Argentina, plus ça change…

Recent primary elections in Argentina saw the defeat by a wide margin of President Macri. This fueled market volatility given expectations of a revers

When Macri assumed office in 2015, markets viewed his economic programme favourably (the Argentine Merval stock index rose by 25 percent when the results were announced). Many economists also expressed optimism, yet cautiously highlighted the extent of Argentina’s underlying weaknesses. The final term of the administration of Fernández de Kirchner had seen monetary financing of a growing fiscal deficit and increasing inflation (with high levels of consumption and low investment). The IMF saw Argentina on the verge of a balance of payments crisis. Extensive bureaucratic obstacles to the convertibility of pesos (termed cepo cambiario) had resulted in the loss of any appeal for foreign investors. State intervention caused important microeconomic distortions, hidden by doctored national statistics.

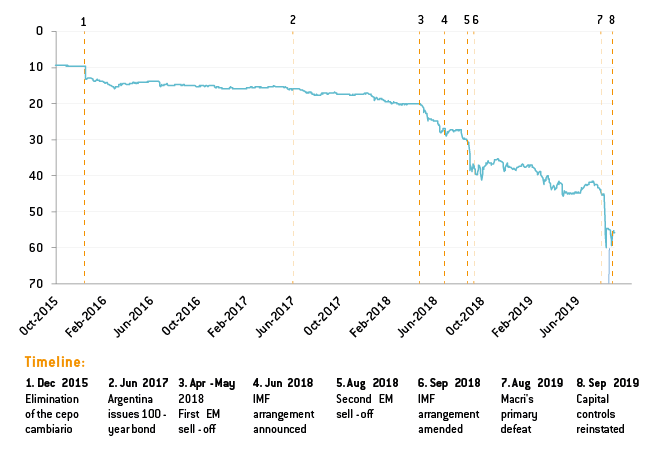

Figure 1: Pesos to US$

Source: Bloomberg

Faced with this environment, Macri opted for a gradual approach to economic reform (gradualismo). He eliminated the cepo cambiario and negotiated a deal with creditors that reestablished access to international capital markets. Capital inflows kept the exchange rate just below 20 pesos per dollar throughout 2016 and 2017; investor optimism even allowed Argentina to issue an oversubscribed 100-year bond.

Macri’s administration also announced plans for the central bank (BCRA) including a reduction of monetary financing and the introduction of an inflation targeting regime. Deficit reduction was pursued through a reduction in spending and tax reform. Medium-term targets included single-digit inflation and a primary balance of zero by 2019; Argentina was on the way to normalisation. However, these policies were conditioned by gradualismo.

Figure 3: Primary fiscal deficit, debt & current account balance (actual and forecasts, % of GDP)

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook

By the final months of 2017, the IMF staff report warned of emerging tensions, focused on the risks of persistent inflation and primary deficit. BCRA credibility was weakened by their continued financing of the fiscal deficit (by about 1.5 percent of GDP in 2017) and inflation in 2017 was 24 percent. The IMF estimated the currency to be 10-25 percent overvalued.

Meanwhile, foreign currency borrowing had grown substantially, creating high external financing needs (by the beginning of 2018, 70 percent of the stock of government debt was dollar denominated). The Argentinian current account deficit was growing rapidly: it climbed from 2.7 percent in 2016 to 4.9 percent in 2017.

In April 2018, external financing needs caused growing market uncertainty, and investors began to sell short-term Argentinian debt. This was heightened by two additional developments. Firstly, drought resulted in a fall in agricultural exports (over 50 percent of Argentinian exports are agricultural/livestock) reducing dollar inflows. Secondly, dollar appreciation and falling risk appetite resulted in widespread capital flight from emerging markets. The ensuing balance of payment pressures were unsustainable and the peso began to depreciate heavily in early May, worsening dollar-denominated external financing requirements.

These circumstances gave Macri little choice; in May 2018 he requested IMF assistance to meet Argentina´s financing obligations. The fund approved a $50 billion stand-by arrangement in June, which was accompanied by a commitment to increase BCRA independence and stop central bank financing of fiscal deficits, as per a memo by the Ministry of Finance. Inflation and primary deficit targets were pushed back.

However, temporary stability from IMF assistance was short-lived. August saw large capital outflows from emerging markets, coupled with continued economic contraction in Argentina and an apparent failure to slow-down inflation. This caused another devaluation of the peso (the currency fell to almost 40 pesos per dollar after beginning the year at 20). Argentina’s economic performance was worse than that envisioned by the ‘adverse scenario’ in the IMF’s initial stand-by arrangement.

President Macri’s request for additional IMF assistance to meet financing obligations, announced on YouTube, heightened market fears and resulted in additional currency volatility. The situation stabilised when the fund increased the total value of the stand-by arrangement to $57.1 billion and agreed to significantly frontload assistance to 2018 and 2019.

After this revision, Argentina transitioned from an inflation targeting to a temporary monetary base targeting regime. New rules for central bank intervention in FX markets were also introduced to prevent arbitrary decisions. The Argentine government also committed to a 2019 primary fiscal balance, pushing a 2019 budget through Congress to achieve this target. Expectations were that it would result in a debt to GDP ratio peak in 2018 of 81 percent (it ultimately rose to 86 percent).

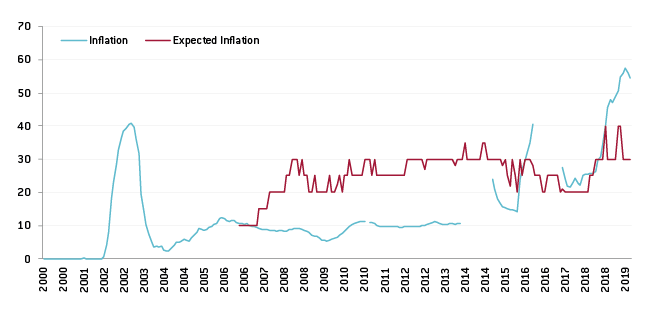

Moreover, 2018 inflation was 48 percent, largely driven by the deterioration of the currency throughout the year: the IMF estimated the 30 percent loss of peso value in August alone resulted in a month-on-month inflation of 6.5 percent in September and 5.4 percent in October. Inflation volatility is evident in the figure below, yet care should be taken with figures during the Kirchner years given evidence of government tampering (as affirmed by an official statement by IMF executive director for Argentina). Expected inflation is based on the median results of a 12 month inflation expectations survey by Torcuato Di Tella University.

Figure 4: Inflation

Source: Trading Economics I Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos & Torcuato Di Tella University

After the August 2018 episode, the revised IMF stand-by arrangement allowed for a gradual stabilisation, despite volatility in April 2019 driven by inflation. IMF inflation expectations for 2019 rose from 20 percent during the second review of the IMF stand-by arrangement (in December 2018) to 40 percent by the fourth review (in July 2019). Nonetheless, market volatility had largely subsided by May. During the three months before the primaries the economic situation appeared to be improving.

Argentina’s primary elections took place on the 12th of August. These are official national primary elections: all parties must take part and voting is mandatory. As parties had already chosen candidates, they worked as a mock election of sorts. Peronist candidate Alberto Fernández and his running-mate former President Fernández de Kirchner received 47 percent of the vote against Macri’s 32 percent.

These results stoked market fears of a partial return to the Kirchner years. As a result, the peso lost 23 percent of its value, while the Merval stock index fell by 48 percent (in dollars). This is the second largest single-day fall of any of the 94 stock markets followed by Bloomberg since 1950, beaten only by Sri Lanka in 1989 during the civil war. The performance of credit default swaps on Argentinian government debt indicated an implied 5-year likelihood of default of 70-75 percent.

Mr. Fernández, now the undisputed frontrunner, has done little to assuage market fears. His economic messaging remains ambiguous.

Despite initial market optimism when Macri came to power, the Argentinian economy has experienced economic contraction three out of the four years of his term. The Catholic University of Argentina estimates poverty rates have risen to 35 percent from 27 percent in 2017, while annualised inflation in Argentina reached 54.4 percent in July of 2019. Both primary deficit and inflation targets are en route to underperform this year, and both have been directly associated with recent instability.

Furthermore, the recent depreciation of the peso is expected to raise inflation further (as was the case after August 2018). Financial analysts predict debt to GDP will rise to between 95 percent (Fitch) and 100 percent (Capital Economics) by the end of the year. The former predict a fiscal deficit of 1 percent in 2019 and 2020. At the same time, capital controls have resulted in a stabilisation of the currency, and some economists have indeed defended their short-term value. However, their elimination was a flagship campaign promise; the Financial Times has described their reintroduction as a ‘humiliation’ for Macri.

Some economists, including many IMF directors, disagreed with Macri’s gradualist approach and advocated for more aggressive deficit reduction. Following recent underperformance, many have repeated this assessment. Claudio Loser, former head of the IMF western hemisphere division, believes the heart of the problem lies in an excess of borrowing fueled by overconfidence. Similarly, Kenneth Rogoff, former IMF chief economist, has been quick to criticise Macri’s paused approach to reform and deficit reduction, claiming Macri’s policies violated ‘the general principle (…) that when markets overshoot, policy has to overshoot.’ Brad Setser was also quick to point to the alarming pace of growth of dollar-denominated debt during the first two years of Macri’s presidency.

At the same time, other economists have recognised the difficulties Macri faced. Robert Kahn warned from the outset of the likely short-term contraction and public backlash of the necessary reforms. Similarly, Shannon O’Neill has underlined the systemic institutional issues that have hindered the Argentinian economy and the success of reform. These require more than four years to be dismantled. O’Neill also highlighted the role played by Argentina’s relationship with the IMF and the domestic political damage it has done to President Macri. The complicated dynamics of the relationship were also explored by Monica de Bolle and Gonzalo Huertas.