Corruptionomics in Italy

Tackling corruption is not only a matter of fairness, but it is also crucial to boost Italy’s potential output after three years of recession and almo

In line with its National Reform Programme for the period 2015-16, Matteo Renzi’s government obtained parliament’s approval on a new anti-corruption law on May 21. We document the sheer size of corruption in Italy and argue that tackling it is not only a matter of fairness, but also crucial to boost the country’s potential output after three years of recession and almost two decades of stagnation. Experience from past success cases suggests that only forceful and comprehensive actions will succeed in bringing corruption under control.

The problem of corruption[1] in Italy is real and large. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, the most widely used indicator of corruption, shows how Italy occupies the last place in Europe and 69th in the world, on par with Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece. This picture is confirmed by other organisations. The World Bank’s indicator for Control of Corruption ranks Italy 95th out of 215 countries, again neck and neck with Greece, Romania, and Bulgaria. The WEF ranks Italy 102nd out of 144 countries on indicators related to ethics and corruption.

The economic consequences of corruption can be dissected in two classes: static and dynamic. Statically, corruption leads to the creation of deadweight losses, as it drives prices above their marginal cost of production. This implies a loss for both the public (e.g. in the form of investment projects being more expensive) and the private sector (e.g. in a bureaucratic procedure costing more to execute). The Italian Court of Auditors estimates these direct costs of corruption to be in the order of magnitude of €60bn per year, equivalent to roughly 4% of the country’s GDP.

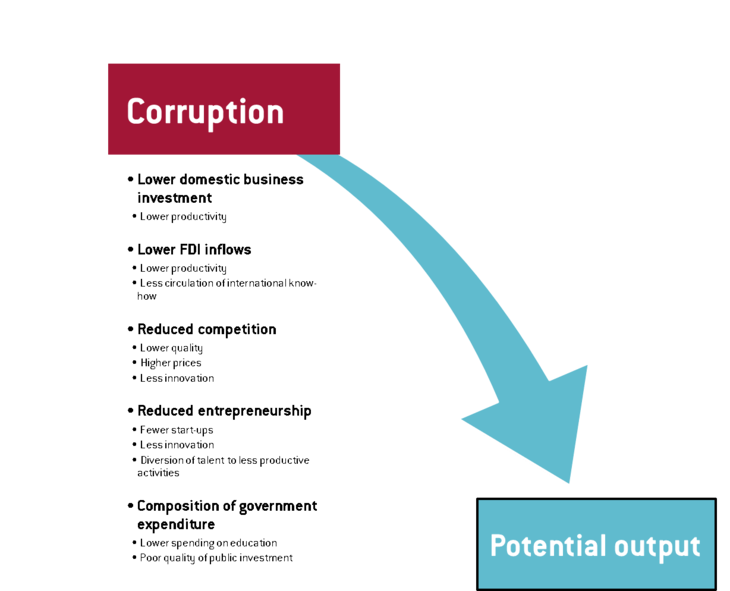

However, dynamically, corruption also distorts economic incentives and, in turn, weighs on potential output. The literature has identified several channels through which corruption affects a country’s medium- and long-term growth potential. The most relevant ones for an advanced economy like Italy are:

1. Domestic investment: Corruption not only reduces investment profitability, but also generates uncertainty in the returns to investment. This in turn will affect a country’s total factor productivity and potential output. Empirically, Mauro (1996), Dreher and Herzfeld (2005), Pellegrini and Gerlach (2004), only to mention a few, test this channel and all find a statistically significant negative effect of corruption (however measured) on investment.

2. Foreign Direct Investment: for the same reasons mentioned in point 1, corruption also directly reduces inward FDI, as argued by OECD (2013a). This is particularly problematic as the latter is associated with the international transfer of technology and management know-how, and hence the rate of technical progress – all crucial contributors to long-term growth.

3. Competition: Corruption can weaken antitrust enforcement, create barriers to new entry, or generate other barriers that preserve the privileges of established firms, as documented by OECD (2010). Weaker competition will affect productivity growth and innovation, as spelled out in Mariniello et al (2015).

4. Entrepreneurship: As rewards from entrepreneurial activity shrink, potential entrepreneurial talents might be diverted to alternative carriers in rent-seeking activities, as argued by Murphy et al (1999). The result will be less entrepreneurs, less start-ups, less innovation, and ultimately, lower growth. The validity of this channel in developed economies was recently tested and confirmed by Avnimelech et al (2011) by using a unique LinkedIn-based dataset.

5. Quality of government expenditure: Corruption will impact the level and composition of government expenditure. Firstly, it will increase the cost of goods and services purchased by the public sector, reducing the funds available for productive government use. Secondly, it will affect the composition of expenditure, as resources will be diverted to headings where corruption can be more easily concealed (see IMF, 1998).

Figure 1. Transmission channels of corruption on potential output

Source: Bruegel

And indeed the symptoms summarised in Figure 1 are all there. Although these might be individually due also to other factors, their joint reading seems to suggest that corruption might be weighing on long-term growth precisely through the channels identified by the literature.

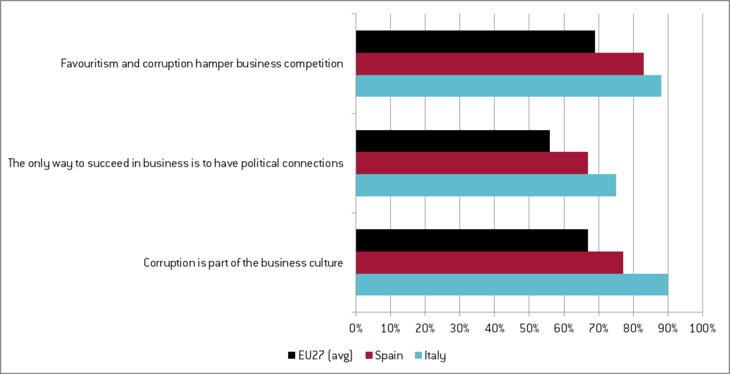

Figure 2. Share of affirmative answers in a 2014 Eurobarometer Survey

Source: Special Eurobarometer 397

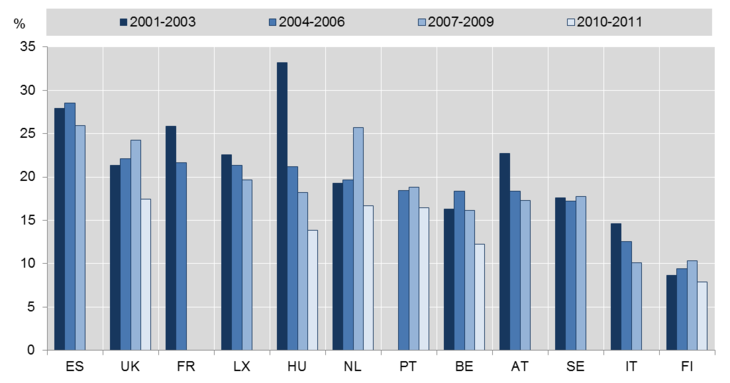

In terms of competition, 90% of Eurobarometer survey respondents agreed that corruption is part of the business culture in Italy: the highest value in the EU28 (see Figure 2 above[2]). Similarly, and perhaps more worryingly, 75% believe the only way to succeed in business is to have political connections: the second highest value in the EU28, after Cyprus. This is perhaps unsurprisingly paired with one of the lowest (and declining, even pre-crisis) shares of start-ups among OECD EU economies, as displayed in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Fraction of start-ups (less than 3 year old) among all firms

Source: C. Criscuolo, P. N. Gal and C. Menon (2014), “The Dynamics of Employment Growth: New Evidence from 18 Countries”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers no. 14

Gross fixed capital formation is close to a 20-year low[3]. The stock of FDI inflows was around 20% of GDP in 2013, the smallest figure in the OECD EU after Greece (11%)[4].

Regarding the quality and composition of Italy’s government expenditure, I will only report one striking number: for large public works alone, the Italian Court of Auditors estimates corruption (including indirect losses) to amount to as much as 40% of total public procurement value.

It must be acknowledged that a niche (largely model-based) literature suggests that corruption might be beneficial to growth in so far as it allows to bypass overburdening government regulation (e.g. Leff, 1964). However, this is not of great relevance to the Italian case as these studies were focused on developing and least developed countries, where institutional quality is extremely poor. Furthermore, the empirical literature is quite unanimous in acknowledging a strong and negative relationship between long-term growth and corruption (for a review of the empirical literature, see Campos and Dimova, 2010).

Over the past few years, a wave of corruption scandals has pushed successive Italian governments to take policy action. In November 2012, Mario Monti passed a large anticorruption law, aiming at preventing and prosecuting corruption in the public administration. Renzi’s government has largely been pushing for a toughening of those provisions. However, past success cases suggest that more forceful action will be needed if corruption is to be significantly curtailed.

Seeking to reduce corruption mainly by punishing corruptors and corrupted, without changing the institutional arrangements that made it possible for corruption to emerge, is unlikely to prove successful (OECD, 2013b). Past cases like Singapore[5] and Hong Kong show how the key words of an effective and radical anticorruption campaign should be: i) simplification, ii) transparency, and iii) clear accountability[6].

Extrapolating these principles to an Italian context could mean, for example, adopting a wide-ranging Freedom of Information Act, regulating lobbyism[7], restructuring public examinations with the aim of improving bureaucratic quality, furthering the use of job rotations within the public sector, abridging government formalities and paperwork[8], privatising public utility companies or, at least, reducing their monopoly power. To codify and ingrain these key principles in all levels of government activity, “persistent political will and vigilance, including at the highest level of government” will be needed (OECD, 2013a).

Tackling corruption in Italy is not only a matter of fairness, at a time when citizens are being asked to tighten their belt, but is likely to have major repercussions on the country’s private and public investment, FDI, competition, innovation, and ultimately, long-term growth. All of which, Italy is in dire need of.

[1] Throughout this contribution, corruption is defined in the broadest of senses as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain”, in line with Transparency International.

[2] Spain is also depicted, as a country that is currently undergoing a wave of corruption scandals.

[3] See “Boost for Italian economy as investment climate starts to warm” – Financial Times, 8 April 2015.

[4] See “Recent trends in FDI activity in Europe” – Deutsche Bank, 21 August 2014.

[5] “The origins of the country’s persistently superior performance in corruption control can be traced to the radical reforms designed and implemented by the People’s Action Party (PAP) during the period 1959/60, which transformed the country from one plagued by corruption to one of the ‘cleanest’ in the world” (OECD, 2013a).

[6] Bianco (2012) shows how factors particularly associated with corruption are, inter alia, excessive bureaucratic burdens and low quality of the bureaucracy.

[7] Without a specific lobbying regulation, nor an established registrar of lobbyists, Italy ranks as one of the worst countries in Europe in terms of transparency of lobbying, and is hence at high risk of suffering from an undue influence of the private sector on public decision-making (see Transparency International, 2015).

[8] For example, the World Bank’s 2015 Doing Business survey shows how dealing with construction permits (for a warehouse) takes on average 233 days (against 150 days in the OECD), putting Italy on the 116th place in the world.