Economy of Intangibles

Economists have been discussing the implications of the rise of the intangible economy in relation to the secular stagnation hypothesis, and looking m

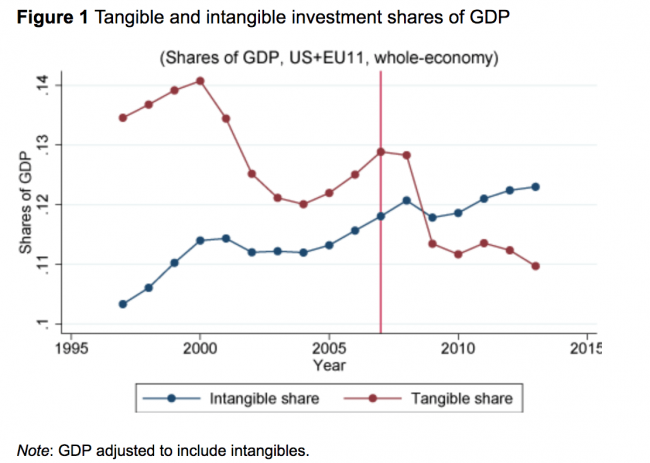

Haskel and Westlake argue that the recent rise of the intangible economy could play an important role in explaining secular stagnation. Over the past 20 years, there has been a steady rise in the importance of intangible investments relative to tangible investments: by 2013, for every £1 investment in tangible assets, the major developed countries spent £1.10 on intangible assets (Figure below). From a measurement standpoint, intangibles can be classified into three broad categories: computer related, innovative properties, and company competencies. Intangibles share four economic features: scalability, sunkenness, spillovers, and synergies. Haskel and Westlake argue that - taken together - these measurements and economic properties might help us understand secular stagnation.

The first link between intangible investment and secular stagnation is,according to Haskel and Westlake, mismeasurement. If we mismeasure investment, then measured investment, GDP, and its growth might be too low. Secondly, since intangibles tend to generate more spillovers, a slowdown in intangible capital services growth would manifest itself in the data as a slowdown in total-factor productivity (TFP) growth. Thirdly, intangible-rich firms are scaling up dramatically, contributing to the widening gap between leading and lagging firms. Fourthly, TFP growth could be slower because intangibles are somehow generating fewer spillovers than they used to.

Similar arguments have been proposed before. Caggese and Pérez-Orive argued that low interest rates can hurt capital reallocation in addition to reduce aggregate productivity and output in economies that rely strongly on intangible capital. They use a model in which productive credit-constrained firms can only borrow against the collateral value of their tangible assets and there is substantial dispersion in productivity. In a tangibles-intense economy with highly leveraged firms, low rates enable more borrowing and faster debt repayment while also reducing misallocation and increasing aggregate output. Conversely, an increase in the share of intangible capital in production reduces the borrowing capacity and increases the cash holdings of the corporate sector, which then switches from being a net borrower to a net saver. In this intangibles-intense economy, the ability of firms to purchase intangible capital using retained earnings is impaired by low interest rates because they increase the price of capital and slow down the accumulation of corporate savings. As a result, the emergence of intangible technologies, even when they replace less productive tangible ones, may be contractionary.

Kiyotaki and Zhang examine how aggregate output and income distribution interact with accumulation of intangible capital over time and across generations.. In this overlapping generation economy, the managers’ skills (intangible capital), alongside their labour, are essential for production. Furthermore, managerial skills are acquired by young workers when they are trained by old managers on the job. As training is costly, it becomes an investment in intangible capital. They show that, when young trainees face financing constraints, a small difference in initial endowment of young workers leads to a large inequality in the assignment and accumulation of intangibles. A negative shock to endowment can generate a persistent stagnation and a rise in inequality.

Doettling and Perotti argue that technological progress enhancing the productivity of skills and intangible capital can account for the long term financial trends since 1980. As creating intangibles requires a commitment to human capital rather than physical investments, firms need less external finance. As intangible capital become more productive, innovators gain a rising income share. The general equilibrium effect is a falling credit demand, consistent with falling trends in both tangible investment and interest rates. Another effect is a boost to asset valuation and rising credit demand to fund house purchases. The combination of rising house prices and increasing inequality raises household leverage and default risk. While demographics, capital flows and trade also contribute to a savings glut and changes in factor productivity, the authors believe that only a strong technological shift towards intangibles can account for all major trends, including income polarization and a reallocation of credit from productive to asset financing.

Intangibles raise questions on the policy side too. Reviewing Haskel and Westalke’s book, Martin Wolf, refering to the four features of intangible assets that the authors identify argues that, taken together, they subvert the familiar functioning of a competitive market economy, most importantly because intangible assets are mobile and thus hard to tax. This transformation of the economy demands, according to Wolf, a retxamination of public policy around five challenges: First, frameworks for protection of intellectual property are more important, but intellectual property monopolies can be costly. Second, since synergies are so important, policymakers need to consider how to encourage them. Third, financing intangibles is hard, so the financial system will need to change. Fourth, the difficulty of appropriating gains from investment in intangibles might create chronic under-investment in a market economy, and government will have to play an important role in sharing the risks. Finally, governments must also consider how to tackle the inequalities created by intangibles, one of which is the rise of super-dominant companies.

The problem is certainly relevant for Europe. Guntram Wolff has a chart showing that Germany is under-performing in intangible investments compared to its peers in France and the US and is on par with those of Italy. In a separate post, he also discusses how this relates to the mechanics of German current account surplus.

Reviewing the same book, marxist economist Michael Roberts argue that the title (“Capitalism without capital”) is inappropriate to describe the intangible economy. For Marxist theory, what matters is the exploitive relation between the owners of the means of production (whether tangible or intangible) and the producers of value ( whether manual or ‘mental’ workers). From this perspective, knowledge is produced by mental labour but this is not ultimately different from manual labour. The point according to Roberts is that discoveries, generally now made by teams of mental workers, are appropriated by capital and controlled by patents, intellectual property or similar means. Production of knowledge is then directed towards profit. Under capitalism, the rise of intangible investment is thus leading to increased inequality between capitalists, and the control of intangibles by a small number of mega companies could well be weakening the ability to find new ideas and develop them. Therefore, we have the position where the new leading sectors are increasingly investing in intangibles while investment overall falls along with productivity and profitability. This, according to Roberts, should suggest that Marx’s law of profitability is not modified but intensified.

Roger Farmer thinks that intangible investments influence company profitability. If technology companies’ profits are continually reinvested as intangibles, earnings may never appear as output in GDP statistics, but they will affect the company’s market value. For government leaders concerned with providing goods and services during a period of slow growth, getting a handle on this unmeasured GDP is essential. He thinks that we must reevaluate how tax revenue is raised. If all income were taxed at the same rate, intangible investments made by companies would still generate revenue in the form of taxes paid by the companies’ wealthy owners. The alternative – to maintain the status quo – will only ensure that as growth in the intangible economy intensifies, current revenue gaps will eventually become gaping holes.

Zia Qureshi argues that in today's increasingly knowledge-intensive economy, policies should aim to democratize innovation, thereby boosting the creation and dissemination of new ideas. This implies overhauling an intellectual-property regime that is moving in the opposite direction. Some argue that the patent system should simply be dismantled, however, that would be too radical an approach. What is really needed is a top-to-bottom reexamination of the system, with an eye to changing excessively broad or stringent protections, aligning the rules with current realities, and enabling competition to drive innovation and technological diffusion. One set of reforms to consider would focus on improving institutional processes, such as ensuring that the litigation system does not favor patent holders excessively. Other reforms concern the patents themselves and include shortening patent terms, introducing use-it-or lose-it provisions, and instituting stricter criteria that limit patents to truly meaningful inventions. The key to success may lie in replacing the “one-size-fits-all” approach of the current patent regime with a differentiated approach that may be better suited to today’s economy.