Challenges to debt sustainability in advanced economies

The gross general government debt-to-GDP ratios in many advanced economies have reached the highest levels in peacetime history and continue to grow,

Rapid expansion of sovereign debt

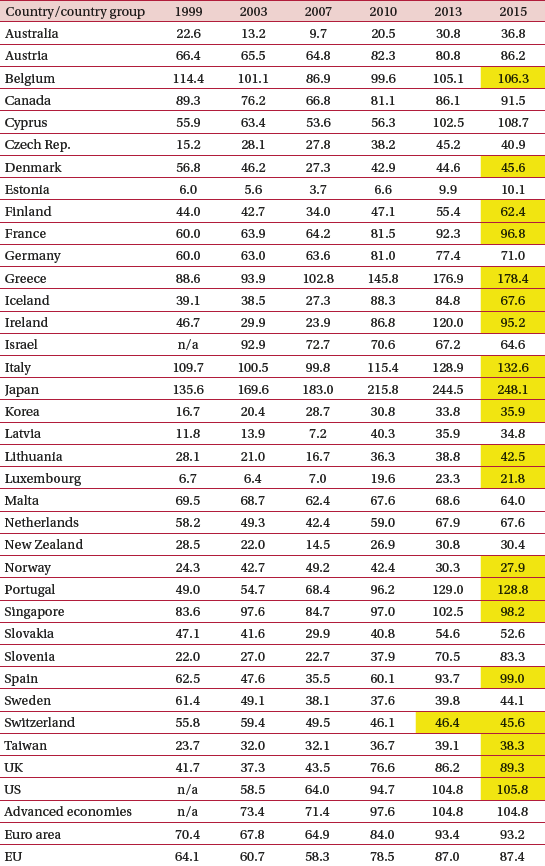

The gross general government debt-to-GDP ratios in many advanced economies have reached the highest levels in peacetime history and continue to grow (Table 1), calling into question sovereign solvency in these countries. This worrying picture can be seen as the consequence of the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and policy response to this turmoil, including large-scale bailouts of financial institutions and active use of countercyclical fiscal measures. However, in a few of the largest economies (the US, Germany, France, the UK) expansion of public debt had already started in the early 2000s or even earlier (Japan). In 2015, only Belgium, Denmark, Israel, Malta, Sweden and Switzerland recorded a lower debt-to-GDP-ratios as compared to 1999.

Source: IMF WEO, April 2016. Note: cells in yellow indicate IMF staff estimates.

In the same year, general government gross debt approached 250 percent of GDP in Japan, and exceeded 100 percent of GDP in Greece, Italy, Portugal, Cyprus, Belgium and the US, in some cases by large margins. In Spain, Singapore, France, Ireland and Canada it was between 90 and 100 percent of GDP, and in the UK, Austria and Slovenia it was between 80 and 90 percent. Only three countries where debt exceeded 80 percent of GDP as result of the 2007-2009 crisis (Germany, Iceland and Ireland) managed to start decreasing their debt-to-GDP ratios recently.

Furthermore, the macroeconomic situation in 2015 was relatively favourable in most advanced economies – economic growth was close to potential and there were historically record-low nominal and real interest rates. Such conditions will not necessarily continue in the medium to long term. In case of new adverse shocks, whether economic or political, global or country-specific, which result in the deterioration of growth prospects or higher real interest rates, or both, the situation could easily get out control.

Debt sustainability and financial stability risks

Our debt sustainability simulations (Dabrowski, 2016) for those advanced economies whose gross public debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 80 percent in 2015[1], suggest that the current record-low interest rates and post-crisis growth recovery should be used for fiscal consolidation now.

First, we determined the primary fiscal balance-to-GDP ratios required to stabilise countries’ 2015 debt-to-GDP ratios assuming that, in subsequent years, the rate of real GDP growth and real interest rates will remain at the 2015 level. Under such optimistic assumptions most countries do not need to conduct additional fiscal adjustment to stabilise their gross debt-to-GDP ratios at the 2015 level. France and the US must undertake relatively modest fiscal tightening (less than 1 percent of GDP) while Cyprus, the UK, and Canada should do more on this front.

In the second step, we tested the scenario under which real interest rates might return to a historical average of +2 percent, for example, as a result of exit from extra-loose monetary policies. Growth rates would remain on the 2015 level, the same as in the first simulation. In the second simulation, all countries except Ireland, Cyprus and Slovenia, would have to undertake fiscal adjustment to prevent further expansion of their debt-to-GDP ratios. Japan should tighten by almost 9 percent of GDP, which may be difficult politically, even if it has room to increase taxes (especially VAT) and its net public debt (net of international reserves, public pension assets, net credits to other countries, etc) amounted to “only” 126.2 percent of GDP in 2015.

Stabilisation of high debt-to-GDP ratios on the 2015 level seems to be insufficient to avoid future fiscal risks. One cannot rule out sudden changes in market sentiment as a result of either external or country-specific shocks (economic or political) resulting in a rapid increase of interest rates and denying a given government market access.

For this reason, we also examined a scenario under which highly indebted countries decrease their gross debt-to-GDP ratios by 2 percentage points annually from its 2015 levels (for EU countries this debt reduction is required by the Stability and Growth Pact when it exceeds 60 percent of GDP). However, achieving such a goal would require an improvement in the primary fiscal balance by an additional 2 percentage points of GDP, as compared to the results of the first two simulations. For most countries, this may be an affordable task under the 2015 interest rates but much more difficult when real interest rates increase to 2 percent or even higher level.

Apart from the risk of sovereign default, excessive public debt might also have a negative impact on financial stability. Bruegel’s database developed by Merler and Pisani-Ferry (2012) with later updates shows that commercial banks in some euro-area countries (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain, Germany, and Ireland) have high exposures to marketable sovereign debt.

In Japan, in 2015 net credit to the nonfinancial public sector accounted for approximately half of the net domestic assets of depository corporations, or 114.3 percent GDP, and this ratio has remained pretty stable over recent years (IMF, 2016, Table 2). At the same time, the Bank of Japan’s net credit to the non-financial public sector quadrupled between 2011 and 2015 (reaching 57.8 percent of GDP in 2015), which suggests an increasing pace of de-facto public debt monetisation by the Japanese monetary authority.

In addition to increasing commercial banks’ sovereign exposures, sovereign debt instruments have other important functions that are based on the assumption of their risk-free character. There is, for example, their role as collateral in central bank lending to commercial banks, central bank international reserve assets, reserve assets of sovereign wealth funds, life insurance companies, pension funds and other investment funds, and as liquidity instruments in daily financial market operations. Greece’s sovereign debt crisis demonstrated its far-reaching disruptive consequences not only for the domestic and euro-area financial sectors, but also for the European Central Bank’s monetary policy operations. It is hard to predict the scale of potential negative effects in case of public debt sustainability problems in larger countries such as Japan, Italy, France or the UK.

Unfunded pension, healthcare and long-term care liabilities

The gross public debt statistics does not include all government liabilities, for example, those related to public pensions, healthcare and long-term care systems. Although unfunded pension, healthcare and long-term care liabilities do not need to be rolled over on the market they must be paid down in future budget periods, including the costs of their servicing (when they are subject to indexation). Therefore, they add to future expenditure streams.

According to 2015 Aging Report of the European Commission (2015), several EU member states are on the way to decreasing their public pension expenditure by 2020 as result of pension reforms undertaken in the last decade. In Latvia, Hungary, Denmark, and Bulgaria pension expenditure decrease would be more than 1 percent of GDP, in Sweden, Poland, Greece, Slovenia, Croatia, and Cyprus – between 0.5 and 1 percent of GDP. However, in other countries the expected pension spending cuts are either smaller, or expenditure will stabilise at a relatively high level, or will continue rising (Malta, Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Belgium, and Luxembourg). In some cases (Lithuania, Slovenia, Cyprus and the UK) the positive effects of past reforms will expire after 2020. Thus, among the highly-indebted countries, Belgium, Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, the UK, Italy, France and Austria should undertake further pension reforms, as should less-indebted Germany, Finland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Malta and Lithuania.

The picture looks more worrying in respect to future changes in public healthcare and long-term care expenditure (European Commission, 2015). All EU countries will record increases in this kind of public spending by 2030. For the entire EU, the magnitude of this increase, only for demographic reasons, will be twice the pension expenditure increase. The biggest increases (by 1 percent of GDP or more) will be faced by Malta, Finland, Croatia, Denmark, Netherlands, Slovenia, Portugal, Ireland, Austria, Germany, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and France. Except for demographic reasons, healthcare expenditure will also increase due to technical progress.

Negative impact on economic growth

Several empirical analyses (eg Checherita and Rother, 2010; Reinhart and Rogoff, 2010; Kumar and Woo, 2010; Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli, 2011) point to the potential negative impact of public debt on economic growth once the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds a certain threshold, for example, 80 or 90 percent. It works through various channels such as absorbing part of private saving (which could be used for investment otherwise), leaving less room for public investment spending (because of high debt service costs), uncertainty related to potential higher future or risk of sovereign default and associated financial crisis. Such uncertainty may harm consumer and investment spending leading to more Ricardian rather than Keynesian effects of fiscal expansion when public debt is high.

This is one more argument to use the current opportunity of very low interest rates to start decreasing gradually the record-high public debts rather than further expand public borrowing.

References

Cecchetti, S.G., M.S. Mohanty and F. Zampolli (2011) ‘The Real Effects of Debt’, BIS Working Papers, No. 352, September, available at http://www.bis.org/publ/work352.pdf

Checherita, C. and P. Rother (2010) ‘The Impact of High and Growing Government Debt on Economic Growth. An Empirical Investigation for the Euro Area’, Working Paper Series, No. 1237, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1237.pdf

Dabrowski (2016): Are advanced economies at risk of falling into debt traps?, Bruegel Policy Contribution, Issue 21, November 10, https://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/PC_20_16-25-11-16.pdf

European Commission (2015) ‘The 2015 Aging Report. Economic and Budgetary Projections for 28 EU Member States (2013-2060)’, European Economy, No. 3, available at http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2015/pdf/ee3_en.pdf

IMF (2016) ‘Japan: 2016 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report’, IMF Country Report, No. 16/267, available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2016/cr16267.pdf

Kumar, M.S. and J. Woo (2010) ‘Public Debt and Growth’, IMF Working Paper, WP/10/174, available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10174.pdf

Merler, S. (2014) ‘Home-(Sweet Home)-Bias and other stories’, Bruegel Blog, 8 January, available at https://bruegel.org/2014/01/home-sweet-home-bias-and-other-stories/

Merler, S. and J. Pisani-Ferry (2012) ‘Who’s afraid of sovereign bonds?’ Policy Contribution, No. 2012/02, Bruegel, available at https://bruegel.org/2012/02/whos-afraid-of-sovereign-bonds/

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff (2010) ‘Debt and Growth Revisited’, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, available at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/24376/1/MPRA_paper_24376.pdf

[1] Except Greece, which does not have access to private markets and is subject of continuous rescue program.