Confronting the risks: corporate debt in the wake of the pandemic

As European economies emerge from lockdowns, it is becoming clearer that corporate debt has reached critical levels.

Publicly guaranteed credit and moratoria have been the main instruments used by governments to support companies during the pandemic. By the end of 2020, €318 billion in loans was subject to moratoria according to the European Banking Authority, with the bulk of suspensions then expiring in the first quarter of this year. There has also been substantial use of public credit guarantees, with Italy and Spain among the most active users of this instrument. Additional credit of 8% and 9% of GDP respectively was created in these two countries by end-2020, in part backed up by the European Investment Bank’s €25 billion European Guarantee Fund.

These measures were highly effective in the acute phase of the crisis but addressed only short-term liquidity shortfalls. The loans had relatively short grace periods, so will soon add to debt-service requirements. Moreover, even though governments would assume the risks of default, the banks that extended guaranteed credit would rank level with other senior lenders in any insolvency proceedings.

The upshot is that additional debt offered throughout the pandemic has left the EU corporate sector more vulnerable to insolvencies, and less likely to muster additional hiring and investment. In the recovery, excessively indebted companies are likely to delay investment and focus on deleveraging. At current levels of leverage, many businesses no longer have any margin for error. The slow investment recovery in the aftermath of the 2008 European crisis could be repeated: according to one empirical study roughly 60% of the drop in euro-area business investment in that period was due to excessive leverage in some firms.

‘Hybrid’ debt

What debt-distressed enterprises therefore need are long-term financial liabilities that are relatively junior in the creditor hierarchy.

To address the scale of the recapitalisation requirement, which was last estimated by the European Commission at somewhere between €720 billion and €1.2 trillion, institutional investors must be involved. Equity injections on this scale are unlikely to come from private investment funds, let alone from the still limited IPOs on European equity markets. In any case, small and medium-sized companies (SMEs) generally have very limited access to capital markets, and are reluctant to take on board new owners. Banks, with their established branch networks and knowledge of SMEs’ credit risks and growth prospects, should be relied on to identify suitable borrowers and target loans only to viable companies with sound growth prospects.

Subordinated debt and other instruments where the lender’s risks are similar to those for equity could be an alternative to common equity. This is typically long-term debt, often with a grace period, which leaves the lender in a very junior position in case borrowers default. At that point, the lender would be highly exposed to a write-down or conversion into equity, in line with the local insolvency regime which determines risk premia.

Various forms of such debt are offered across Europe, including Italian mini-bonds, payment-in-kind bonds or convertible bonds. The common characteristic is that the lender shares a much larger portion of risk and, in most cases, such instruments will not dilute ownership once they convert. Overall, the European market is relatively small. Between 2016 and 2019, non-financial firms in the EU (excluding the UK) issued about €68 billion in subordinated debt, compared to about €569 billion in ordinary bonds. There was remarkable growth in 2020, though once SMEs are highly indebted they are more likely to be cut off from such high-risk debt.

A number of barriers and market failures may justify some government support for this form of credit. From the perspective of investors, the true deterioration in credit may not be well understood, given the past year of moratoria and fiscal support schemes. A further problem is that each lender will price the cost of credit to reflect the probability of default and recovery rates in each individual borrower. A high risk premium will therefore restrain demand for such loans, and will not reflect the economy-wide benefits arising from reduced borrower leverage. Finally, there is wide variation in the treatment of subordinated debt instruments under national tax, accounting and regulatory rules, which affect capital costs for investors and banks.

Governments assume risks akin to equity investors

Given these challenges, many governments are now expanding support through their national development banks. At least ten EU development banks offer equity participation, either through direct investment or as co-investment in equity funds. An OECD survey suggested these products have so far been focused on start-up companies, rather than established companies with good growth prospects. But governments should avoid a direct ownership role, and the moral hazard this gives rise to.

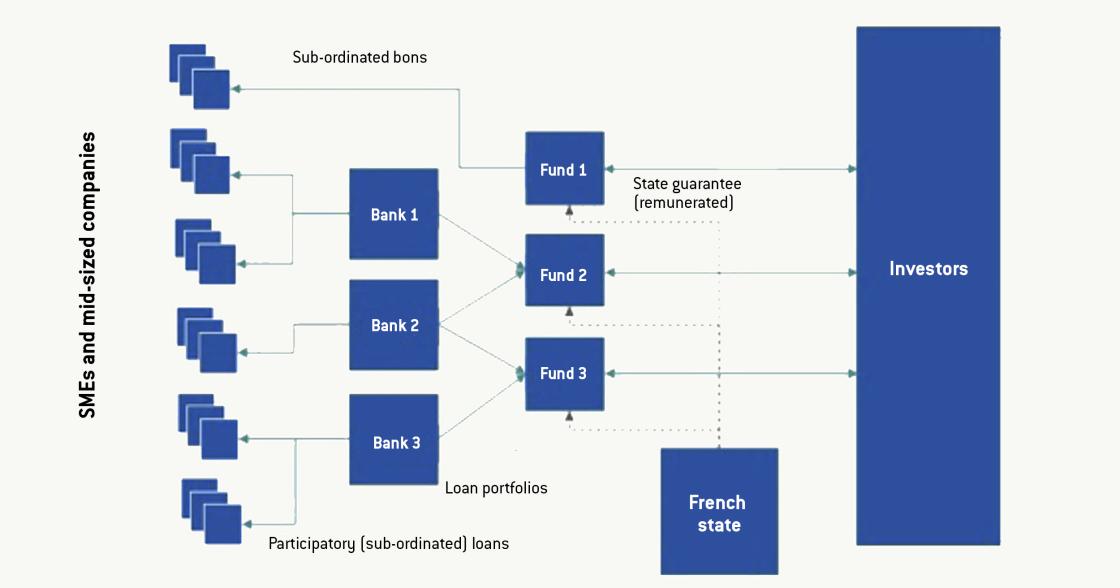

Some countries are targeting their support more carefully. The European Commission in March approved a French scheme that Spain is also considering in a similar form. French banks will offer subordinated loans (known as prêts participatifs or participatory loans) to SMEs and will then sell portfolios of such loans to investment funds (Figure 1). These funds would in parallel issue subordinated and long maturity bonds to larger companies. These investment funds would in turn market these portfolios to institutional investors, such as insurance companies, with the French state guaranteeing the first 30% of portfolio losses.

The long grace periods and repayment periods are in excess of what would be offered in the market and will considerably ease the debt service burden facing SMEs in the near future. As these loans and bonds would be deeply subordinated, companies can effectively treat them as equity.

From the banks’ perspective such loans will be attractive because they will stabilise their clients’ solvency. As only about 10% of loans need to be retained by banks as ‘skin in the game’, the high bank regulatory capital charges that would normally be imposed on highly risky instruments are minimised (150% for subordinated loans). End investors will likely find long-term and high-yield instruments with a partial sovereign guarantee an attractive investment. For insurance firms, state-guaranteed portfolios of SME loans are more attractive than exposures to individual firms, for which capital charges under the Solvency II Directive rise sharply as loan maturities lengthen and credit quality declines.

No doubt there are some pitfalls. While only SMEs and mid-sized firms with a minimum credit rating are included, end investors may be concerned that banks will cherry-pick the better exposures for themselves. Given the cap on the interest rate, riskier SMEs may not have access to such loans. Residual uncertainty over the demand by end investors under the scheme may discourage the structuring of such portfolios of high-risk subordinated debt. The guarantee extended by the state to investment funds is remunerated on market terms, though the loans represent a much greater contingent liability to the state than was the case with the previous loan guarantee (rating agency S&P Global, for instance, estimates a recovery rate of only 27% on subordinated loans, compared to 73% for the most senior claims on defaulted borrowers).

Figure 1: Illustration of the French guarantee scheme

Source: European Commission.

Potential in the EU Capital Markets Union

The European Commission approved the French scheme under the exceptional provisions of the EU State Aid Temporary Framework. As companies emerge from moratoria and the recovery gains hold, approval of new loans will need to extend well beyond the expiry of the framework at the end of 2021. While investment funds can of course be marketed across the EU or even beyond, French investors will likely be the main investor base for the French scheme. Eligibility for the sub-loans is largely limited to French SMEs, and French investors will be most comfortable in taking a risk in a French insolvency proceeding. Given the significant credit risks inherent in the instrument, this is not a scheme that can be replicated easily in fiscally weak EU states, or where large institutional investors are scarce.

One benefit may be that the scheme catalyses capital market instruments that have been quite limited to date within the EU market. To allow subordinated and high-risk loans to develop in the long term, EU countries should quickly bring into line the treatment of such instruments in tax and regulatory rules. Insolvency rules, which are crucial for investors, have converged somewhat but of course remain a deeply national affair. The ongoing EU reform of capital requirements in the insurance sector under the Solvency II Directive could be important to attract a broader group of long-term investors into such corporate and high-risk debt.

Recommended citation:

Lehmann, A. (2021) ‘Confronting the risks: corporate debt in the wake of the pandemic’, Bruegel Blog, 28 April