The decoupling of Russia: software, media and online services

Restrictions so far on software, media and online services in Russia have been imposed either voluntarily by firms, or else by Russia itself in order

Introduction

Although the United States, the European Union and many NATO-aligned nations have imposed a broad array of trade restrictions on Russia since its invasion of Ukraine, software, online services and media services are so far not explicitly subject to US or EU sanctions. Software and services trade restrictions to date are thus mainly either undertaken voluntarily by firms, or are a result of measures imposed by Russia. An exception is goods produced using US-origin software, which have been made subject to export licence requirements.

Of course, the large-scale financial sanctions put in place make it difficult for Russian firms and individuals to pay for services. This, along with the fall in the value of the ruble, makes it much less attractive for all firms, including digital services firms, to do business in Russia.

Software

A number of firms in NATO-aligned countries, including Microsoft, SAP, Amazon, Google and Apple, have announced voluntary restrictive measures on the sale or use of their software in Russia.

In normal times, software might be made available under licence, or sold outright, in which case a software maintenance contract might be offered. Alternatively, various kinds of software leases are available. Furthermore, it is increasingly common to buy software as a Service (SaaS), where the program never resides permanently on the user’s own computer.

Whatever the variant, it is likely to be easier for a software firm to voluntarily stop making new sales than to voluntarily stop servicing or providing access to already-sold software. For existing contracts, companies that fail to fulfil commitments might be vulnerable to civil suit.

However, if a firm is forced by sanctions to stop servicing the software it has already sold, it might be protected either by contractual change-of-law or force-majeure provisions, and it might also hope for compensation from the government that imposed the sanctions. How these legal niceties will play out remains to be seen, and it is unclear if Russian courts will fairly and impartially enforce contractual protections at a time when the Russia government violates international law and treaties.

Ukraine reportedly requested that the US government impose “a ban on US companies supplying and updating software in the interests of Russian consumers”. The US has not done so up to now. Such a ban might have a dramatic impact over the medium to long term on the capabilities of Russian firms and individuals, but would not necessarily have an immediate impact. It would mean software users will no longer receive security patches, which would make the software used by Russian citizens easier to hack. This could raise practical and moral questions as to whether the collateral damage that civilians would suffer is proportionate.

Software maintenance agreements typically have end-dates. Firms in NATO-aligned countries might choose to refuse to renew contracts at that time, which might protect them from legal risk. This might have substantial medium-term effect on Russian companies, but would not have instant effect.

Announcements from Microsoft appear to be in line with these observations. Microsoft has said it “will suspend all new sales of Microsoft products and services in Russia”. Already-sold Microsoft products and services are presumably not affected. Microsoft also said it was “stopping many aspects of business in Russia in compliance with governmental sanctions decisions”.

Different companies are handling the situation in different ways. Oracle has suspended all operations in Russia, while SAP has only suspended new sales; SAP continues, however, to service software already sold (to Aeroflot and Sberbank, for example). SAP justifies continued servicing of its solutions by noting that “software solutions can help organizations register refugees, coordinate volunteer efforts, and procure humanitarian goods”.

Apple stopped exports into Russia, and limited Apple Pay. On 8 March, Amazon said it was suspending access to its Prime Video service for customers based in Russia and is no longer shipping retail products to customers based in Russia or Belarus.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is by far the largest cloud services provider in the world, with an estimated market share of 33% the fourth quarter of 2021. Amazon will no longer accept new Russia and Belarus-based AWS customers. AWS presumably continues to service existing customers, at least for now. For a large enterprise, changing cloud service provider is likely to be complex and time-consuming. Amazon has emphasised that “… Amazon and AWS have no data centers, infrastructure, or offices in Russia, and we have a long-standing policy of not doing business with the Russian government”.

In retaliation against measures to block Russian access to software produced in NATO-aligned countries, Russia is considering encouraging users to ignore copyright restrictions on software. This means that the Russian government would intentionally encourage large-scale software piracy. Software often has safeguards built in against usage outside the licence terms, but it remains to be seen whether a determined Russian government might be able to bypass these.

The companies whose software would be pirated are presumably entitled to compensation for its use in violation of the terms under which the software was initially licenced, but it is unclear whether they will be able to collect under the present circumstances.

Media, social media and other online services

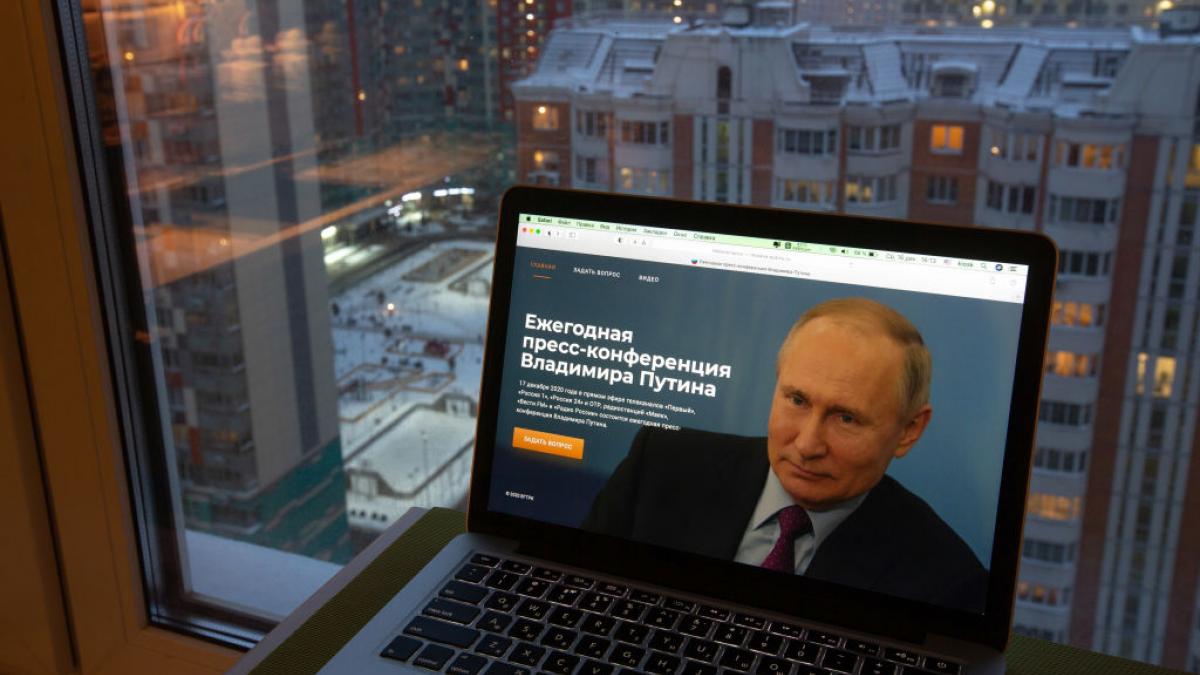

Social media and social networks do not appear to be directly subject so far to EU or US sanctions. Companies have however taken some measures voluntarily, while others have taken steps in response to a 4 March Russian law that imposes criminal penalties, including fines and jail terms of up to 15 years, for publishing purportedly false information about the ‘special military operation’.

Deutsche Welle was forced to shut down its operations in Russia weeks ago, and relocated staff and resources to Riga. Russia withdrew its accreditation in retaliation for Germany’s shutting down of access to Russian broadcasters Sputnik and RT (formerly Russia Today and considered by German security services a propaganda arm of the Russian state) because neither had applied for the necessary licences.

Media including CNN, Bloomberg and the BBC entirely stopped broadcasting or reporting from Russia; however, the BBC subsequently cautiously resumed operations. German public broadcasters ARD and ZDF paused then resumed broadcasting from Russia; however, they cover only the political, economic and social situations within Russia, leaving coverage of the war to reporters outside of Russia. Though they formally have the right to report from Russia, their reporters could face serious legal consequences under the new law imposing fines or jail time for reporting fake news about the war. The Russian censorship agency Roskomnadzor, in conjunction with Russian courts, would judge what news is fake. To call the ‘special military action’ an invasion or a war, for instance, would likely be classified as fake news.

Domestic Russian news outlets have also been impacted. Most independent television and radio broadcasters and press have been forced to suspend or cease operations. The two leading independent broadcasters, radio Echo of Moscow (Ekho Moskvy) and television channel Rain (Dozhd) have suspended operations in Russia. Some Dozhd staffers have left the country.

US social media firms have so far refrained from voluntarily shutting down in Russia. Consequently, these shutdowns were either forced by Russian authorities, or else were nominally ‘voluntary’ because otherwise the risk to staff was too great.

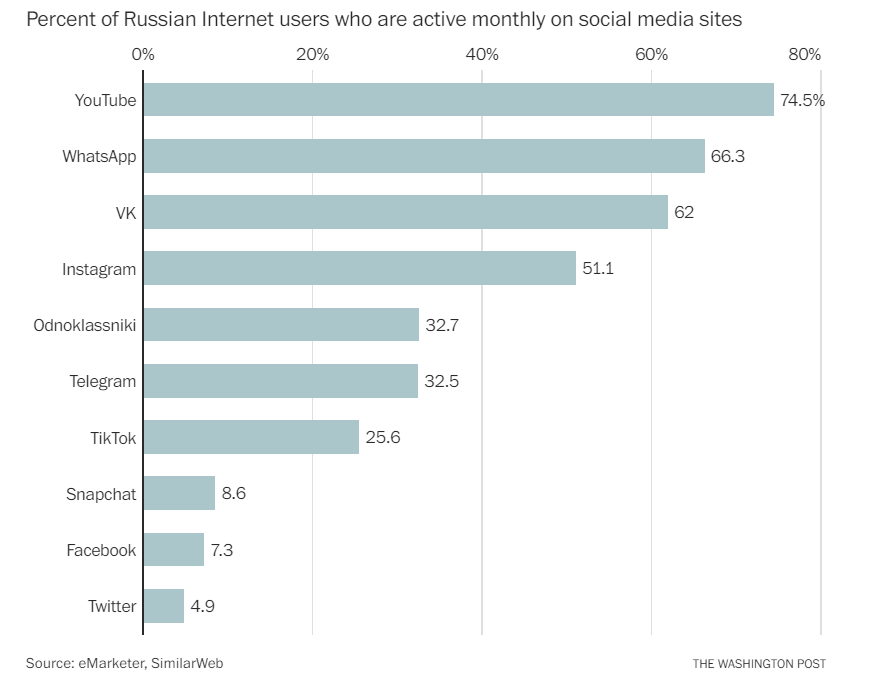

For reasons that are not yet clear, Russia initially placed restrictions only on Facebook and Twitter, even though they have a relatively small active audience in Russia compared to platforms such as YouTube, WhatsApp and Instagram (based on analysis by the Washington Post; see Figure below). Restrictions on Facebook have since been progressively intensified, and Instagram has been blocked.

Facebook was forced to stop operations in Russia on 4 March, after previously having been slowed down by technical measures. Facebook’s parent Meta noted that blocking Facebook would isolate millions of ordinary Russians from reliable information and would silence them from speaking out – Facebook would have preferred to remain open. The Russian government censorship agency Roskomnadzor announced a ban on Meta-owned Instagram on 9 March in response to Meta’s decision to permit its users to call for violence against Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian soldiers (normally prohibited by its rules) during the crisis. This shutdown had far greater visibility than that of Facebook because Instagram has a far greater number of Russian users.

Twitter’s service has been restricted but apparently not fully blocked, and Twitter has announced a new service that uses the Tor browser to bypass the Russian blockage of its service.

The impact on the Russian public of these closures of information services is presumably mixed. Russians who are urbane, young, well-educated or tech-savvy are likely finding ways to access foreign news services. Use of virtual private networks (VPNs) increased more than 10,000% in the day after Instagram was shut down. But rural, older or less well-educated Russians probably hear only the news the Russian government wants them to hear.

Netflix has decided to suspend its service in Russia. This is not an enormous impact, since the number of Netflix subscribers in Russia is thought to be about one million. As previously noted, Amazon is also suspending its Prime Video services in Russia.

Google has suspended use of its payment services in Russia, which implies that all paid Google services will continue to operate only until the period covered by the most recent payment expires. Google clarifies that they have “… paused Google ads in Russia [as well as] the vast majority of our commercial activities in Russia – including ads on our properties and networks globally for all Russian-based advertisers, new Cloud sign ups, the payments functionality for most of our services, and monetization features for YouTube viewers in Russia. We can confirm that our free services such as Search, Gmail and YouTube are still operating in Russia”.

Meanwhile, many online services that are based in NATO-aligned countries have restricted online access to Russian news / propaganda services RT and Sputnik. Apple, for instance, has disabled access to RT News and Sputnik News outside of Russia.

The policy implications for social media are complex. From the point of view of pressuring Russia economically, there might be value in general in withholding software and internet services, but it is not clear that blocking Facebook represents a real cost to the Russian economy.

But there is a substantial cost in denying Russians access to outside, unbiased information (or at least, information subject to a different bias than Russian government propaganda). On 10 March, more than 35 civil society organisations called on the Biden Administration to refrain from new measures that might limit internet access in Russia and Belarus on the basis that it would “hurt individuals attempting to organize in opposition to the war, report openly and honestly on events in Russia and Belarus, and access information about what is happening in Ukraine and beyond”.

There is thus a strong argument that the EU and US should continue to refrain from placing broad restrictions on internet services that can serve as a conduit for information into Russia.

Selective disconnection of Russia from the global internet

On 28 February, Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister Mikhailo Fedorov wrote to Göran Marby, president and CEO of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), calling for revocation of the top-level domains .ru, .рф and .su and other technical measures as sanctions on Russia. The measures would have effectively cut Russia off from the global internet, somewhat analogous to Russia’s isolation from the global SWIFT financial transaction messaging system.

Marby regretfully declined the request. ICANN is a technical body that administers internet names and numbers and does not perceive itself as having a mandate to take actions with a geopolitical basis. Aside from that, there is good reason to question whether the proposed measures would have been too broad and not necessarily effective.

One group of experts, in a 10 March position paper, provided a well-considered assessment of ways in which technical measures related to the internet might be imposed in support of sanctions on Russia. The group put forward the following principles:

- “Disconnecting the population of a country from the Internet is a disproportionate and inappropriate sanction, since it hampers their access to the very information that might lead them to withdraw support for acts of war and leaves them with access to only the information their own government chooses to furnish.

- “The effectiveness of sanctions should be evaluated relative to predefined goals. Ineffective sanctions waste effort and willpower and convey neither unity nor conviction.

- “Sanctions should be focused and precise. They should minimize the chance of unintended consequences or collateral damage. Disproportionate or over-broad sanctions risk fundamentally alienating populations.

- “Military and propaganda agencies and their information infrastructure are potential targets of sanctions.

- “The Internet, due to its transnational nature and consensus-driven multistakeholder system of governance, currently does not easily lend itself to the imposition of sanctions in national conflicts.”

The paper went on to call for the creation of a new informal body (similar to several that exist to deal with spammers and other malefactors) that would create lists of IP addresses and domain name system (DNS) that they view as legitimate targets for blocking. There would no official or government approval, but network operators and DNS resolver firms who respect the recommendations would hopefully choose to implement them. No new technical development would be required because the software mechanisms to implement this are already in place.

The group’s approach would presumably lead to Russian military and propaganda agencies being partly or fully blocked from the global internet, in much the same way that persistent spammers are already blocked. This could be done fairly quickly using existing processes and technology. Because it is based on a list of IP addresses, it could be narrowly targeted to Russian military and propaganda agencies and entities closely aligned with them (thus reducing the risk of collateral damage to the broader public), and could be quickly adapted as technical or geopolitical circumstances change.

However, the approach will be effective only if many of the firms that provide internet access and related DNS services choose to implement the proposed approach. It is much too soon to say whether this will be the case.

Meanwhile, two of the three largest international internet backbone network providers servicing Russia (Lumen and Cogent) are shutting down operations there. In both cases, these appear to be voluntary measures. Cogent’s decision appears to have been taken primarily in solidarity with the sanctions, while Lumen attributed its decision to security concerns. In both cases, they may have also been influenced by concerns that assets might be confiscated, or that staff might be subjected to criminal penalties. As with social media, and as already noted, weakening Russia’s link to the global internet would have complex impacts. Reducing the access of the Russian public to news sources from outside of Russia may be counterproductive.

Furthermore, the services offered by internet service providers are largely substitutable. As long as there is sufficient overall capacity, decisions by internet service providers to pause or stop providing services might not have much impact on firms or individuals that currently receive services from the companies in question.

Conclusions

The decoupling of Russia from online services, software and online and offline media is already well advanced. But these are not conventional sanctions. Most of the decoupling to date has been the result either of voluntary actions taken by firms based in NATO-aligned countries, or else has been initiated by the Russian government to limit the information available to its own citizens.

Measures related to software, online and offline media, and other online digital platforms, do not function in isolation. Their effect is best understood as synergistic to the many large-scale financial restrictions that have been put in place.

It is difficult to target such digital restrictions narrowly enough to ensure that they hurt only activities that the Russian government’s opponents want to hurt, and do not cause unintended or disproportionate collateral damage.

The decision of many US-based firms to stop selling software probably has more symbolic effect than immediate practical effect, since in most cases the software that has already been sold will continue to operate for some time.

The direct economic impact of the various trade restrictions on online and offline media and on other digital online platforms is uncertain so far, but their visibility to the Russian public is likely considerable. The abrupt disappearance of familiar online services, including widely-used Instagram services, will surely be felt.

The events of the past few weeks have made clear that digital online platforms that deliver news have played a crucial role in making well-informed segments of the Russian public aware of the war. The Russian government has taken steps to censor news and the digital platforms that disseminate it precisely because such platforms are an effective communication channel. This strongly suggests that NATO-aligned countries should prioritise keeping these channels open, as much as possible and for as long as possible, while other sanctions on the Russian economy take their toll.

Recommended citation:

Marcus, J.S., Poitiers, N. and P. Weil (2022) ‘The decoupling of Russia: software, media and online services’ Bruegel Blog, 22 March