Can Greece become competitive overnight?

In a controversial piece recently published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), Anders Aslund illustrates how the problem wi

In a controversial piece recently published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), Anders Aslund illustrates how the problem with Greece’s adjustment programme was not excessive austerity but rather a slow pace of fiscal consolidation, matched by too few reforms. In his own words, “Latvia did far more than Greece in structural reforms, because the correlation between fast fiscal adjustment and structural reform is strong. On the latest World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index [pdf], Latvia ranks 23, while Greece ranks 61, as the country with the very worst business environment in the European Union together with Cyprus and Croatia.”

Aside from the fact that Malta is also a member of the European Union and ranks 94th on the above mentioned index, what I contend is that when measuring reform effort what should be looked at is not the current position of a country on a competitiveness ranking, but rather by how much it has improved during the programme’s admittedly limited time-frame.

When reading structural reform effort through these lenses, one sees that Greece has made significant progress, climbing almost 50 positions over 5 years, from its 109th place in 2008-09[1]. Given that Latvia is apparently the benchmark, it must be noted that the country was already ranking very well in 2008-09 (30th worldwide) and improved moderately since then. In its 2014 Report, the World Bank itself using slightly more sophisticated metrics identifies Greece as one of the top broad reformers worldwide (8th to be precise).

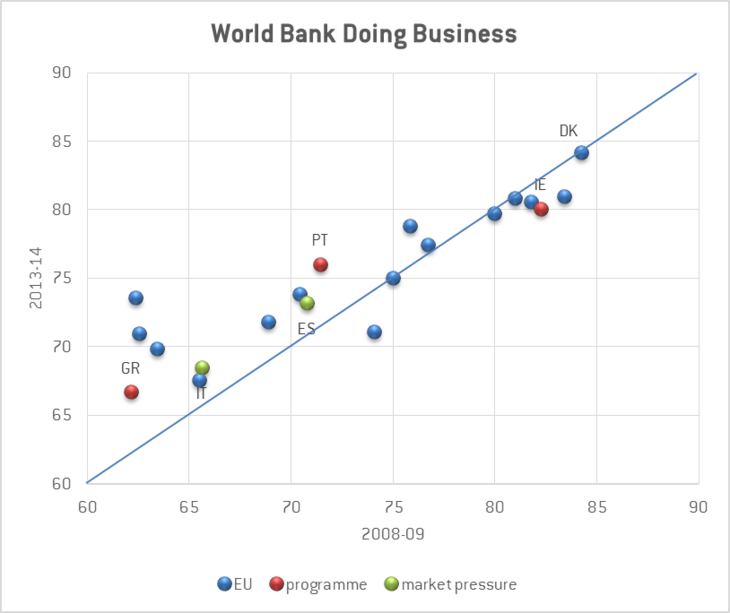

As rankings are affected also by the relative performance of others, the chart below looks at the World Bank doing business score (on a scale from 1-100) for selected EU countries. As noted by Mr. Aslund, Greece is indeed at the lower end of the spectrum, whereas Denmark outperforms its European partners (4th worldwide and 1st in the EU in the 2015 Doing Business report).

As can be seen, Greece has improved its ease of doing business in line with Portugal, and more than Italy or Spain over the same period. This is particularly noteworthy as, at the same time, Greece was the country experiencing the most severe economic downturn and reforms usually involve some sort of initial fiscal cost of implementation.[2]

Source: World Bank Doing Business

Hitherto, I have looked at the World Bank Doing Business data in a principle of continuity with the PIIE article. However, these findings are not limited to this index. A cross check with internationally recognised indicators of competitiveness confirms the finding that Greece has been undertaking significant reforms. As a further example, in its commentary to the latest release of its Product Market Regulation index, the OECD notes: “Even though there was little progress on average in the OECD, several countries implemented important reforms over the past five years [...]. The country with the largest improvement overall is Greece, followed by Poland, Portugal and the Slovak Republic”.

In terms of labour market reforms, as measured by the Employment Protection Legislation (EPL) index of the OECD, Greece has indeed progressed less than Portugal (but more than Spain). However, this might be due to the fact that Greece needed to carry out less reforms under this heading, as it now stands broadly in line with the OECD’s EPL average, whereas Portugal remains well above.

Clearly, the latest competitiveness rankings do matter in so far as they illustrate how further and significant progress is yet to be made. However, it would be naïve to believe that a country with admittedly limited administrative capacity, high corruption levels, political instability, and severe spending constraints could achieve top scores like Denmark or Latvia overnight. Possibly it’s also thanks to these reforms that Greece has returned to growth in 2014 – and this is something also the new Greek government should acknowledge, before hastily unravelling the efforts of the past.

[1] Note that the timing of the World Bank reports is such that DB2010 incorporates reforms taken over the period 2008-09, and similarly DB2015 (released in October 2014) covers the period 2013-14.

[2] As recognised by the OECD in Chapter 1 of its Going for Growth Report (2009), certain reforms require permanent restructuring of public budgets, such as frontloading cuts in revenue or spending increases.