Private equity and Europe’s re-capitalisation challenge

Companies are struggling in the coronavirus crisis but solvency support provided by the European Union looks likely to be modest.

The ongoing deep recession is certain to leave in its wake a significant number of corporate insolvencies, once current moratoria on debt service end. The shortfall in corporate capital could be €720 billion, based on the European Commission’s May 2020 baseline economic scenario.

The Commission put forward proposals for broad-based EU support for corporate equity but, in an effort to reduce the overall size of the bloc’s 2021-2027 budget, the European Council in July essentially rejected these. The Council completely de-funded a grant-based solvency instrument, which was to amount to €300 billion. Funding of InvestEU, the successor to the ‘Juncker Plan’ of 2015, was cut from a proposed €34 billion to €5.6 billion (based on the provisioned value of an EU guarantee which would be leveraged in the capital markets). This will curtail the private-sector investment activities of the European Investment Bank Group and by other public-sector implementing partners. Financing for SMEs will be especially hit.

The ongoing deep recession is certain to leave in its wake a significant number of corporate insolvencies, once current moratoria on debt service end

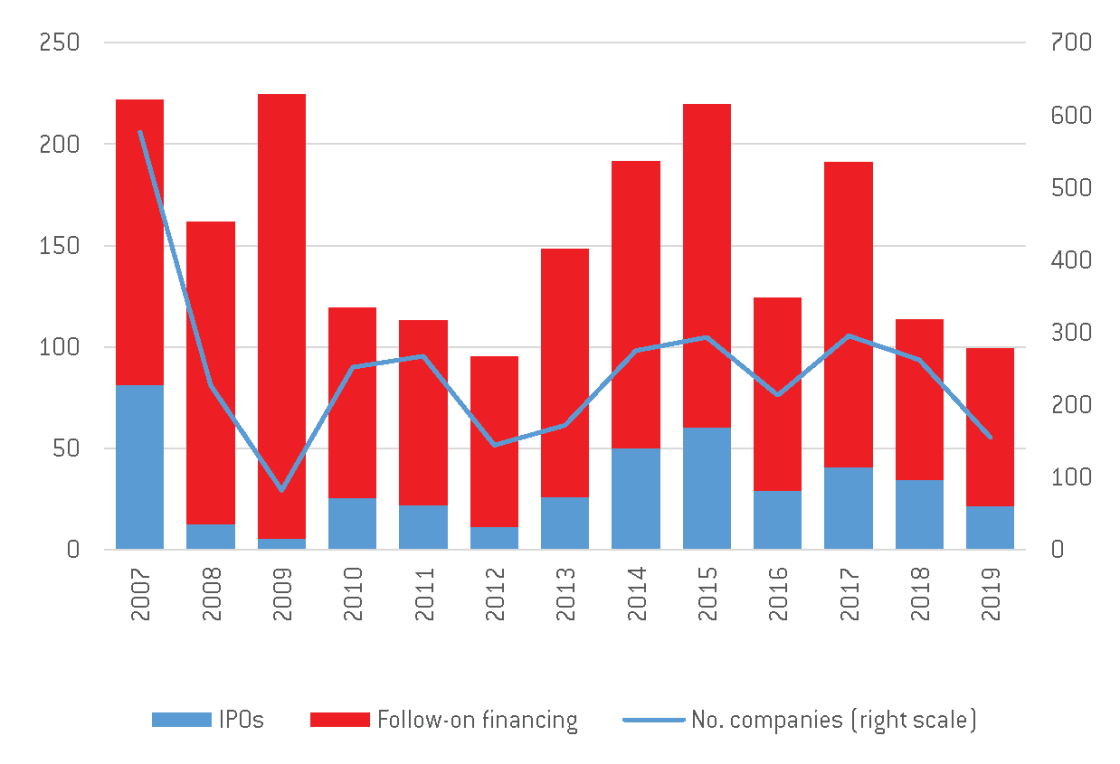

Can private equity go at least some way to picking up the slack? Equity funding has steadily shifted from stock exchanges to private transactions (Figure 1). Recent figures show that in the three years to 2019, European private equity funds raised €309 billion, and invested €254 billion. This compares to €453 billion in equity issuance on European exchanges over the same period, of which roughly two thirds was secondary offerings by firms that had previously listed. In 2019, private equity investment (€94 billion) was roughly level with equity financing on primary markets (€99 billion in IPOs and follow-on financing). This shift from funding on public markets to private transactions is a global trend, and compared to the EU has progressed even further in other advanced capital markets, such as the United States. It is explained by a search for yield by institutional investors, which are given more scope to allocate portfolios into illiquid assets, a corporate sector in which intangible assets have become more significant, and by the regulatory costs of maintaining a public listing.

Figure 1: Equity financing in Europe

|

IPOs and follow-on financing (€ bns) |

Private equity investment (€ bns) |

|

|

Source: AFME and Invest Europe. Private equity investment refers to both initial and subsequent financing of investee companies. Both public and private equity financing are before reflow (ie share buy-backs, or private equity exits).

A realistic contribution from private equity investors

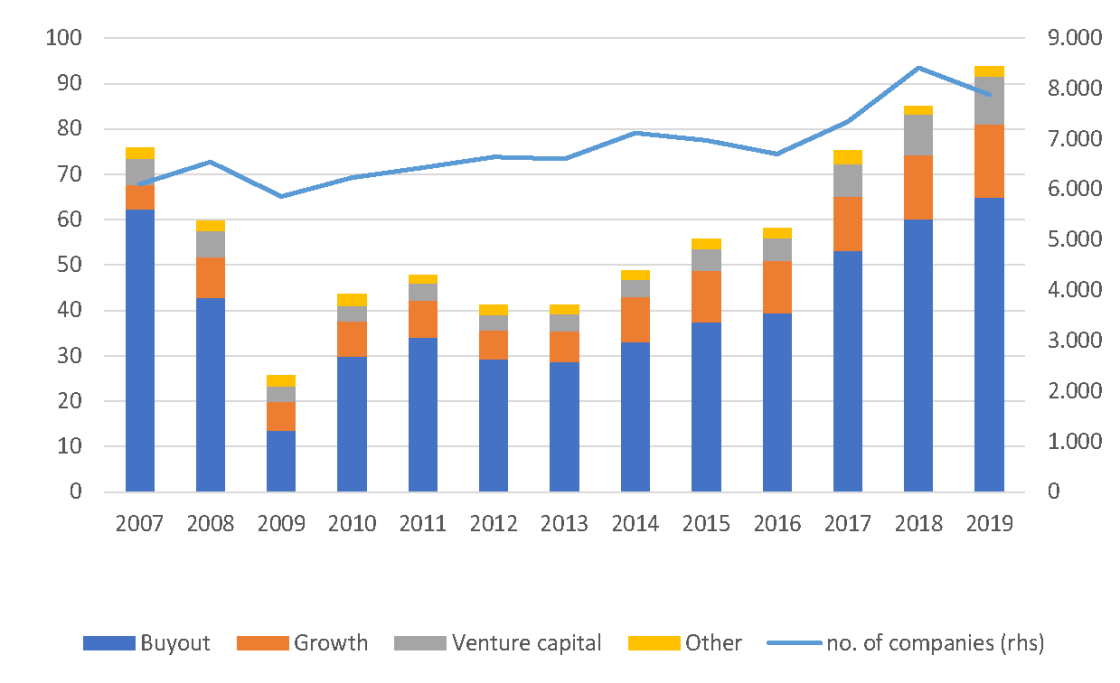

The structural shift towards private equity financing creates opportunities to address the post-crisis capital shortfall, and the required repair of corporate balance sheets. In 2019 alone, European PE investment was directed to about 7,900 companies, 84% of which were SMEs. Globally, the industry is estimated to have available $2.5 trillion in so-called ‘dry powder’ of uncalled capital (and $830 billion for buyouts alone).

At the same time, the business model of this industry will to a great extent limit potential investments to firms with clear growth prospects. This is because private equity funds target companies with established records of growth and profitability, where investor engagement rapidly yields efficiencies, and where modest valuation allows a profitable exit within about five years. The bias towards promising portfolio companies, enhanced funding, and deep engagement by the fund in operational management has been shown to result in significant improvements in innovation, productivity and competitiveness (see for example this survey of empirical studies), including in the less-developed EU capital markets. Investment in firms that already suffer from debt distress is very limited, though it happens when funds initially acquire non-performing loans.

The structural shift towards private equity financing creates opportunities to address the post-crisis capital shortfall, and the required repair of corporate balance sheets

Thus, the industry will only partially fill the gap left by the less-ambitious InvestEU. Market failures in SME equity financing arise primarily because companies are too small and lack transparency, and because of poorly developed local investor bases and supporting market infrastructure.

Also, private equity is controversial in many EU countries: there is a sharp focus on profit to align managers’ incentives with those of owners. Private equity owners with portfolios of SMEs might be more tolerant of insolvency in an individual firm than an owner-entrepreneur would be.

The closed-end funds present few systemic risks from liquidity mismatches or leverage at the level of the fund itself. But the often aggressive use of debt in investee companies through a complex structure of holding companies presents a different picture. Leverage boosts returns to equity investors and utilises the tax shelter commonly offered for debt service costs. It also acts to discipline managers of investee companies. European Central Bank analysis showed that private equity-controlled companies account for 80% of the European leveraged loan market, and represent a greater credit risk than the rest of the high-yield investment universe.

Ironically, despite the thorough due diligence done by investment funds, many private equity-controlled companies are categorised as being in financial difficulty under the General Block Exemption Regulation and hence ineligible for state-guarantees. A rapid expansion of the industry would raise financial stability concerns. The ECB already in 2017 limited bank lending to such private equity-owned firms. EU state aid rules on this sensibly remained unchanged in the March 2020 Temporary Framework for state aid.

An agenda to support private equity financing in the recovery

Nevertheless, private equity funds will now play a crucial role in securing funding for growth companies. Over the medium term, reforms could boost EU private equity investments, which, relative to GDP, remain less than one third of those in the United Kingdom or US. A more joined-up approach to regulation and policy at national and EU level would be needed:

- First, funding of private equity will need to become more integrated across the EU. Funding is overwhelmingly national, with EU capital from outside the fund’s home base accounting for only roughly one fifth on average in the EU pre-Brexit (this segmentation is even starker for venture capital). Many smaller EU countries have very limited local capacity to deliver private equity. Segmentation of funding is due to the local presence required for fund managers in due diligence and investment management, and will affect in particular smaller or underdeveloped markets. Proposals that could bridge cross-border information barriers would be especially helpful – for instance the idea for a single access point for firm financial and sustainability information, as set out by the High-Level Forum on the Capital Markets Union.

- A related challenge is the UK, whose investors account for roughly half of funds raised in Europe and of assets under management. As passports for cross-border activity lapse, the extensive delegation arrangement with fund managers in the UK will come under review. A third-country regime for professional investors should be activated. In the meantime national supervisors should establish cooperation agreements with their UK counterparts.

- A further objective should be transparency and disclosure standards that will ultimately allow a greater range of investors to access private equity investment and other alternative assets. As fund managers act as agents for professional investors, standards of disclosure vary and scrutiny is less than that for banks, for example. Unlike in the US, where defined contribution pension plans can now invest in private equity, the distribution of such funds to retail investors and pension plans within the EU is heavily restricted. Transparency and disclosure of environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance needs to be strengthened to attract such investors.

- Finally, as governments expand the equity investments by their national promotional banks and local funds, private fund managers could be involved to lend expertise, for instance in fund-of-funds structures.

These aspects should now be considered in the upcoming review of the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD). The drafting of this directive in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis was heavily influenced by the perceived risks of hedge funds, which are lumped into the group of professional investment firms covered by the directive alongside private equity firms. A June 2020 report by the Commission acknowledged inefficiencies arising from inadequate passporting rights and lack of cross-border distribution of smaller funds. It also noted that individual authorities adopt overly onerous standards.

As in other advanced jurisdictions, EU private equity has so far remained in the shadows of the financial system and has been lightly regulated. The past increase in financial system leverage has led to some questionable investment practices. The revised AIFMD should now seek to open up private equity to a wider set of investors and to integrate EU markets, while addressing concerns around financial stability, corporate governance and disclosure.

Recommended citation

Lehmann, A. (2020) 'Private equity and Europe’s re-capitalisation challenge', Bruegel Blog, 17 September