China pushing 'build now, pay later' model to emerging world

China will be the largest contributor to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which aims to become the first global institution headquartered in

During the last couple of years, China has pushed a number of grandiose proposals that could make it the world's largest lender for development projects.

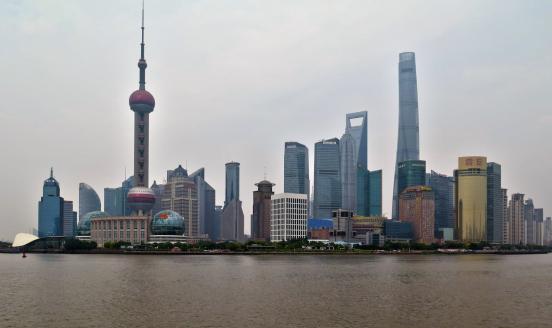

the AIIB aims to become the first global institution headquartered in China

The most recent is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which aims to become the first global institution headquartered in China. China will be the largest contributor to an AIIB that will be capitalized at no less than $100 billion. Two other initiatives are a $40 billion fund to revive economic relations along the old Silk Road and the BRICS Development Bank, which has another $100 billion in capital and is also headquartered in China.

In all, we are looking at a potential pool of capital comparable to that of the World Bank.

While much of the attention has centered on China's motives, as well as how the initiatives would challenge the status quo, more interesting questions are whether emerging economies will benefit and what kind of construction-led development model is to come with them.

Plenty of countries seem happy to sign up as recipients.

For example, China just unveiled $45 billion in lending to Pakistan, announced during President Xi Jinping's stop-over in Islamabad ahead of the Bandung Conference on Asia-Africa relations. The package, which constitutes China's largest single overseas investment deal, will go toward the development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor -- which aims to grant China direct access to the Indian Ocean and will involve the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects in the region. Details have not been fully disclosed, but the money is expected to be split between energy and transportation projects.

President Xi has also just agreed to lend billions of dollars to Russia and Belarus for infrastructure projects.

Openness to Chinese lending is understandable, given that developing economies have large infrastructure investment needs. The Asia Development Bank has estimated that Asia will need $8.3 trillion beyond existing financing capabilities between 2010 and 2020.

In this context, Chinese loans may be an important lifeline for countries that have not managed to secure access to financing from the ADB or World Bank.

China's terms of lending are believed to be broadly in line with market interest rates, and the government does care about getting a decent return on its loans. Under guidelines set down by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, concessional lending means a five-year grace period on payments and near-zero interest rates. Chinese loans do not fall into this category.

China does offer more flexibility than other lenders

But China does offer more flexibility than other lenders. In some cases, it accepts commodities rather than cash as repayment. This may be more attractive to emerging economies. Geopolitical considerations may also lead China to accept more lenient conditions if circumstances warrant it.

But while Chinese terms may be more lenient, borrowers should also be aware of potential pitfalls.

There is often a lack of transparency surrounding the financial conditions of Chinese loans, which means recipient countries could find it difficult to judge whether they've been given a good deal.

Second, and more importantly, there are no guidelines setting quality standards of infrastructure projects financed by the AIIB or the other two initiatives.

We can look at the experiences of countries that have borrowed from China in the past to see how things may evolve.

Sri Lanka is perhaps the most paradigmatic example in Asia, as is Venezuela in Latin America and Angola in Africa. Over $5 billion in infrastructure projects were funded by China -- often built by Chinese corporations -- between 2009 and 2014. There is now plenty of basic infrastructure in place that has benefited Sri Lanka. But projects were often unsolicited, few were open to competitive bidding and some turned out to be wasteful vanity landmarks.

Bribes were paid. As a result, the new government in Sri Lanka is reassessing deals signed between former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and China.

It would be unfair to extrapolate Sri Lanka's case to the rest of emerging Asia, but it seems clear that the new development banks will need to establish adequate processes to justify projects and to make sure infrastructure is properly built.

It goes without saying that the world in which only Bretton Woods institutions governed emerging economy development was not perfect: There has been too much red-tape and loads of conditions that sometimes might have been used to keep projects in the hands of these institutions' major shareholders.

All in all, and notwithstanding the previous caveats, if China-led development banks manage to bring more competition to the world of development assistance, they may not be a bad thing at all.

Emerging countries will have more financing options

Emerging countries will have more financing options, but they should watch out for hidden costs and learn from China's own pragmatism: Put economics at the forefront when choosing whether to accept loans, rather than just sitting there and waiting to be handed a check.

This blog post was originally published in Nikkei Asian Review.