Blogs review: Profits without investment in the recovery

What’s at stake: Paul Krugman has kicked off an interesting debate in the blogosphere about a new disconnect between profits and production, which may

What's at stake: Paul Krugman has kicked off an interesting debate in the blogosphere about a new disconnect between profits and production, which may have slowed the recovery. In contrast to previous downturns, investment has been especially slow to recover. This seems paradoxical given that profits have recovered from the slump. Krugman provides an explanation for this puzzle based on the growing importance of monopoly rents in the 21st century economy.

Paul Krugman writes that the growing importance of monopoly rents is producing a new disconnect between profits and production. Since around 2000, the big story has been one of a sharp shift in the distribution of income away from wages in general, and toward profits. But here’s the puzzle: Since profits are high while borrowing costs are low, why aren’t we seeing a boom in business investment?

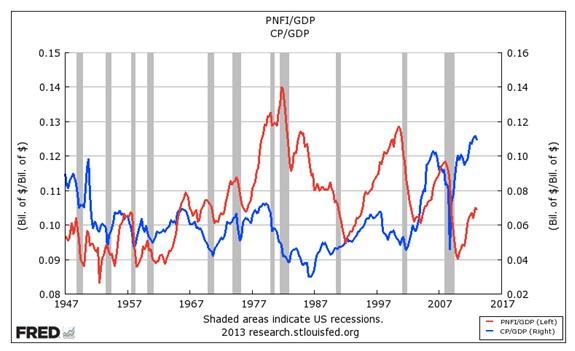

Private Nonresidential Fixed Investment (PFNI, red) and Corporate Profits After Tax (CP, blue)

Note to Brad DeLong: you’re getting that PNFI is back to its pre-crisis level because you express it in terms of potential GDP.

Buttonwood writes that US business investment has not recovered from the slump even though profits have. The Cleveland Fed notes that in the United States, private fixed investment has averaged about 15.3 percent of GDP over the postwar period; however, more recently it has run below this ratio. It crashed down to 10.5 percent in 2009 and has since hovered around 13 percent. This is unusual since investment is more volatile than income. Typically, investment will fall more than GDP during recessions, and it did in the last recession; but historically it then rebounds just as sharply. This gives the ratio of investment-to-GDP a “V-shape” over recessions. So far the most recent case has not displayed this same pattern. In contrast to previous downturns, investment has been especially slow to recover after this most recent recession.

Paul Krugman writes that you might suspect that this can’t be good for the broader economy, and you’d be right. If household income and hence household spending is held down because labor gets an ever-smaller share of national income, while corporations, despite soaring profits, have little incentive to invest, you have a recipe for persistently depressed demand. I don’t think this is the only reason our recovery has been so weak — weak recoveries are normal after financial crises — but it’s probably a contributory factor.

Explaining the gap between profits and investment

Paul Krugman writes that there’s no puzzle here if rising profits reflect rents, not returns on investment. A monopolist can, after all, be highly profitable yet see no good reason to expand its productive capacity. And Apple provides a case in point: It is hugely profitable, yet it’s sitting on a giant pile of cash, which it evidently sees no need to reinvest in its business.

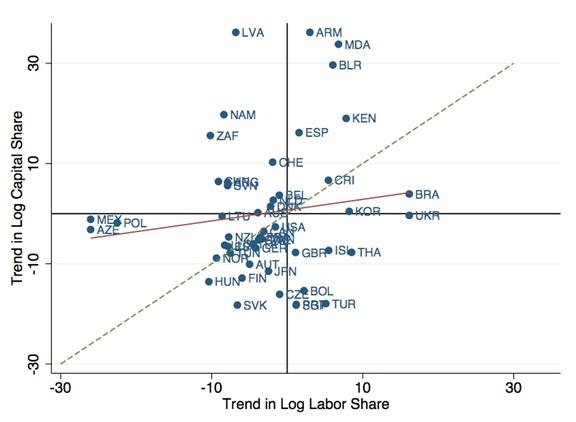

Owen Zidar sends us to a paper by Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman that provides evidence consistent with the idea that markups may have increased in a non-trivial way. It’s a bit hard to see but many large countries, including the US, appear to be fairly close to the 45 degree line with both lower labor and capital shares, which is roughly consistent with the growing importance of markups. However, as shown by the best-fit line, labor has lost more than capital on average.

Buttonwood writes that there are alternative explanations than that of increasing rents: one might be that US companies are investing abroad, not at home; another might be that business are worried about the growth or regulatory outlook; a third might be that there not many capital-intensive projects that look attractive.

Sketching a model for explaining the decrease in both capital and labor shares

Paul Krugman considers an economy in which two factors of production, labor and capital, are combined via a Cobb-Douglas production function to produce a general input that, in turn, can be used to produce a large variety of differentiated products. Now consider two possible market structures. In one, there is perfect competition. In the other, each differentiated product is produced by a single monopolist. So, with perfect competition, labor receives a share a of income, capital a share 1-a, end of story. If products are monopolized, however, each monopolist will charge a price that is a markup on marginal cost that depends on the elasticity of demand. A bit of crunching, and you’ll find that the labor share falls to a(1-1/e). But who gains the income diverted from labor? Not capital — not really. Instead, it’s monopoly rents. In fact, the rental rate on capital — the amount someone who is trying to lease the use of capital to one of those monopolists receives — actually falls, by the same proportion as the real wage rate.

Paul Krugman explains that in national income accounts, of course, we don’t get to see pure capital rentals; we see profits, which combine capital rents and monopoly rents. So what we would see is rising profits and falling wages. However, the rental rate on capital, and presumably the rate of return on investment, would actually fall. What you have to imagine, then, is that some factor or combination of factors has moved us from something like version I to version II, raising the profit share while actually reducing returns to both capital and labor.

Brad DeLong writes that such a setup holds the possibility of explaining not just a rise in inequality, an extraordinary growth in the share of firms that have no visible support in production, falling unionization, and falling median wages, but also high average Q with low marginal Q, and hence depressed investment.

Nick Rowe tweaks Paul Krugman’s model. In the Krugman’s model, consumption and investment goods are perfect substitutes in production, with a marginal rate of transformation always equal to one, so that (under competition) the price of the capital good will always equal one (taking the consumption good as numeraire). This means that the rate of interest will always be equal to MPK. A decrease in 'a' will reduce labor's share, MPL and wages for labor, increase capital's share, MPK and rentals on capital, and raise the rate of interest. An increase in 'A' will raise both wages and capital rentals, and raise the rate of interest. In the second model, consumption and investment goods are still perfect substitutes in production, but the marginal rate of transformation now equals 1/A, so that (under competition) the price of the capital good will always equal 1/A. As A increases over time, capital goods become cheaper in terms of consumption goods. The rate of interest must equal the rate of return on owning capital goods, but that rate of return is lowered by the fact that the price of those capital goods is falling over time. Here is an explanation of a higher capital share but lower real rate of interest: (1-a) has increased; but Adot/A has increased too.