Chart of the week: Political groups in the European Parliament since 1979

The results of the European Parliament election of May 22-25 have been described as “a shock, an earthquake”. The long-term trends, however, indicate

True, the shifts in Britain and France have been among the most dramatic. But the vote in other countries suggests a more nuanced view

Much of the pan-European comment, as always, comes from the London-based international press focusing on the outcomes in the UK and, to a lesser extent, in the familiar old neighbor across the Channel. True, the shifts in Britain and France have been among the most dramatic. The UK Independence Party (UKIP) came in first, as did the National Front in France, while the governing French Socialist Party did worse than ever. But the vote in other countries suggests a more nuanced view.

In Italy, the governing centre-left and pro-European Union (EU) Democratic Party won decisively. In Spain, the dominance of the two mainstream parties was eroded, but the gainers were mostly pro-EU even when they were anti-system. Conversely in other countries, key parties were pro-system from a domestic perspective, some of them even governing in their countries, but nevertheless anti-EU – for example, Hungary’s Fidesz and indeed the UK’s own Conservatives. About everywhere, and as usual in European elections, national political developments overwhelmingly influenced voters’ choices.

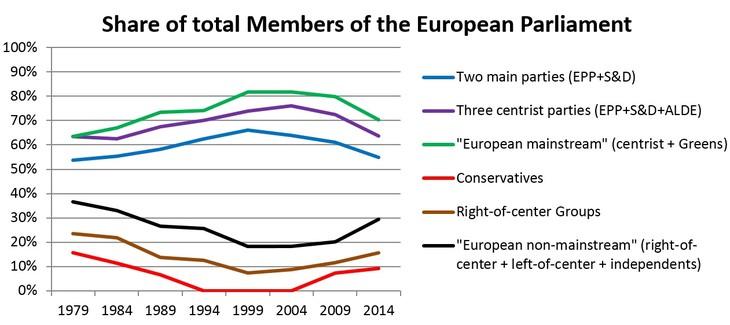

A longer-term perspective is reflected in in the chart above, showing all European Parliament elections (one every five years) since the first one by universal suffrage in 1979. Political groups in the Parliament have occasionally changed name and composition in terms of national member parties, but there is enough continuity to observe trends.

The two main groups have always been the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the centre-left Socialists & Democrats (S&D). The centrist liberals, now known as Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe (ALDE), have also been present since inception, as has a group of communist and other left-of-centre parties, now called European United Left / Nordic Green Left (EUL/NGL). The Greens appeared in the 1984 election in alliance with regionalists, and have had their own group continuously since 1989. The UK Tories joined the EPP in the 1994, 1999 and 2004 but have been the core of a Conservative group both before (European Democrats) and after (European Conservatives and Reformists).

Various other right-of-centre nationalist groups have come and gone, most recently the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) party, which includes UKIP and Italy’s Five-Star Movement. There was also a separate regionalist group following the 1989 election, and a split centrist group following the one in 1994. Finally, each parliament has a number of independents, currently at record level since France’s National Front failed to join or constitute a group.

The chart shows the shares of total Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) for different political groupings on the basis of this typology. Given the EU system’s significant deviation from the principle of electoral equality, this breakdown may be somewhat different from the EU-wide popular vote. Also, the absolute number of MEPs has almost doubled because of successive EU enlargements, from 410 in 1979 to 751 today.

One obvious fact springs from the graph: Europe has been there before

One obvious fact springs from the graph: Europe has been there before. Until the 1990s, the overall balance of political forces in the European Parliament was remarkably similar to the current one, even though its national components have changed somewhat. Compared with the heyday of the “European mainstream” in the 1999, 2004 and 2009 elections, the earlier period saw stronger parties both on the left and on the right of the centrist block of EPP, ALDE, S&D and Greens (who may be radical on certain policies but are here included in the “European mainstream” in terms of their stance on EU integration). Strikingly, the legislatures that followed the 1984 and 1989 elections were the ones when Jacques Delors was President of the Commission, an era often seen in Brussels as the halcyon days of European integration.

A key question for the future, of course, is whether the recent trend will continue, and whether the “anti” parties may increase their gains further in the next election, scheduled in 2019. While an extrapolation of the chart may suggest such a prospect, it is far from inevitable. An optimistic reading of the appointment of EPP lead candidate Jean-Claude Juncker, the former prime minister of Luxembourg, as Commission President (which remains to be confirmed by a vote of the European Parliament itself) suggests that the next election may differ markedly from previous ones, including this year’s.

Given the Juncker precedent, EU member states’ citizens may be motivated to elect a specific party with a positive outcome in mind (their preferred pick for the top job) as opposed to a protest vote. If confirmed, this could trigger another trend reversal.