Cross-border telework in the EU: fab or fad?

Europe should investigate the possibility of ‘digital frontier worker’ status for cross-border remote workers.

Before COVID-19, the incidence of structural telework in the European Union was flat, at around 3% of all employees. In 2020, the rate jumped to 11% because of social-distancing measures. This shock is expected to have lingering effects as workers now demand more flexible working conditions, including the possibility to telework. This change is also taking place on the labour demand side, with employers increasingly advertising remote work possibilities.

Remote job vacancies could potentially be filled by job seekers from any country, but there is currently little evidence on cross-border remote work. Internations, an expat networking platform with 4.5 million members in 166 countries, reports that nearly four in five expats could work remotely in 2021. On the other hand, traditional (non-remote) cross-border work was done by 1.5 million Europeans in 2019. While traditional cross-border work accounts for less than 1% of EU employment, the potential for remote cross-border work is much greater.

Is telework here to stay?

To investigate the amount of telework offered by employers, we explored online vacancy data collected by Burning Glass Technology (BGT), which is a useful source of information about current labour market demand, especially for high-skill occupations – in principle the most ‘teleworkable’ occupations. The BGT dataset contains information about occupation, industry and region of the advertised job, details of skills required, and the full job posting text.

To analyse the vacancy text using English-language models, we selected job ads from Ireland. After removing duplicates, almost 975,000 job postings were left for the period 2018-2021. For methodological details, see the annex.

We found an increase in job ads that mentioned remote work both in the positive sense – jobs that allow telework – and in the negative sense – jobs which do not allow telework. Remote job ads increased from 0.6% of all ads in 2018 to 3.5% in 2020 and 6.2% in 2021 (these remote job ads do not indicate the proportion of actual telework). The share of jobs ads mentioning that remote work is not possible also increased from 0.1% to 0.4% during the pandemic (Figure 1).

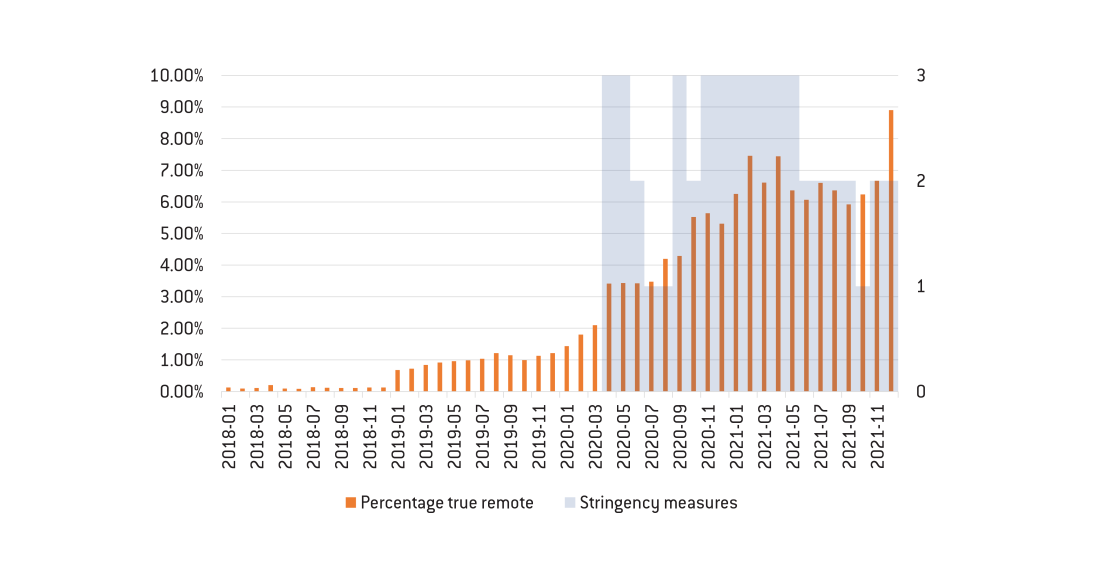

To investigate whether remote work is a temporary phenomenon only, induced by social-distancing measures, we linked the monthly variation in remote work ads with data on work-from-home stringency measures imposed by the Irish government. Oxford University’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker documents a wide range of measures introduced in response to the pandemic. We picked the indicator that tracks work-from-home stringency measures, ranging between 1 and 3, with 3 being the most stringent. Figure 2 shows that remote work offerings and stringency measures seem related to some extent, but do not follow each other closely. In Ireland, stringent measures were introduced in April 2020. Remote work vacancies then gradually increased in the following months. The highest levels of remote work vacancies were seen in winter 2021, when work-from-home measures were at their most stringent. However, remote work continued to be offered even when measures were eased later in 2021.

Figure 2: Job ads offering remote work (indexed to January 2018[SG1] ) and stringency of work-from-home measures

Source: Bruegel.

The potential for telework from the perspective of completion of tasks was already evident before the pandemic, but actual uptake of telework was far below the technical ‘teleworkability’ (or possibility to provide labour input remotely) for each occupational group. Before the pandemic, telework was mostly taken up by professionals and managers. While clerical support jobs – and technician jobs to a lesser extent – were also highly teleworkable, their telework uptake was considerably lower than in managerial and professional jobs (Figure 3, panel A), pointing to a bias induced by the occupational hierarchy.

The Irish online vacancy data shows an increasing trend in vacancies allowing telework for most occupations (Figure 3, panel B). The increase in telework vacancies is most striking for professionals, who were already teleworking the most in 2019. However, vacancies for clerical support workers also showed a marked increase, indicating convergence towards the level of technical teleworkability for these jobs.

To conclude, there is evidence that remote work continues to be offered by employers, even after the relaxation of lock-down measures. This trend can be seen for a wide range of occupations that are – at least to some extent – technically teleworkable, including managers, professionals, technicians, clerical support workers and even service and sales workers.

Benefits of cross-border remote work

The pandemic shock led employers and employees to set aside any resistance to telework and converge on a new, mutually beneficial cooperative equilibrium. Cross-border remote work, when the employee resides in a different EU country to the employer, could offer further benefits.

Let us take the example of Carlota, a recent university graduate living in Andalusia, Spain. Though she has the right skills and knowledge, she struggles to find employment in her region because of a lack of opportunities and fierce competition. By working remotely cross-border, she would be able to stay with her friends and family in Andalusia while working for an employer located in the Netherlands. Similarly, an employee located in the Netherlands might prefer to perform their work remotely from Spain rather than from the Netherlands, because of the better weather and lower cost of living.

Meanwhile, employers that employ cross-border remote workers have a larger labour market to recruit from, which is particularly relevant today when many experience labour shortages. For example, many firms find it difficult to recruit software professionals, an occupation that is highly teleworkable.

Finally, economic value is created across two countries when legal frictions that limit labour mobility are removed. As teleworkable jobs are on average paid more[1], in our example Carlota would create spillovers from her high-skill consumption to the low-skill labour markets of her home region, for example by the groceries she buys, the restaurants she eats at, and the household work she pays for.

Obstacles and a potential solution for cross-border remote working

Since remote work is here to stay and cross-border remote work could improve welfare generally, a supportive legal framework for people with traditional employment contracts[2] is required to remove barriers.

There is no specific legal status for employees who work remotely from a different EU country. In EU law, they would be considered posted workers, multinational workers or a normal employee in their country of residence (when their employer is deemed to have a permanent establishment there). Their status is largely dependent on the number of days spent in that country, together with the nature of the work they do there. This status is important as it affects the employee’s social security, personal income tax and applicable labour law; the employer’s taxes; and the country’s budget.

Because of the lack of a specific legal status and the associated uncertainty, there is currently no to very little cross-border remote work being done by employees (self-employed workers have more freedom to work remotely across borders, but lack employee benefits)[3]. A great example of the uncertainty an employer faces is the risk to be legally deemed to have a permanent establishment in the country of the remote worker. It is less dependent on the time the employee spends abroad, but more on the nature of the activities performed, the industry, the country and specifically whether the employee habitually exercises the authority to conclude contracts in the name of the enterprise. The calculation of the consequent corporate tax bill provides a headache for employers (especially for smaller companies without access to legal counsel), as the calculation of the value created by that employee is often ambiguous.

Although there is no specific legal status for remote cross-border work, there is a status for employees who cross a national border physically from their country of residence to the country where they are employed within the EU, ie frontier workers or cross-border workers. Since cross-border remote workers also live in a different country to their state of employment, but cross the border digitally instead of physically, Europe could consider introducing the concept of a digital frontier worker. In fact, during the pandemic, cross-border workers effectively became digital frontier workers when lockdowns obliged them to telework. However, during the pandemic a force majeure was declared, suspending the changes that would normally have to take place in tax and labour law, amongst others. Now, cross-border workers might still engage in some telework even though restrictions have been lifted. Consequently, they and their employers are exactly exposed to the aforementioned difficulties.

Table 1 gives an overview of the issues that need to be considered for Carlota and her employer under three work regimes: a current remote work employment arrangement, traditional cross-border worker (or frontier worker) status, and our proposed digital frontier worker status (note there is no evidence of a considerable number of remote employees under the current regime; column 1).

An explicit legal framework under the digital frontier worker concept reduces uncertainty. Additionally, it is less dependent on thresholds that trigger the application of different work statuses which subsequently creates legal and tax implications for employers and employees. It is important to note that countries only have bilateral treaties on cross-border work with neighbouring states. Cross-border telework is not limited to neighbouring countries and could potentially lead to 27 x 26 bilateral deals. While this is a strong argument for a common EU rule, the EU could also act as a facilitator in the negotiations between non-neighbouring EU countries, by setting common principles. This would help distribute the economic value created by the remote-work employment contract in a fair and equitable way.

[2] Not to be confused with ‘digital nomads’, who are typically self-employed and can more easily move between countries.

We thank Mario Mariniello for valuable input to earlier versions of this work, and Michal Krystyanczuk for the text analysis.

Annex: Sentiment analysis for identifying remote work opportunities

Job ads provide useful information about job offerings, but given their unstructured nature, this information needs to be extracted using text and sentiment analysis. In a first step, we defined a list of key words associated with telework based on Google Trends. Google Trends collects all search queries related to a specific concept in one topic. In our case, we collected the queries related to ‘remote work’ that were googled in Ireland in the past five years. This list of ‘telework-related words’ was used to scan the text of the Irish job postings over the past four years. A basic count of these key words in the vacancy texts shows an increasing trend in the prevalence of telework-related words in job offerings.

Some of the key words, however, appear to be used in a negative sense, for instance: “remote work is not possible”. To exclude these vacancies from our count as remote offerings, we used a predefined machine learning model, so-called zero shot classification models. This class of model belongs in the category of unsupervised learning models which can predict the topic of a text without labelling samples. Our model, Bart large model for NLI-based Zero Shot Text Classification, has 90% accuracy.

Working with big data requires high computing power, so we necessarily limited the sentiment analysis to the job offers explicitly mentioning words associated with telework. Removing duplicates and missing values for occupations left us with a sample of about 38,540 observations on which to perform the sentiment analysis.