The economic debates behind COP21

What’s at stake: France will chair and host the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP21) at

Scientific consensus

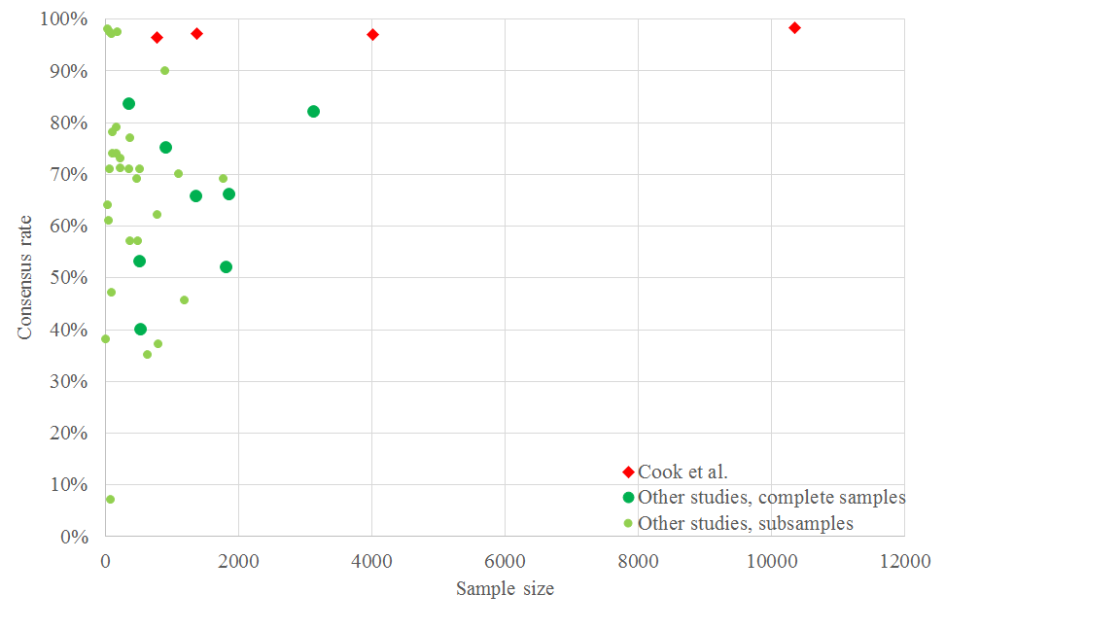

John Cook et al. examined 11 944 abstracts of peer-reviewed scientific literature published between 1991–2011 on the topics 'global climate change' or 'global warming'. Among abstracts expressing a position on anthropogenic global warming, 97.1% endorsed the consensus position that humans are causing global warming – a rare level of agreement in the world of science!

However, there is controversy about the validity of this result. Richard Tol pointed out that the paper did not meet basic academic standards, although the authors answered this criticism. The debate, more about academic rigor than about the fact that there is a consensus, is still ongoing (see here, here and Figure 1). In fact, Tol wrote:

“There is no doubt in my mind that the literature on climate change overwhelmingly supports the hypothesis that climate change is caused by humans. I have very little reason to doubt that the consensus is indeed correct.”

Figure1: Estimates of the consensus on anthropogenic global warming according to Cook et al. and other studies (Bray, Oreskes, Doran, Anderegg, Stenhouse, Verheggen) as a function of the sample size.

Source: Richard Tol blogpost.

Let us return to the political discussion. In 2009 the COP15 in Copenhagen did not result in a consensus. Parties did not adopt a successor of the Kyoto Protocol. Instead the Doha Conference (Qatar) in 2012 established a second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol (2013-2020), which concerned only a number of industrialised countries. In December in Paris, the expected outcome is a new international agreement on climate change, applicable to all, to keep global warming below 2°C.

Legal form of the agreement

Ahead of the summit, countries have agreed to publicly outline which post-2020 climate actions they intend to take under a new international agreement. Many of these stated intentions (known as Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, or INDCs) demonstrate a tendency to free riding – leading to a true tragedy of the commons. The solution, as 2009 Economic Nobel Prize Elinor Ostrom documented, always involves reciprocity and trust: "I will commit myself to follow the set of rules we have devised in all instances except dire emergencies if the rest of those affected make a similar commitment and act accordingly."

Recently US Secretary of State John Kerry announced that the Paris deal will not be legally binding treaty. François Hollande restated, as the European Commission did earlier, and as it had been agreed during the G7 summit, that those commitments should be binding. Robert Stavins and Nicholas Stern argue that those lengthy discussions on the form of a legal agreement are “futile” or “a serious mistake”, because of the extremely limited chances of political viability. (Any binding agreement would need approval from a hostile US senate, which must ratify all treaties). They argue that additional efforts should be invested in the content of the agreement instead.

Feasibility of 2°C

There are only few elements of the discussion where parties are close to a consensus. The 2°C ceiling is one of them, but according to the IEA’s recent publication, the actual pledges made by countries will be more consistent with an increase limited to around 2.7°C.

The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) is a multi-disciplinary group of scientists which provides scientific evidence on climate change to the COP officials. Oliver Geden and others argue that 2°C is essentially impossible within the IPCC’s models, as they rely on currently unproven technologies. The IPCC models that are able to hit the 2°C target rely on ‘negative emissions’ – the removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere during the second half of the century. This could probably only be achieved through carbon capture and storage technologies, which are still in their infancy.

Pricing Carbon

Carbon pricing is one of the key policies that economists call for, as effective carbon pricing is both welfare-maximising and cost-effective. The roots of the idea go back to 1920, when Arthur Cecil Pigou identified the possibility of “uncompensated or uncharged effects [due to] the consumption of things other than the one directly affected.” He advised states to encourage (or discourage accordingly) those divergences: “The most obvious forms which these encouragements and restraints may assume are, of course, those of bounties and taxes.”

Those divergences are also known in the market failure literature as externalities. What Pigou was proposing was late reframed later as a Pigouvian tax, a tax on goods that produce such externalities.

In the climate discussion, the negative externalities faced are greenhouse gas emissions. In 2006, at the initiative of Gregory Mankiw, the Pigou Club advocated higher Pigouvian taxes. It included a long list of economists, such as William Nordhaus, Paul Krugman, Ken Rogoff, Robert Samuelson and Joseph Stiglitz.

Pigou’s analysis was accepted until 1960. In his Nobel prize-winning paper “The Problem of Social Cost” Ronald Coase argued that, if the people affected by the externality and the people creating it can easily get together and bargain, taxes and subsidies may be unnecessary. In practice, as Coase himself noted, the assumption of low/near-zero transaction costs is often not satisfied and poorly defined property rights can prevent Coasian bargaining.

In the climate debate, Cap-and-Trade systems take up Coase’s ideas by providing a market to owners of carbon emission permits. To counter the major flaw in his theory regarding the problem of initial allocation of permits, recent literature advises permit auctions.

However, even if economists agree on the necessity of pricing such externalities, there is no consensus about the appropriate tools. Policymakers debate a wide range of options, but Christian Gollier and Jean Tirole say that either cap-and-trade or carbon taxes should be policymakers' preferred weapon. More political figures agree: Christine Lagarde and Jim Yong Kim made a joint statement in favour of carbon taxes, emissions-trading and the removal of inefficient subsidies.

Cost-benefit-analysis

The standard tool economists use to assess policies is cost-benefit analysis. The positive and negative consequences of a policy are estimated and added together as discounted sum - effects further in the future are assigned a lower weighting. If the benefits prevail, the policy is socially preferable.

Martin Weitzman, an economist at Harvard University, and Gernot Wagner, lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund, argue that the expected loss to society through catastrophic climate change is so large that it cannot be reliably estimated. A cost-benefit analysis cannot be applied here, as even slightly reducing a near-infinite loss is near-infinitely beneficial.

Other economists, including William Nordhaus of Yale University, have examined the technical limits of Mr Weitzman’s argument. Rheinberger and Treich argue that “as the interpretation of infinity in economic climate models is essentially a debate about how to deal with the threat of extinction, Mr Weitzman’s argument depends heavily on a judgement about the value of life”.

The second problem raised by economists is the choice in the discount rate applied when weighting future consequences in the cost-benefit analysis. How much should we value improved climate outcomes in more distant futures? In 2006 the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change was released and has been the most widely known and discussed report of its kind. However, it has often been criticised for its use of an unusually small discount rate of approximately 1.4%.

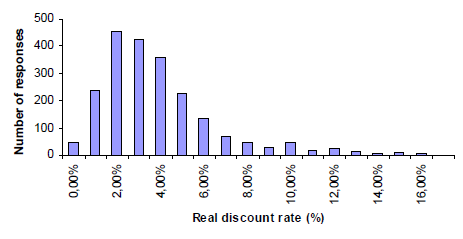

An intense debate emerged at the end of the nineties (Figure 2) about whether it is socially efficient to use a discount rate for the distant future that is different from the one used to discount cash flows occurring within the next few years. Much of this controversy is now resolved, as a 2012 all-star publication by 13 authors (Arrow, Cropper, Gollier, Groom, Heal, Newell, Nordhaus, Pindyck, Pizer, Portney, Sterner, Tol and Weitzman) converged on one mathematical formula for estimating the discount over long horizons. But the authors still hold differing opinions on how the parameters should be determined.

Those oppositions revisit a long-standing debate about the “descriptive” versus “prescriptive” approach to discounting—the former approach arguing that discount rates should reflect observed behaviour in markets, and the latter that ethical considerations should be used to set the utility rate of discount and the elasticity of marginal utility of consumption.

Figure 2: Histogram of individual estimates of the discount rate among 2160 PhD-level economists

Source: Weitzman, M.L., (1998), Gamma discounting, American Economic Review, 91, 260-271.