COVID-19: The self-employed are hardest hit and least supported

Self-employed workers are hardest-hit by COVID-19 lockdowns. Yet they often receive less government support than salaried employees. Is the disparity

Government support packages to help workers endure the disruptions caused by COVID-19 are ostensibly generous but often discriminatory. In many countries, self-employed workers receive less support than salaried employees. In the Netherlands, for example, a worker who usually earns €3,000/month receives €1,200 less in COVID-19 support if she is self-employed. Are there good reasons for this unequal assistance?

Self-employed workers are hardest-hit by COVID-19

The self-employed represent 14% of the EU workforce (Eurostat, 2018). They work disproportionately in the sectors hardest-hit by the lockdown: 44% of self-employed workers versus 37% of employees (Figure 1).

The uneven distribution shown by Figure 1 is particularly worrying because most self-employed workers are financially worse off than employees. The median self-employed worker earns 18% less than the median employee (equivalised net disposable income, Eurostat 2018)[1].

A significant share of the self-employed is at the extreme end of financial fragility, though some self-employed workers command very high earnings. In the language of economists, the self-employed are over-represented in both the upper tail and the lower tail of the income distribution (Schneck 2018, Astebro et al 2011, and IFS). A quarter of all self-employed workers in Europe are in situations characterised by economic dependence, low levels of autonomy and financial vulnerability (Eurofound, 2017)[2]. European self-employed workers are twice as likely as employees to suffer from poverty and social exclusion[3] – social ills that threaten over a quarter of the self-employed in some countries (Eurostat 2018, Eurofound 2017)[4].

Gaps in social protection coverage add to the financial vulnerability. Self-employed workers are especially exposed to sudden drops in earnings. In eight EU countries, including Belgium, France and Italy, the self-employed are barred from one or more of the insurance-based schemes that are mandatory for salaried employees (European Commission, 2017). In these countries, self-employed workers are excluded from certain social insurance programmes, such as sickness, unemployment and/or occupational injury.[5]

Even in countries where the self-employed can access social insurance programmes, they might be under-protected in practice (European Commission, 2017). Eligibility conditions and income assessments can be such that self-employed workers receive lower benefits and for shorter periods than employees[6].

Measures adopted to support self-employed workers

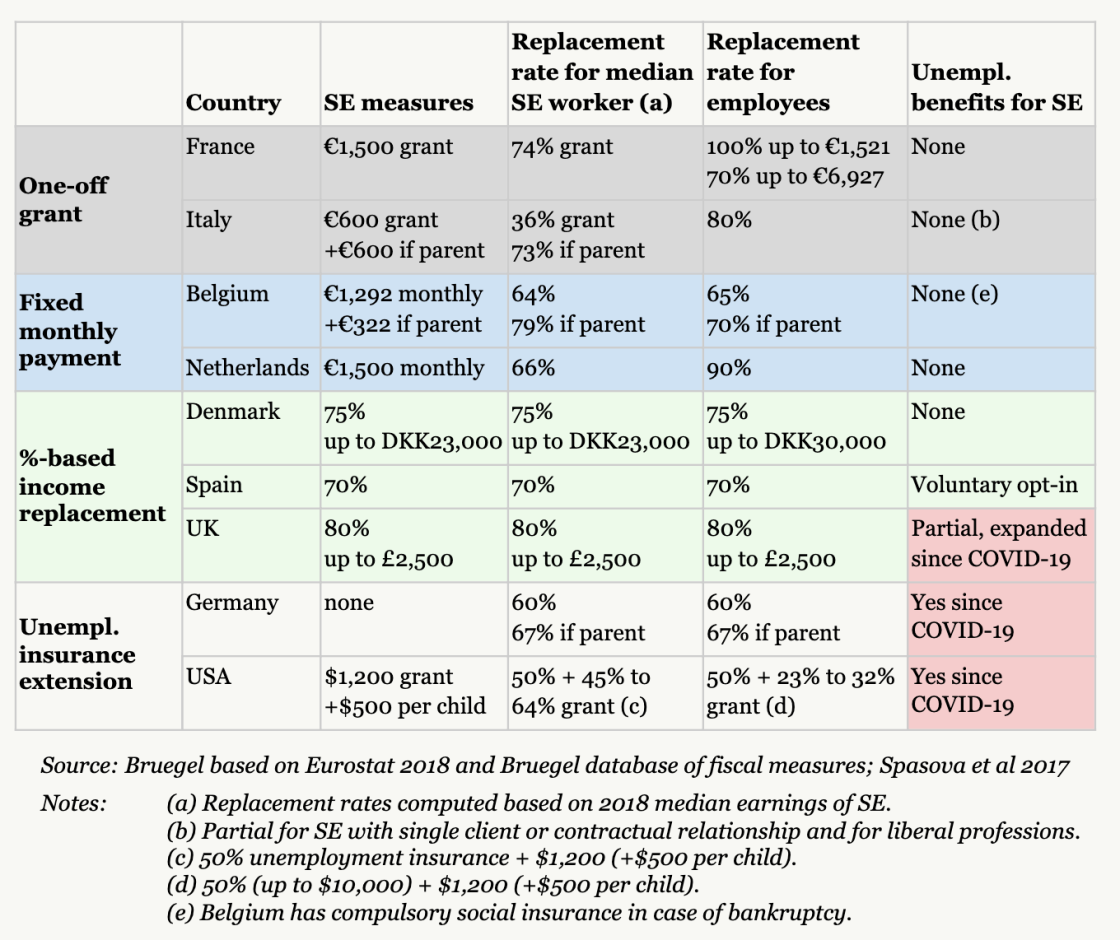

In Europe and elsewhere, fiscal measures have been rolled-out quickly to support the self-employed through the COVID-19 epidemic. Table 1 shows the measures adopted in seven EU countries, the United Kingdom and the United States. The analysis focuses on measures aimed at replacing the lost earnings of individuals. It does not include measures to protect small businesses from bankruptcy (eg liquidity injections through grants or government-guaranteed loans). The analysis also excludes programmes that support individuals regardless of employment status, such as food and housing subsidies.

Table 1 shows the various measures as income replacement rates, as a means to compare the support for median self-employed workers and employees. Income replacement rates are out-of-work income received as a share of in-work income.

Table 1: Income support schemes for self-employed (SE) workers and employees affected by the COVID-19 crisis

Four types of income-support scheme emerge from Table 1: one-off grants (in grey in Table 1), fixed monthly payments (in blue), percentage-based income replacement schemes (in green), and unemployment benefit programmes extended to self-employed workers (in red).

Comparing the measures

Are employees and the self-employed getting the same deal? This question can be answered in relation to administrative costs, frequency of payments and replacement rates.

In all of the European countries under study, businesses and self-employed workers must prove that their earnings have been negatively affected by the coronavirus to access rescue funds.[7] This requirement entails administrative costs. While these are borne by employers in the case of salaried workers, self-employed workers must expend their own time and resources and are thus disadvantaged.

In terms of frequency, recurring payments are clearly preferable to one-off grants. One-off payments do little to reduce the uncertainty that plagues households in times of crisis: will it be possible to make ongoing payments? Yet, in France and Italy, self-employed workers have been offered one-off grants, while employees receive monthly support. This puts self-employed workers under much more severe stress than their salaried counterparts.

Finally, when it comes to replacement rates, most self-employed workers get an equal or worse deal than employees. Two groups of countries emerge.

The first group includes all countries that adopted percentage-based income replacement schemes or extended unemployment insurance (in green and red in Table 1). In these countries, replacement rates are the same for the employed and self-employed (eg in Spain, all workers receive 70% of their monthly income).

The second group includes the countries that offer one-off grants and those that provide fixed monthly payments (in grey and blue in Table 1). Income replacement schemes in this group are distributionally blind: self-employed workers receive the same fixed sum whether they usually earn €1,200 or €3,000. Those earning higher incomes are therefore disadvantaged compared to employees in the same income bracket. In the Netherlands for example, a discharged dancer who typically earns €3,000 will receive €2,700 this March if she is salaried, but only €1,500 if she is self-employed. Conversely, those in the lower income bracket get a better deal if they are self-employed (eg self-employed workers earning less than €1,667 in the Netherlands).

Table 2: Summary comparison of income support schemes for self-employed workers and employees affected by the COVID-19 crisis (a)

In most countries, therefore, employees and the self-employed are receiving unequal support (Table 2). Is it simply fiscally and politically impossible to level the playing field — fairness might involve higher taxes or lower replacement rates for salaried workers, who represent the majority of the electorate — or are there good reasons for this unequal assistance?

There are plausible arguments in favour of smaller bail-outs for the self-employed – arguments related to moral hazard, unequal tax contributions and all of the reasons advanced to justify excluding self-employed workers from social unemployment insurance. On moral hazard, for instance, it could be argued that self-employed workers should assume the downside risks of their activity, since they knowingly forgo financial security for the sake of flexibility and autonomy.

In this crisis however, one argument overrides all others: lockdowns are adopted for the health and safety of every individual, therefore the economic burden should fall equally on all. If my Uber driver gets sick, I get sick. Political platitudes aside, we really are ‘all in this together’. Therefore the self-employed must be entitled to equal assistance to withstand the lockdown.

Pragmatically, equal assistance means offering recurring monthly payments and income-replacement rates that account for the social-insurance gaps and higher administrative costs faced by the self-employed. But how will countries pay for the additional spending? The EU may be coming to the rescue: the Commission recently proposed a scheme that would, if adopted, help EU countries cover the costs of income replacement programmes (the so-called SURE instrument).

However funded, countries should view expenditures directed to the self-employed as an investment, not lost resources. When the crisis eases, a flexible workforce will be a great asset. A battered one will not.

References

Adam S., Miller H., Waters T. and Xu X. (2020) ‘Support for the self-employed during the coronavirus pandemic’, IFS Briefing Note BN274, IFS, available at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/Support-for-the-self-employed-during-Cov…

Åstebro, T., Chen, J. and Thompson, P. (2011) 'Stars and misfits: Self-employment and labor market frictions', Management Science, 57(11): 1999-2017

Schneck, S. (2018) ‘The Effect of Self-Employment on Income Inequality’, GLO Discussion Paper No. 281, Global Labor Organization (GLO)

Spasova, S., Bouget, D., Ghailani, D. and Vanhercke, B. (2017) 'Access to social protection for people working on non-standard contracts and as self-employed in Europe', A study of national policies, European Social Policy Network (ESPN)

Vermeylen, G., Wilkens, M., Biletta, I. and Fromm, A. (2017) ‘Exploring self-employment in the European Union’, Publications Office of the European Union

[1] Median equivalised net income: the median of total income of all households, after tax and other deductions, that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equivalised adults; household members are equalised or made equivalent by weighting each according to their age, using the so-called modified OECD equivalence scale. The average self-employed worker earns 7% less.

[2] Self-employed workers labelled as either ‘vulnerable’ or ‘concealed’.

[3] Eurostat 2018 “People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by most frequent activity status (population aged 18 and over)”

[4] These countries are Estonia, Luxembourg, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Spain.

[5] The full list of countries is: Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, France, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia. Note that Belgium provides compulsory social insurance to cover cases of bankruptcy, the amount of which may be higher than the unemployment benefit paid to former salaried workers.

[6] Such is the case, for example, in Denmark, Estonia, Greece, and Finland for unemployment benefits, and Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, and Slovenia for sickness benefits.

[7] Though the administrative burden varies greatly across jurisdictions. See https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/03/world/europe/coronavirus-Berlin-self-employed.html