Inflation targets: revising the European Central Bank’s monetary framework

The ECB is looking to evaluate whether its definition of price stability is effective in helping anchor inflation expectations. We argue that the curr

The toughest job central banks face in the next five years is managing uncertainty. In the euro area, inflation is persistently low and the ammunition available to raise it is minimal. Meanwhile, structural changes, including the rise of the digital economy and its effects on productivity, and the threat to global open trade, imply that we do not know how the economy will work. At the very least, the European Central Bank (ECB) will have to design policy not just for specific circumstances but for as many circumstances as possible.

The first guiding principle in revising the ECB monetary policy framework should be to reduce the degree of uncertainty the bank itself brings to the system. In other words, the ECB policy framework should be clarified to minimise self-generated policy uncertainty, and the starting point here will be to have a clear focal point to anchor expectations of inflation.

We propose two changes to ensure that the ECB’s inflation target acts as such a focal point. For any inflation target to be an effective focal point, it requires two things: the target needs to be clear for all to understand and it needs to be implemented in a framework in which it can be assessed.

The current numerical objective communicated by the ECB is “below but close to 2%”. This is not as precise as it could be. The word ‘below’ suggests that there is a downward bias in the definition, which might make current conditions more difficult to escape from. By contrast, the word ‘close’ suggests that the ECB might actually be targeting implicitly a lower level of inflation, say 1.8%. And there would then be no downward bias, because the ECB might be targeting inflation symmetrically around that smaller number. But it is not clear which one is true and there is no benefit from adding disagreement to the ECB’s definition of price stability. The first step to achieving a focal point would be to change the mandate to read “the inflation objective is 2%”.

However, this is not enough. Inflation (at the relevant horizon) will never be at exactly 2%, implying the ECB can never hit its target. What is needed is a band around 2% that would provide meaningful information in terms of what is tolerated. If the band is too broad, the target would again become meaningless, because it would mean any number is tolerated. But too-narrow a band (and at the limit a specified number) and the signalling value of the inflation target would also disappear because inflation will seldom fall within these narrow limits.

An inflation target becomes meaningful if there are appropriate bands around it. would allow Agents would then observe the inflation outcome and evaluate whether the central bank has been successful or not. A few successes and the central bank would become credible, meaning expectations are anchored to the numerical target. A few failures and expectations could become de-anchored. Importantly, credibility is itself the outcome of performance, and constrains or assists the central bank in achieving its goal.

What qualifies then as “appropriate band width”? This depends on the level of uncertainty in which Central Banks operate. If uncertainty is high, then inflation is less likely to land in tight bands. The Central Bank ends up being seldom successful. If uncertainty is low, broad bands risk blurring the signalling quality of the target. The Central Bank risks unnecessarily failing to convince agents to anchor their expectations on the target.

Most Central Banks that have an explicit inflation target also apply a band around it, although not all do (that includes the US Federal Reserve Bank as well as the ECB). Those that do have bands around a 2% inflation rate (including the Bank of England, Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Riksbank) tolerate a variation in inflation between 1% and 3%. The Reserve Bank of Australia targets inflation between 2% and 3% and has a tighter band around the mid target of 2.5%.

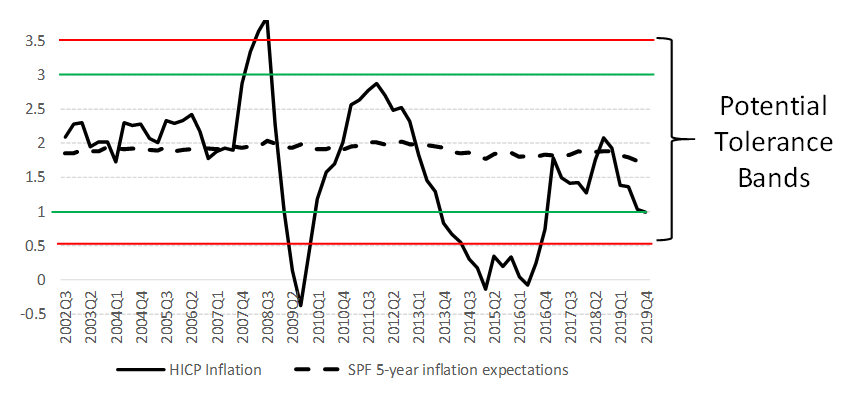

Figure 1: Euro-area inflation and inflation expectations (%)

Source: ECB, HCPI inflation and SPF 5- year ahead inflation expectations. Quarterly HICP inflation rate based on year-on-year monthly inflation.

The ECB is going to have to operate in conditions of high uncertainty. What might have therefore been an acceptable tolerance band between 1% and 3% percent in earlier years, might no longer be enough. The ECB should define what it is prepared to accept. For example, negative inflation might not be acceptable, and it is unlikely that any inflation above 4% could be justified as a temporary shock. This should form a basis for the ECB to feel confident to commit to an inflation band of between 0% and 4%. This looks rather wide, especially in the context of the euro area’s inflation history since 2002 (Figure 1). An inflation target of 2% with a tolerance band of between % could be more effective to provide a meaningful signal, while allowing for the fact that the inflationary path is riddled with uncertainties.

Recommended citation

Demertzis M. and N, Viegi (2020) 'Inflation targets as focal points: Revising the European Central Bank's monetary framework', Bruegel Blog, 20 February, available at https://bruegel.org/2020/02/inflation-targets-revising-the-european-cen…