EU budget, Common Agricultural Policy and Regional Policy – en route to reform?

As the debate on the EU 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework gains momentum, we look at the major budget items and their effectiveness. The chall

The future of the EU budget will be a central topic for discussion at the informal European Council meeting on Friday, February 23.

Key issues are at stake: how to change the composition of spending to deliver the most European value-added, while considering new priorities? Should the revenue side of the EU budget be amended? Should EU27 countries compensate for reduced UK contributions?

On February 14, the European Commission published its contribution to the informal European Council meeting. As the Commission considers changes in EU priorities and presents a number of options about the size and composition of EU spending, in this post we look at the literature on the effectiveness of the most important EU budget items.

The 2014-2020 Multiannual Financial Framework is financed by EU Member States’ contributions and customs duties on imports from outside the EU. This money is used to carry out common European policies. Figure 1 shows the budget allocation across different policy themes.

The Structural and Cohesion Funds are used to implement the EU Regional Policy (sometimes called Cohesion Policy). Together with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), they account for 72% of EU spending, with €775 billion. “Competitiveness for growth and jobs” is the third biggest component, with €142 billion. This theme includes several well-known programmes such as Horizon 2020 (for Research & Innovation) and Erasmus+.

With €66 billion, “Global Europe” includes the EU foreign policy instruments – notably aid, neighbourhood policies and other external actions. “Security and citizenship” covers domestic issues such as health, consumption, justice and asylum – totalling €18 billion. Finally, after excluding the Common Agricultural Policy, “Sustainable Growth: Natural Resources” is allocated €11 billion, mostly for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. The Common Agricultural Policy and the Regional Policy are by far the biggest components of the EU budget. We therefore look at these in turn.

The Common Agricultural Policy has a budget of €408 billion for the period 2014-2020. This money mostly goes to the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF, 77%) and the rest goes to the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD, 23%). The EAGF is used to provide income support to agricultural producers (€294 billion expected for 2014-2020) and intervene in case of adverse shocks on agricultural markets (€18 billion expected). The underlying rationale for such a policy is that the European agricultural sector is crucial for the food supply of EU citizens. Through the “greening” and “cross-compliance” conditions on subsidies, it attempts to incentivise best practices with regards to environment and animal welfare. The EAFRD’s mission is to help rural communities develop and diversify economically, by funding regional projects.

Given the importance of this policy, its efficiency, effectiveness and fair distribution are crucial. In fact the Commission’s communication highlights that 80% of direct payments go to 20% of farmers, and calls for better targeting.

To our knowledge, no independent evaluation encompassing all aspects of the CAP has been undertaken in recent years. Nevertheless, some studies suggest inefficiencies in bettering environmental impact and biodiversity. More fundamentally, the attempted studies often point to the need to collect more data and to make CAP evaluations more systematic. A recent report by the European Court of Auditors found the CAP’s “greening” policies to likely be ineffective at improving European agriculture’s climate impact. A review of the Member States’ implementation of the CAP raises concerns about its impact. It highlights that the priorities chosen are ill-advised and the implementation is often problematic.

The Regional Policy has a budget of €367 billion for the period 2014-2020, allocated between the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF, 55%), the European Social Fund (ESF, 23%), the Cohesion Fund (20%) and, sometimes included, the Youth Employment initiative (1%). These funds are the main instruments to ensure cohesion and convergence among EU regions: alongside Member States, they co-fund economic development projects drawn up by regions. These projects must demonstrate how they contribute to progress on a broad range of objectives – from research and development activities and small- and medium-sized enterprises, to public administration and social inclusion – meant to fulfil the Europe 2020 strategy. The underlying objective of this policy is to reduce the socioeconomic disparities within the EU.

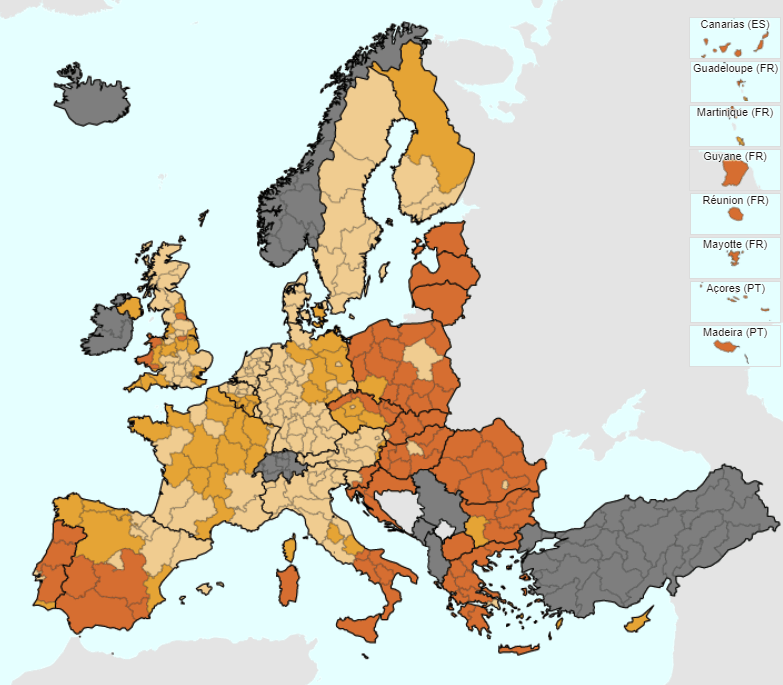

In order to stimulate convergence within the Union, the ERDF and ESF have separate budget subdivisions for different regions based on their GDP per capita. €185 billion is set aside for “less developed regions” (with GDP-per-capita [GDP/cap] of less than 75% of the EU average). “Transition regions” (with GDP/cap between 75% and 90% of the EU average) receive €36 billion. “More developed regions” (with GDP/cap above 90% of the EU average) receive €56 billion. Figure 2 shows which region is eligible for what category of funding.

Figure 2: Classification of EU regions according to development

Source: Eurostat Regions & Cities Illustrated, Bruegel, showing available data for Europe. Orange areas are “Less developed regions”, dark yellow areas are “Transition regions”, light yellow areas are “More developed regions” and grey areas are regions for which 2015 data is unavailable.

Contrary to the CAP, the Regional Policy has been subject to many independent evaluations. The growth and convergence effect of projects sponsored under the Regional Policy is generally found to be positive, but small and conditional on other regional characteristics. Importantly, it seems these funds are less effective where regional institutions and policies are already performing poorly and in socioeconomically less-developed regions. More recently, the small positive effect from Regional Policy has been found to be short-lived.

Therefore, there are major question marks about the effectiveness of both the EU’s agricultural and regional policies, none of which are addressed in the Commission’s communication.

The key challenge that EU leaders will face is in breaking the inertia in EU budgeting and to identify the spending programmes that best correspond to citizens’ objectives, and to bring European value-added in an efficient manner that member states would not be able to provide on their own.