Beyond the training gap: learning foundational skills on the job

Low-skilled workers tend to have jobs that are less likely to foster foundational skills. This worsens skills gaps and income inequality.

As employers struggle increasingly to find workers who fit the jobs on offer, it has become crucial to equip the European workforce with skills for the jobs of the future. Most lists of such skills drawn up by employers include not only technical (or hard) skills but also foundational (or soft) skills. These can be grouped into three categories: cognitive, interpersonal and self-management. Cognitive skills include critical thinking, problem-solving and analysis. Interpersonal skills include the ability to work in teams and to collaborate, along with communication and emotional intelligence. Self-management skills include self-regulation, resilience and adaptability.

Beyond these three fundamental categories, both McKinsey and the World Economic Forum include technology or digital skills as a fourth foundational skillset of the future. The extent of demand for these foundational skills is apparent when analysing online job ads (Figure 1). Of the 15 most-requested skills, 12 are from the three foundational categories, while two others fit into the digital category.

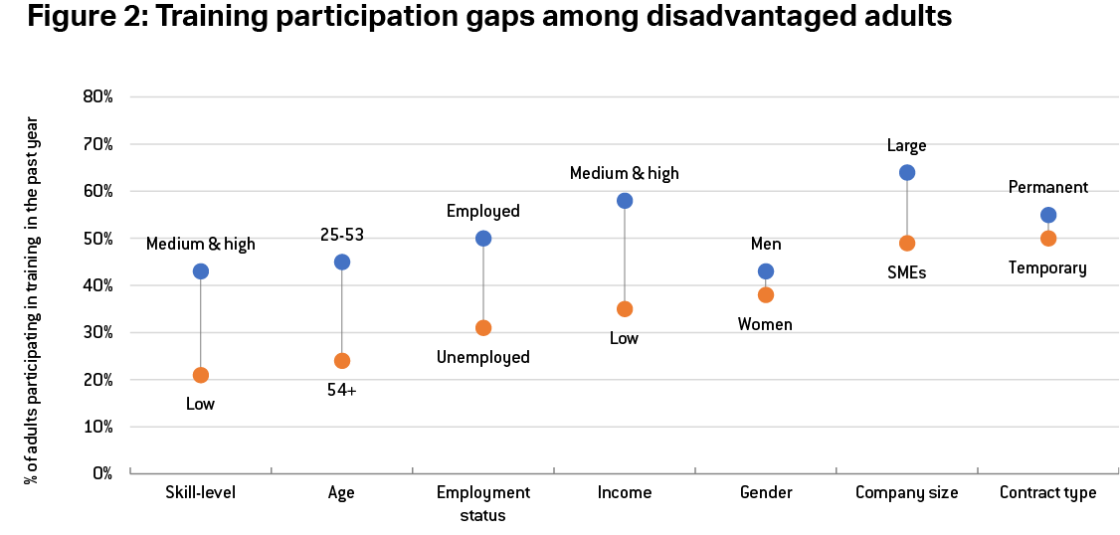

The demand for digital skills implies that education curriculums will need to be adapted, while targeted reskilling through vocational education and training should be offered to workers. In practice though, participation in adult training is lowest among those who need it most: the unemployed, the low-skilled, the over-54s and low-wage earners systematically take up less training than their employed, high-skilled, prime-age and high-income counterparts. Figure 2 shows the uptake (in %) for each of these groups. This training participation gap is well-documented throughout Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, and recommendations to policymakers focus on increasing the coverage, inclusiveness and effectiveness of formal training.

Source: OECD, Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems.

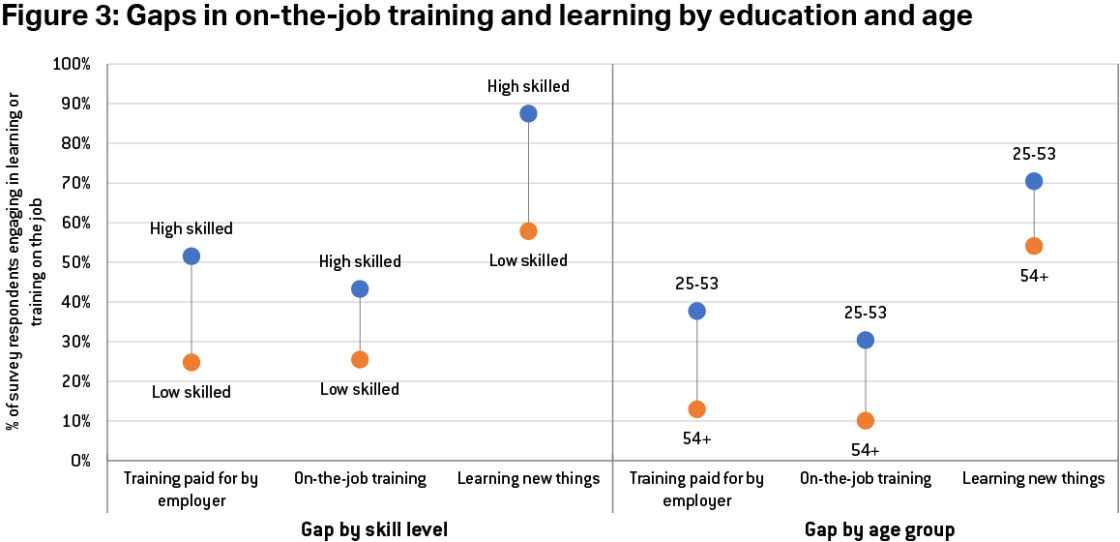

However, workers can learn new skills in many ways beyond formal training courses. Policymakers should note that when it comes to cognitive, interpersonal and self-management skills, “adults learn best by doing”. The most effective adult learning is autonomous, self-directed, practical and goal-oriented. In the context of the workplace, this type of informal learning is known as ‘on-the-job learning’ (as opposed to more formal types of structured learning, called training; for definitions, see CEDEFOP). Vulnerable groups already suffering from the formal-training gap mentioned above are equally disadvantaged when it comes to opportunities for informal on-the-job learning and personal development. While the general level of informal learning is greater than formal training, low-skilled and older workers indicate that they have fewer opportunities to learn new things at work than high-skilled and prime-aged workers (Figure 3).

Source: Bruegel based on Eurofound, 6th European Working Conditions Survey. Note: Based on the number of survey respondents who answered ‘yes’ to questions y15_Q53f – “Generally, does your main paid job involve learning new things?”, Y15_Q65ab_lt – “Over the past 12 months, have you undergone training paid for or provided by your employer?” and y15_Q65c – “Over the past 12 months, have you undergone on-the-job training (co-workers, supervisors)?”

These gaps in on-the-job learning and training arise because disadvantaged workers are more often in jobs that offer fewer opportunities for learning and development. While over 85% of managers, professionals and technicians say they get to ‘learn new things’ at work, this proportion drops below 50% for machine operators and elementary occupations (such as cleaners). The trend is similar for the two formal training indicators (training provided by employers and on-the-job training). All occupational groups engage less in formal training than in informal learning, but the training indicators drop below 30% for service and sales workers, craft workers, machine operators and elementary occupations (Figure 4).

Differences between occupations in the informal learning opportunities arise from differences in job and organisational design. ‘Job design’ refers to the tasks involved in the job and the autonomy or influence workers have in carrying out those tasks. Workers in higher-level occupations carry out more complex tasks and have more leeway to choose which methods work best for their work. These job characteristics are essential for building cognitive and self-management foundational skills. Especially when it comes to being able to influence decisions that are important for one’s own work, this indicator drops very steeply from the upper occupational categories downwards (Figure 5).

These inequalities in opportunities for personal development through on-the-job learning should be of great concern for policymakers who want to ensure an inclusive future of work. Occupations that offer less opportunity to develop foundational (cognitive, interpersonal and self-management) skills through on-the-job learning are exactly those most likely to be exposed to robot automation, and which are less teleworkable during health crises. Furthermore, these occupations typically pay the least (Figure 6). The occupational gap in on-the-job learning thus threatens to exacerbate inequalities, given current future-of-work trends.

As the best preparation for your next job is your current job, it is worrying that jobs at risk of automation offer little opportunity for personal development and the acquisition of foundational ‘skills of the future’. Most European Union policy responses to this problem have focussed on prompting workers to take learning into their own hands (see for example the European Commission’s December 2021 proposal on individual learning accounts and micro-credentials). Some EU countries (like Belgium) also require employers to invest a certain percentage of their yearly wage bills in training for their workforces, or to provide a minimum number of training days to each employee.

However, more could be done in terms of job design. Mirroring the call for a ‘skills passport’ that provides a record of workers’ skills beyond formal degrees, employers should also be incentivised to be transparent about a job’s learning content or its job design. Such employer transparency could be achieved through voluntary self-assessment tools, mandatory public disclosures and public rankings or ratings on job quality. Each of these approaches comes with challenges related to scaling and cost, customisation and actionability, and political feasibility. Another line of thought would include job-quality and job-design measures in non-financial (environmental, social, governance) standards for investors.

A simpler approach, however, would be information about job design in job vacancy descriptions. Job ads already show remarkable trends in how employers compete for workers in tight labour markets. For example, employers have become more transparent and accommodating about remote work in their job ads since the COVID-19 pandemic. Employers are also reducing formal education requirements and promoting employer training offerings to fill open positions.

Similarly, employers could be transparent in job ads about how much control workers will have over cognitive tasks including planning, choosing methods and quality control. Job ads could also explain whether workers will be required to solve issues individually or collaborate in teams, with superiors, or other departments and how this problem-solving is organisationally supported. This would give workers an insight into how much they can expect to improve their cognitive, interpersonal, and self-management skills when applying for a job.

If job ads were more transparent about job design and the learning content of jobs, firms would compete for workers on job aspects beyond wages and contractual conditions. Workers would be keener to work for firms advertising jobs with high learning content, thus raising the average skill-intensity of jobs. Policymakers could support employers similarly to how they already support job seekers: just as Europass offers CV templates and digital credentials for job seekers, the EU could offer job ad templates with specific job design and learning-content sections for employers.