Designing a hybrid work organisation

Post-pandemic hybrid work models should be carefully planned, taking into account individual and organisational needs.

With the end of the pandemic in sight, organisations are rethinking when and where their employees will work. Over half of office workers want to keep working remotely for three or more weekdays and while employer enthusiasm is somewhat lower, this does seem feasible for 20%-25% of the workforces in advanced economies. Many companies will likely adopt a hybrid combination of on-site and remote work, with work from home estimated to be optimal at one to three days a week.

While this hybrid future creates opportunities for geographic mobility and for tackling regional inequalities, employers will need to find well-functioning models of organisational flexibility for their workforces. An update to the European Union’s 2002 Framework Agreement on Telework could facilitate the implementation of flexible working conditions in a way that ensures minimum protection for on-site and hybrid workers, while fostering harmonised standards within the EU single market.

Hybrid work comes with organisational challenges that are often grouped into three categories: bricks, bytes and behaviour, ie the spaces, tools and culture of remote work. What is missing is a fourth B, a blueprint for the allocation and coordination of tasks across time and space. While traditional organisational design deals with the question ‘who does what task?’ the hybrid model must additionally ask ‘who does what task when and where?’

Flexible work arrangements: when and where?

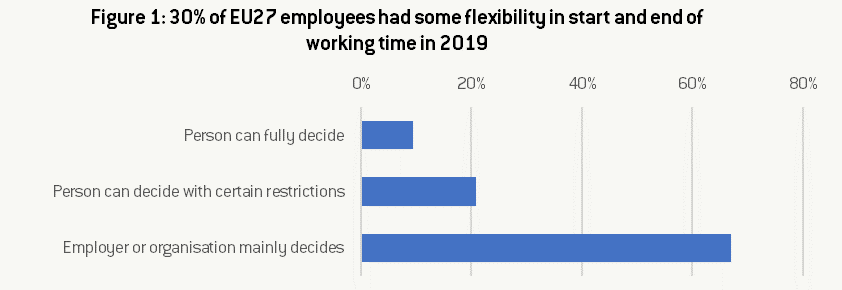

Flexible work arrangements have existed for over 50 years and cover both time and space dimensions. While in 2013 more than 65% of EU28 establishments offered some form of flexitime, only 30% of employees in the EU27 reported in 2019 having a say in the start and end times of their work day, and of those only a third could decide their hours without restrictions (Figure 1).

Source: Eurostat, LFSO_19FXWT02 (EU27, 2019).

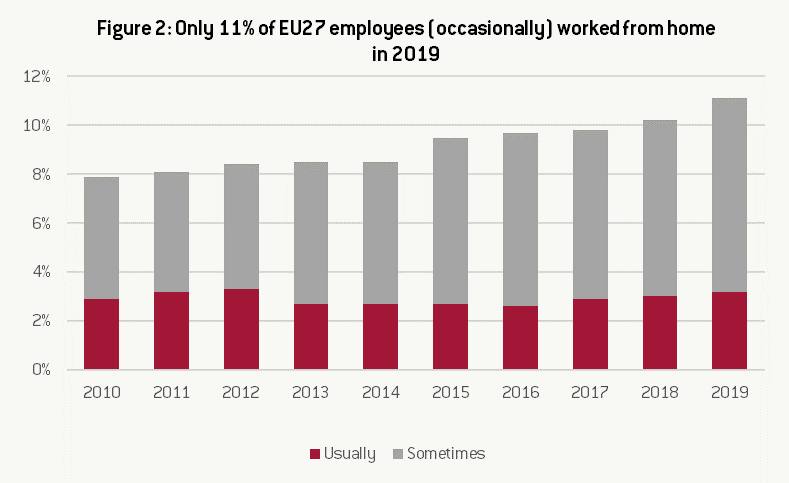

Flexibility in terms of the choice of working from home or another location was less prevalent than flexitime before the pandemic, at just above 11% in 2019, up from 8% in 2010 (Figure 2), with most telework taken up only occasionally.

Source: Eurostat, LFSA_EHOMP (EU27).

When rethinking flexible work arrangements, companies have to consider whether (1) to align employees’ working time (synchronous or asynchronous), and (2) whether to have employees work in the same space or be dispersed geographically. The traditional model of work is synchronous, co-located work, while flexitime and telework provide flexibility in terms only of when or where work is done. The combined freedom in terms of place and time of work is known as an anyplace, anytime policy (Table 1).

Challenge 1: Assessing the potential for individual flexibility

In reality not all jobs are equally suited for flexible working. In a hybrid model, employees do not fit neatly into one of the four squares of Table 1, but flexibility arrangements may vary. Designing a flexible work arrangement should start from the feasibility of hybrid work at the level of individual employees and work up to a more aggregate level, taking into account the externalities on co-workers. At the level of a single employee, organisations may want to consider at least three different aspects: roles, tasks and personal preferences.

Role-based flexibility can only go so far

Flexibility arrangements are often based on formal roles and their need for on-site or synchronous presence. Roles considered unsuited for flexible work arrangements typically require physical interaction with equipment (for example, machine operators, logistics workers and laboratory technicians) and with humans (for example, nurses and care workers). These physical interactions usually present a hard constraint on remote or asynchronous work. Social interactions (either cognitive or emotional) are a softer constraint that should at the least be synchronised in time and could benefit from physical co-location with colleagues or clients (such as managers, sales people, teachers and psychologists).

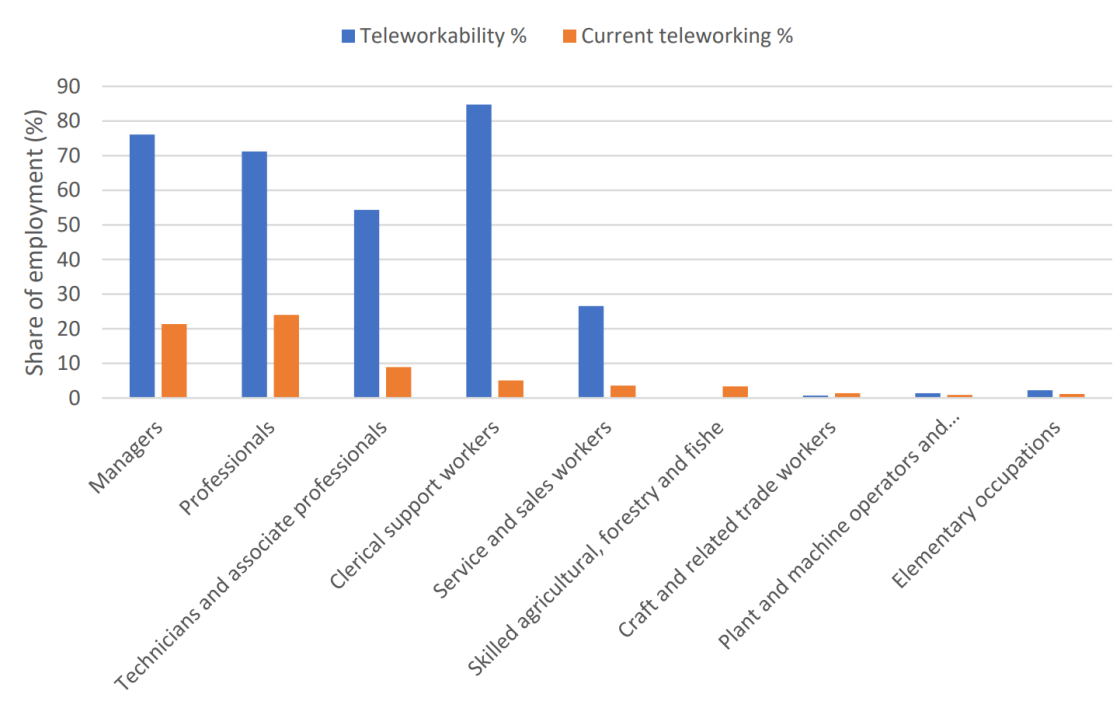

Pre-pandemic, flexibility was mostly enjoyed by high-skilled roles, including knowledge workers, professionals and managers working in ICT, legal, business, administration and science. But beware the hierarchy effect: figures comparing technical teleworkability with actual uptake of telework suggest that pre-pandemic telework was driven more by organisational hierarchy and status than by technical feasibility (Figure 3).

Figure 3 : Prevalence of telework by occupation, EU-27

Source: JRC121426.

Task-based flexibility will get you further

Measures that classify entire roles as non-teleworkable underestimate the full potential of hybrid working. A teleworkability index developed by JRC/Eurofound, for example, uses task-level variables to determine teleworkability, and classify jobs as “non-teleworkable whenever any of these indicators is above a certain threshold, and as technically teleworkable otherwise.”

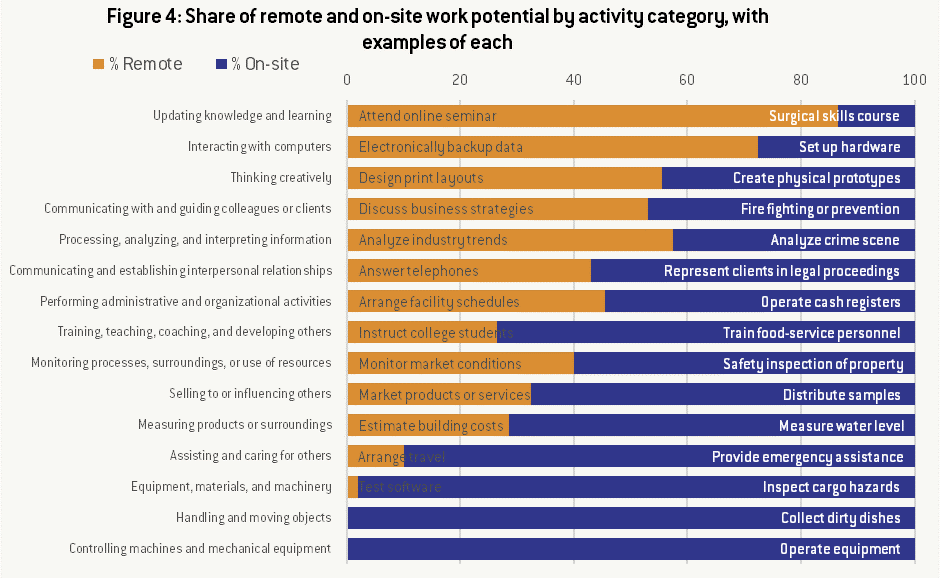

A focus on the task composition of each role and what share of those can be performed remotely or asynchronously will enable firms to offer flexibility to a greater number of employees. An analysis of 2,000 tasks across 800 jobs found that ‘updating knowledge and learning’ has the most potential for remote work with an estimated 87% percent of time that can be spent remotely, while ‘assisting and caring for others’ can only be done remotely 10% of the time (making travel arrangements can be done remotely, for example, but providing emergency assistance cannot) (Figure 4). ‘Handling and moving objects’ and ‘controlling machines and mechanical equipment’ were found to be impossible to do remotely (with a score of 0) but innovation will likely change that as drones and other remote technologies become more widely used in factories.

Source: Bruegel based on McKinsey Global Institute (2020). Note: Bars contain examples of tasks than can (yellow) and cannot (purple) be done remotely.

Preference-based flexibility for greater engagement

Whenever structural aspects allow for flexible working, employers can boost employee engagement insofar as it meets workers needs’ and preferences, by taking into account personal wishes or ambitions (such as coaching for junior staff), personal circumstances (such as chronic illness, commuting time or care work) and personal characteristics (like personality, tenure and age). Teams could even redistribute tasks across people according to their flexibility preferences.

Challenge 2: Designing an optimal configuration of flexibility at the collective level

Once the potential for flexibility is known at individual and task level, companies face the challenge of finding an optimal level of flexibility for the organisation as a whole. In a context of interdependent tasks, insights into the externalities arising from individual flexibility can steer coordination efforts within teams and departments.

Two tasks are interdependent when the value of performing one task depends on the way another task is performed. Assembly-line work is obviously highly interdependent: when one task in the line is not performed correctly or on time, all subsequent tasks suffer. But knowledge work can also be highly interdependent: when research assistants miscalculate data, professors may draw unfounded conclusions in their papers. Interdependence is the foundational concept for determining the boundary and composition of teams and departments. Therefore, in well-designed teams, tasks of team members are highly interdependent.

Coordinating tasks to ensure productive hybrid teams

Research shows that teleworking increases coordination costs: less opportunity for informal coordination (in terms of networking, coaching and one-on-ones) increases the need for formal coordination (more time spent on meetings, calls, or answering e-mails). This increased coordination cost reflects the presence of task interdependence which, in a hybrid context, needs to be investigated through two additional lenses: spatial and temporal.

A journalist writing an article and a copy editor reviewing the text are examples of two purely temporally interdependent tasks. The tasks can be performed remotely without loss of value but as time passes, the news story becomes less relevant and the combined value of the tasks decreases. In this case, the two workers should synchronise their working time.

However, two engineers producing parts of a physical prototype work on spatially interdependent tasks. While they can work at different times, their work needs to take place in same location to ensure proper fitting of the parts.

This need to coordinate work on-site or in time can be facilitated by team or organisational guidelines. The highest level of interdependence can be found within teams making them a good place to start discussions on aligning flexibility. Most predictions settle on a 60/40 or 40/60 division of remote/onsite work. Depending on their specific needs, teams can spatial and temporal needs by agreeing on fixed (weekly) office days and minimum availability during regular office hours.

Preventing the breakdown of distant networks to sustain innovation

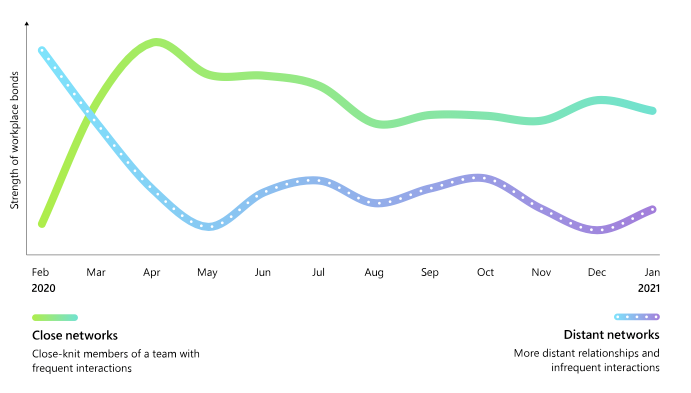

Given the high level of task interdependence within teams, it is unsurprising that team interactions moved online when in-person meetings were no longer possible. An analysis of 124 billion emails and video calls showed an increase in online interactions within close networks or teams (Figure 5). However, interactions across teams took a nosedive, leading researchers to conclude that “teams are more siloed in a digital work world”.

Figure 5: Interactions increased in close networks, but decreased in distant networks

Source: Microsoft Work Trend Index.

This decrease in communication across distant networks is especially concerning for innovation. The creativity benefits flowing from networks of weak ties (interpersonal connections between sporadically interacting people) have been documented extensively following Granovetter’s (1973) strength-of-weak-ties theory (see for example Baer 2010). While employees with weak ties are probably not very task interdependent, they often are knowledge interdependent, meaning “the value they could generate from combining their knowledge differs from the value they could obtain from applying their knowledge separately”. It is not uncommon to hear that the best ideas arise over coffee and that the watercooler is the best place to informally exchange information.

To ensure that innovation isn’t hindered by hybrid working, companies must prevent the breakdown of weak ties and support spontaneous interactions across teams. Just like fixed weekly office days for teams, departments could have fixed monthly office days. At minimum, organisations should avoid accidentally preventing cross-team exchanges by assigning different office days to different teams. Structurally, companies could instate cross-team guilds or rotate people across project teams to grow weak-tie networks. Finally, organisations could support spontaneous cross-team interactions by moving them online (using applications like RandomCoffee) or by making the office an attractive place for meeting and socialising. Such initiatives can help steer organisations towards well-functioning hybrid models.

Recommended citation:

Nurski, L. (2021) ‘Designing a hybrid work organisation’, Bruegel Blog, 5 July

This blog was produced within the project "Future of Work and Inclusive Growth in Europe", with the financial support of the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth.