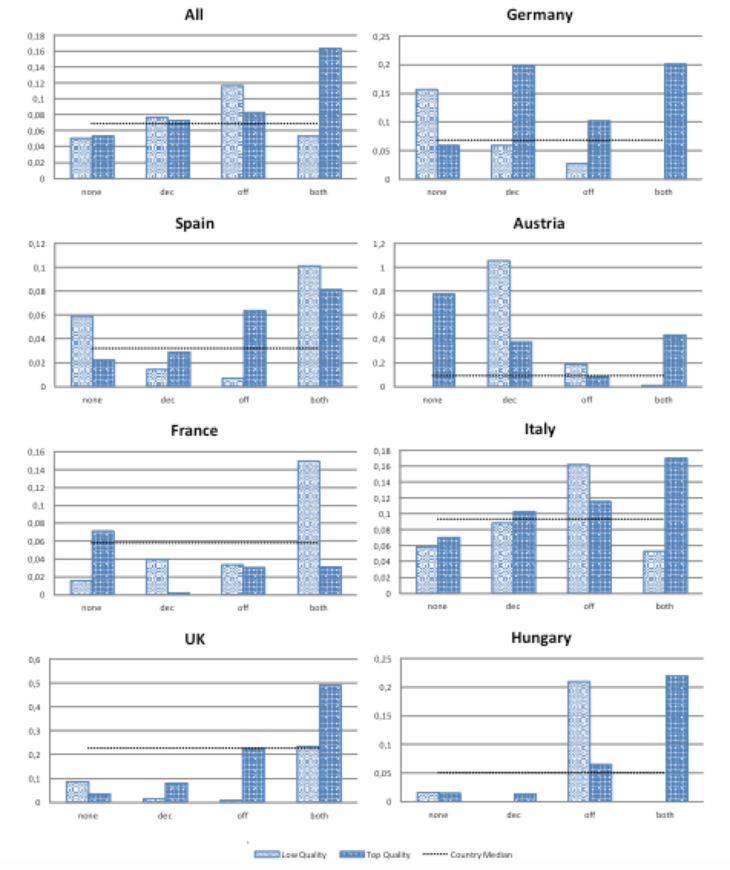

Next, we want to know whether decentralized management has, indeed, contributed to the pattern of quality across countries. This will be the case if decentralized management leads to an increase in the export market share of top quality goods. We report the results in Figure 4.

Figure 4: export market share by top quality exporters (in per mille)

none: neither decentralized nor offshoring, dec: decentralized firm, off: offshoring firm, both: decentralized and offshoring firm (categories are mutually exclusive). A firm is an offshoring firm if it has purchased inputs from abroad. A firm is a decentralized firm if managers can take strategic decisions autonomously in some business areas.

German exporters impressively demonstrate that decentralized management can provide incentives for product quality. German exporters increase their export market share of top quality goods by a factor of almost 3, from 0.07 per mille of the median exporter to 0.2 per mille when they operate with a decentralized less hierarchical organisation. Spanish and British exporters also somewhat boost their export market share of high quality goods, while Austrian and French exporters do not improve product quality when they decentralize.

Product Quality: A measure of price vulnerability

An alternative measure for product quality is the ability of firms to raise their price without losing too much of their customers to competitors. This is captured by the elasticity of substitution between different varieties of the same good. It measures the percentage decline in the demand for a Volkswagen car when e.g. Renault lowers its price by 1 percent. Presumably, Volkswagen will experience less of a decline for its cars in response to a price reduction by Renault if it is of high quality. We use this to rank the industries by the size of the elasticity of substitution as estimated by Broda, Greenfield and Weinstein (2006). We define a good to be differentiated, responding only little to price changes, if the elasticity of substitution falls in the bottom 10 percent range. We define a good to be homogenous, responding strongly to price changes, if the elasticity of substitution falls in the top 10 percent range.

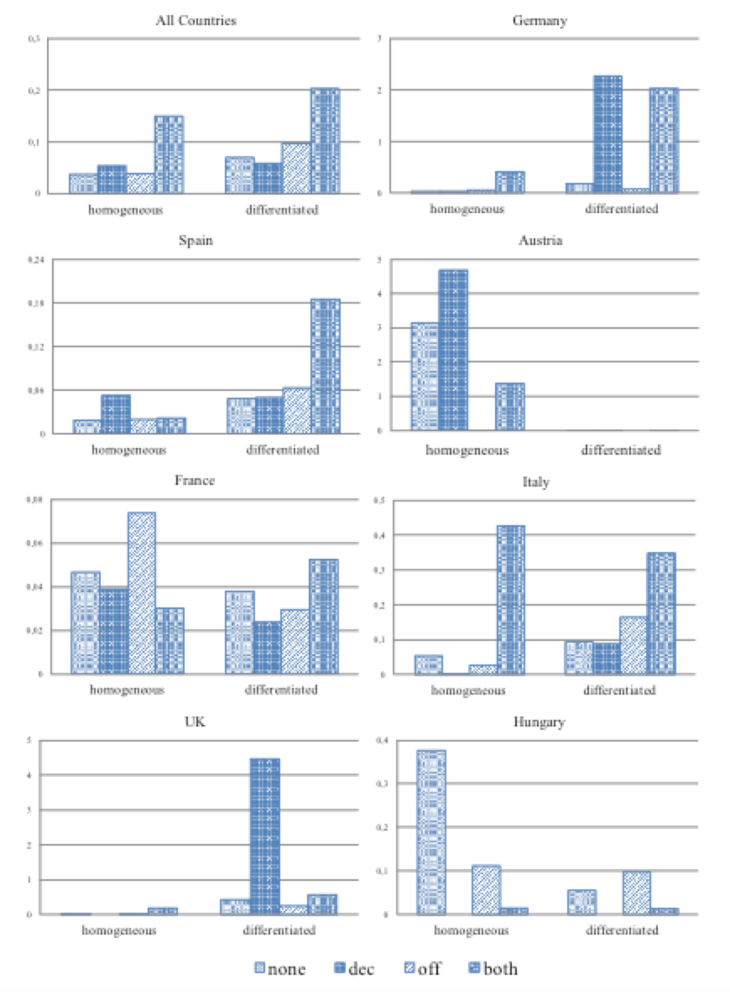

We now ask whether exporters of differentiated goods defined in this way can boost their export market share by significantly more when they operate with a decentralized organization. We report the result in Figure 5. We find that only British and German exporters boost their export market share of differentiated goods when they use decentralized management. Spanish, French and Italian exporters have to use both organizational margins to increase their exports of differentiated goods.

Figure 5: export market share of differentiated goods (in per mille)

Notes: Export market share is the median firm's export value/total imports of the world. Homogeneous goods: elasticity of substitution is in the top 10 percent range. Differentiated goods: elasticity of substitution is in the bottom 10 percent range.

Conclusion

What explains Germany’s exceptional export performance relative to other European countries? We find that Germany is a world champion in exporting because it is a world champion in organizing. The export superstars of Germany base their export business model on quality by operating with a decentralized less hierarchical organization which empowers workers at lower levels of the firm hierarchy. As a result 40 percent of German exporters sell top quality export goods. Decentralized management has been effective to increase the export market share of top quality goods in Germany which demonstrates that decentralizing the organization may actually work to improve the product quality of exporters. Austria shares many of these features with Germany, while the superstars of all other European countries base their export business model mainly on price with or without a care for quality. The focus on quality may explain why export growth in Germany and Austria rebounded quickly after 2009 in spite of rapid rising nominal wages.

References

Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, Stephen J. Redding, and Peter K. Schott (2007) 'Firms in International Trade', Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3): 105-130

Broda, Christian, Joshua Greenfield, David Weinstein (2006) 'From Groundnuts to Globalization: A Structural Estimate of Trade and Growth', NBER Working Papers 12512

Marin, Dalia (2010) 'Germany’s Super Competitiveness: A Helping Hand from Eastern Europe', VoxEU, June 20

Marin, Dalia and Thierry Verdier (2008) 'Competing in Organisations: Firm Heterogeneity and International Trade', In: Elhanan Helpman, Dalia Marin, Thierry Verdier (Eds.) (2008), The Organisation of Firms in a Global Economy, Harvard University Press.

Marin, Dalia, Thierry Verdier (2014) 'Corporate Hierarchies and International Trade: Theory and

Evidence', Journal of International Economics, 94(2): 295-310

Marin, Dalia, Jan Schymik, Jan Tscheke (2015) 'Organisations as Competitive Advantage', University of Munich, Mimeo.

Mayer, Thierry, Gianmarco I. P. Ottaviano (2007) 'The Happy Few: The Internationalisation of European firms', Blueprint Series 3, Bruegel

[1] For a model, see Marin, Schymik, Tscheke (2015). Marin and Verdier (2008, 2014) show that a more competitive trade environment leads firms to decentralize decision making to lower levels of the firm hierarchy. They find that firms decentralize in particular those decisions for which workers’ effort is most important, such as the decision over R&D and the decision to introduce a new product.

[2] It is a well-documented fact that only a few firms do all the exporting in countries, see Bernard et al (2007) for the US and Mayer and Ottaviano (2007) for Europe.

[3] We report correlations. In Marin, Schymik Tscheke (2015) we show that the causality runs from the organisation to the export market share.

For the full detailed analysis and data included in this blog read the Bruegel Working Paper Europe's export superstars - it's the organisation! from the same authors.