Blogs review: Battle of narratives over the European recovery

What's at stake: Many European leaders have started to claim credit for the recent improvement in economic conditions in the Eurozone. The boldes

What’s at stake: Many European leaders have started to claim credit for the recent improvement in economic conditions in the Eurozone. The boldest example was certainly the op-ed written last week by Wolfgang Schauble where Germany's Federal Minister of Finance used the good news to claim vindication over the skeptics of the European approach to the EMU crisis. Beyond the colorful reactions that it generated (see for example Ambrose Evans-Pritchard), this controversy certainly shows that the battle for the narrative of the recovery has already started.

The positive signals from the Eurozone

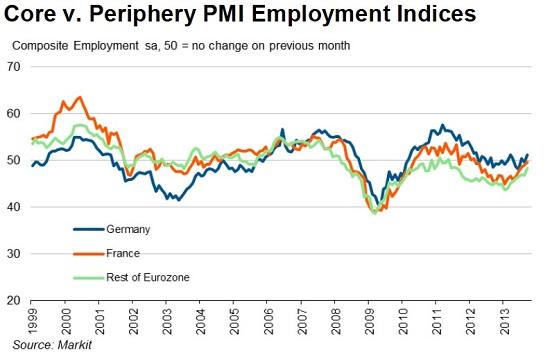

Marco Buti and Pier Carlo Padoan write that over the past few months, economic news from the Eurozone has been encouraging. After six quarters of contraction, GDP surprised on the upside in the second quarter, expanding by 0.3% compared to the previous quarter. The latest GDP release also shows further progress in intra-Eurozone rebalancing; with a strong export performance in some vulnerable member states and welcome signs of strengthening domestic demand in the core. Overall, the recession has now given way to a modest recovery, and key indicators are signaling a continuation along this path in the second half of this year and a recovery gaining traction next year. Joe Weisenthal writes that the good news is that even the periphery appears to be recovering.

Source: Business Insider

Parallel universe: Schauble vs. the blogosphere

Wolfgang Schauble writes that what is happening turns out to be pretty much what the proponents of Europe’s cool-headed crisis management predicted. The fiscal and structural repair work is paying off, laying the foundations for sustainable growth. In just three years, public deficits in Europe have halved, unit labor costs and competitiveness are rapidly adjusting, bank balance sheets are on the mend and current account deficits are disappearing. In the second quarter the recession in the eurozone came to an end.

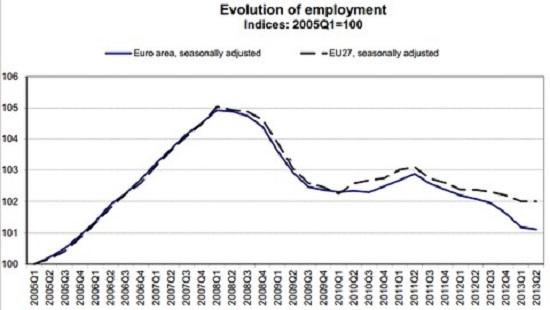

Paul Krugman writes that it takes quite a lot of chutzpah to claim that this is a record of successful preparation for structural transformation. Wolfgang Schäuble’s piece in the FT, in which he claims complete vindication because Europe has had one, count it, one quarter of growth is pretty awesome even relative to expectations. Bear in mind that the record on jobs looks like the picture below.

Andrew Watt writes that the question is whether this counts as success. If in an economy we shut down one in five factories and offices – more or less the experience in Greece and some other crisis countries – we get an apparently strong recovery even if we put just one in ten of those workplaces back to work: growth of 2% would be recorded – but this conceals the fact that we have only recouped one tenth of the 20% loss of output previously suffered. The real issue is that the euro area, after entering and exiting the global financial crisis in line with the US, Japan and others, has massively underperformed compared with global benchmarks.

Francesco Saraceno write that although technically speaking Schauble did not lie when writing that “domestic demand is the main driver of growth in Germany today”, this has only been true for the past two quarters. But maybe it could have occurred to him that this is because of recession in the Eurozone? And the current account doesn’t show that Germany is rebalancing.

The role of structural reforms in the European recovery

Wolfgang Schauble writes that in the “boom” phase, several members of EMU let labor grow expensive and their share of world trade shrink. As the bust came, jobs vanished and public finances deteriorated. The success of the eurozone adjustment was not only the produce of a European consensus, it followed a well-established recipe, not just by Germany but by the UK in the 1980s, Sweden and Finland in the early 1990s, Asia in the late 1990s and many other industrial and emerging countries.

Francesco Saraceno write that Schauble cites the UK in the 1980s, Sweden in the early 1990s, East Asia in the late 1990s, and of course Germany in 2003-2005 to support the view of “successful austerity and reform”. First, as Krugman noted, most of these countries could depreciate their currencies. Second, during all of these episodes restructuring happened against a background of strong global growth. It is clear that today’s period is peculiar in that austerity for peripheral European countries is happening in a globally weak context.

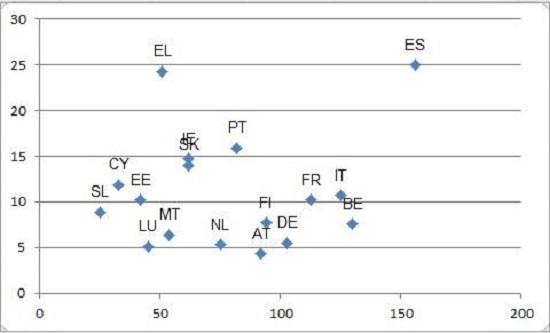

Andrew Watt writes that Schäuble’s assertions that while Germany was busy reforming the countries worst hit by the crisis were expanding their welfare states, or burdening their economies with additional taxes and regulations does not hold empirically. The European Commission’s database of labor market reforms, LABREF shows that there is no correlation between the extent of “structural reforms” over the 2000-2008 period and employment success today.

Source: Andrew Watt

Antonio Fatas writes that while talking about uncertainty and reform always sounds right, the evidence is either weak or inexistent. Spain or Italy or France or even Greece improved their (product markets) regulation much more than the USA or Canada but their (potential) growth performance was significantly weaker.

Uncertainty and the slow European recovery

Marco Buti and Pier Carlo Padoan write that a notable difference with the US is the drawn-out contraction of investment in the Eurozone after the Great Recession. In the US, investment fell sharply in 2008-09, but has registered positive growth in ten out of 14 quarters since the beginning of 2010. In the Eurozone, investment picked up briefly in 2010, but declined for eight straight quarters thereafter. They argue that three conditions are necessary for investment to pick up: 1. Reducing policy uncertainty. 2. Repairing the financial system. 3. Creating new investment opportunities.

Antonio Fatas writes that the evidence is in favor of the hypothesis that fiscal policy can explain most of the relative underperformance of some economies in the post 2008 period. The evidence is certainly much stronger than any of the factors that Buti and Padoan present. But somehow fiscal policy did not make it to their list of top three factors.