Can China bail out Putin?

Even with help from China, Russia will be unable to mitigate the immediate impact of Western sanctions.

The unprecedented sanctions imposed on Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine are likely to have devastating consequences. But this will depend on whether Russia manages to bypass the sanctions or, at very least, mitigate them.

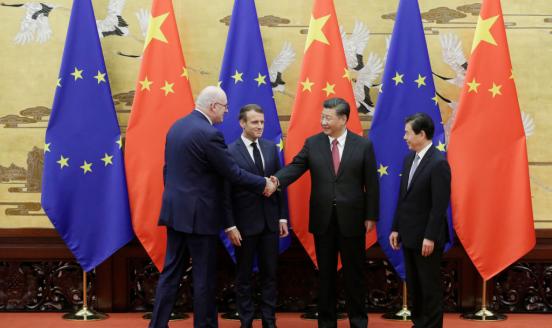

China offers a clear path to do this, because of China’s economic size and financial clout and also thanks to its growing importance for Russia, since Putin announced Russia’s pivot to the East during his 2012 election campaign. Importantly, China’s political position on Russia’s attack against Ukraine remains unclear, if not contradictory. Chinese policymakers have been highly critical of Western sanctions on Russia, blaming the West for the situation in Ukraine. Only a month before the invasion, on 4 February during the Beijing Olympics, presidents Xi and Putin signed a cooperation framework, the importance of which was reaffirmed by China’s foreign minister on 7 March. But to what extent can Russia really mitigate the impact of Western sanctions via its economic and financial linkages with China?

Russia may face even more sanctions, including a potential European Union ban on energy imports from Russia. This would clearly be the most damaging measure for Russia as the EU’s energy imports from Russia are four times bigger than China’s (Figures 1-4). Notwithstanding the hampering of potential action by excessive EU dependence on Russian energy, key western economic sanctions are twofold:

First, the German government has stopped the certification process of Nord Stream 2 and the United States has imposed sanctions on the pipeline operator. Second, exports of semiconductors to Russia have been banned, extending to other major exporters including South Korea and Taiwan. Semiconductors are essential inputs for Russia’s high-tech industry, including for military equipment, which is a key source of export revenues for Russia after oil and gas. In addition to their economic value during a military conflict, exports of military equipment have contributed to building Russia’s successful strategic relationships with countries such as India, which explains India’s decision to abstain on the draft resolution on Ukraine at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on 25 February. The impact of the inability of Russia to import semiconductors should not be underestimated.

Russia is also now limited in its ability to transact in dollars, euros, sterling and Japanese yen, and a number of Russian banks have been cut off from SWIFT. While Iran offers a precedent for these sanctions, it is not directly comparable given the broader interlinkages of Russian financial institutions with the rest of the world. Possibly the most unprecedented measure is the freeze of the Bank of Russia’s hard currency assets, as well as those of the Russian sovereign fund and the Ministry of Finance.

How much can Russia rely on China to mitigate the impact on the Russian economy?

From a political point of view, China’s response is a combination of official neutrality with strong criticism of the West for being ultimately responsible for the conflict because of its attempts to expand NATO and because of previous sanctions on Russia. On the economic and financial fronts, China has so far been pragmatic. Chinese state-owned banks have been instructed to comply with Western sanctions and several have already discontinued letters of credit with Russian counterparts. But China has announced a lifting of limits on wheat imports from Russia, which were in place for some time due to phytosanitary concerns. This was one of the measures announced in the 4 February China-Russia cooperation agreement. China is thus complying with the letter but not the spirit of the law. China is ready to help Russia, without risking a legal spat with the West by breaching sanctions.

Stronger trade ties with China and Western sanctions will likely push Russia to accept, reluctantly, the renminbi as a means of payments. According to SWIFT data, Russia’s use of the renminbi has increased rapidly in the last few months and renminbi deposits in Hong Kong have spiked in the last couple of months. Russia can count on stepping up trade with China to mitigate the impact of Western sanctions on its economy but only if it is ready to accept an increasing relevance of the renminbi in the Russia economy.

The speed of economic and financial dependence on China will depend on Russia’s own needs. As long as the EU continues to import gas from Russia at elevated prices, Russia can count on a large enough pool of hard currency for imports (with an estimated current account surplus of $200 billion to $250 billion) of which 80% needs to be surrendered to the central bank. So, for the time being, Russia should be able to avoid economic collapse as long as hard currency revenues are enough for imports and servicing of foreign currency debt. This would mean Russia does not need to jump into China’s arms for help. But, were the EU to ban oil imports, and the US to strike a deal with oil producers to pump more oil and/or free up strategic reserves, the shock to the Russian economy would be much bigger and would greatly increase the value of any help from China.

For China, the value of increasing economic cooperation with Russia is apparent, as clearly shown by the 4 February agreement. The cooperation framework includes two projects to build gas pipelines in Russia for export to China. The Power of Siberia II pipeline would link Russia’s Yamal peninsula gas province, which feeds pipelines directed towards Europe. But it will be years before Russia can count on China to absorb the bulk of its gas production.

The ban on exports of semiconductors to Russia cannot be cushioned by China for two main reasons. First and foremost, China’s semiconductor companies, including its largest and most successful, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, do not have access to many of the parts needed to build sophisticated semiconductors, especially since the US included it on its so-called ‘entity list’ in 2020, resulting in the ban of US technology exports (including semiconductors) to SMIC. Second, China’s semiconductors are not sophisticated enough to serve all the needs of Russia’s high-tech companies. This is clearly a bottleneck for Russia.

Payment systems

To mitigate financial sanctions, China’s international payment system (CIPS) might be of use. At first sight, it is tempting to think that it offers Russian banks a platform to conduct transactions away from the scrutiny of the West. In reality, CIPS cannot be of immediate help to bypass sanctions for a number of reasons.

First, CIPS uses SWIFT as a messaging system with no immediate substitute, at least not for cross-border transactions. Second, even if a new messaging system became operational, it would need to be adopted by a large number of financial institutions. SWIFT has 11,000 members in 200 countries and conducts 42 million transactions per day, while CIPS has about 1,000 members in half the number countries. Third, CIPS does not have either the liquidity or the members to make it comparable to the platform that virtually all banks currently use for their international transactions, the Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS). The volume of payments processed through CIPS has grown rapidly since September 2020, but it counts only 13,000 transactions per day, compared to over 240,000 for CHIPS.

Beyond the immediate future, there is no doubt that China can leverage its economic size to foster the use of CIPS, making it liquid and relevant enough for Russia to operate away from CHIPS. Still, Russia would need to accept the renminbi for commercial transactions with China, including its exports. At this stage, it seems unlikely Russia would want to enter a renminbi-centric financial system and reduce its access to other reserve currencies, which are convertible.

Russia could use the People’s Bank of China’s digital currency, the E-CNY, for cross-border payments with China. The use of the E-CNY for Russian international payments would bypass CHIPS and does not need SWIFT as messaging system. However, the Bank of Russia has not yet signed a memorandum of understanding with PBoC for cross-border use.

Lack of hard currency access

Russia also needs to find respite from the West’s freezing of its hard currency reserves. Nearly half of Russia’s $643 billion in foreign reserves are held in euros and dollars (as of 30 June 2021), and nearly three quarters are investments located in countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia. Meanwhile, about a fifth of Russian reserves are in gold physically located in Russia. Any trading in this component of its reserves is also likely to be impacted by the sanctions.

Still, Russia holds the equivalent of $90 billion in renminbi deposits at the PBoC, which should be ready to use for imports from China. However, the non-convertibility of the renminbi also implies that the Bank of Russia cannot convert its renminbi reserves into hard currency unless the PBoC does so. The Bank of Russia also holds the equivalent of $24 billion in IMF special drawing rights. It is hard to think of any other central bank other than the PBoC that can help the Bank of Russia convert its drawing rights into liquid currency. The PBoC will likely be reluctant to do this as it could be interpreted as a breach of sanctions. The Bank of Russia may thus need to focus on renminbi-denominated reserves for future rainy days.

Beyond the reserves, the Bank of Russia also counts on a swap line with the PBoC, giving it access to an additional 150 billion renminbi. But this also cannot be converted in hard currency. In the event that Russia can no longer export to the West and needs to step up imports, both its renminbi reserves and the swap line should cushion the collapse of imports but the cost will be obvious: rapidly increasing economic and financial dependence on China. There is no such thing as free ride out of Western sanctions for Russia.

Conclusion

Russia does not really need China’s help just yet. However, if the West were to increase the pressure by blocking energy exports, the Russian economy would suffer even with Chinese help. China’s lacks the ability to offer immediate support. Russia lacks the physical connectivity to redirect gas exports from west to east. China’s financial infrastructure is not developed enough: CIPs still depends on SWIFT and is not yet liquid enough. The Chinese digital currency does not yet offer cross-border transactions of any relevance, and Russia has not yet signed up to it. It is hard to imagine that the Bank of Russia will be keen to foster the circulation of a non-convertible currency at a time when the ruble is tanking. In fact, the process of renminbi-isation of the Russian economy would make monetary management in Russia even harder.

China could aid Russia by converting Russia’s renminbi reserves into hard currency. But the reputational risk of breaching western sanctions would be huge. Over time, China will be able to support the Russian economy as new pipelines are built to redirect gas from Europe to China and CIPS becomes a credible alternative to CHIPS. But this is clearly more appealing for China than for Russia. China would be able to strengthen its energy security by becoming Russia’s largest – if not only – importer of oil and gas. Second, progress in renminbi internationalisation would accelerate without having to give up capital controls. Beyond its political commitment in the 4 February declaration, China has an economic incentive to support Russia as long as it does not fall afoul of Western sanctions. For Russia however, strong dependence on the Chinese economy and its financial system is to be avoided. This would really be a very distant second best, in terms of Russia’s desired outcomes from its war against Ukraine.

Recommended citation:

García-Herrero, A. (2022) 'Can China bail out Putin?', Bruegel Blog, 9 March