China’s debt is still piling up – and the pile-up is getting faster

With looser monetary policy, China's policymakers hope to encourage banks to lend more to the private sector. This seems to imply a change from the de

If you think China’s monetary policy became more lax in 2018, wait for 2019. Pushed by gloomier activity data, China’s policymakers have moved from an orthodox monetary policy to a much more heterodox one.

The core of this more aggressive move is to exhort banks to lend more to the private sector, with specific targets on the amount of credit granted to private companies and, in particular, small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Such a move is clearly costly for banks, as private companies tend to be more leveraged and/or less able to repay debt.

China’s Version of Quantitative Easing

This explains why the People Bank’s of China (PBoC) has decided to facilitate the banks’ task in two ways: first, by providing cheaper liquidity to banks lending to the private sector; and secondly, by facilitating banks’ efforts to increase their capital base. In fact, with what could be considered a very bold move, with some resemblance to the quantitative easing of major central banks globally, the PBoC has announced that it will acquire (or more precisely, swap for three years) the perpetual bonds that Chinese banks’ will issue to beef up their capital.

While all of this should be good news for China’s growth in the short term, it also implies that the private sector—which is now credit constrained—will regain access to bank credit and therefore will be able to leverage even further.

This is clearly a worrisome development, as it seems to imply that the Chinese authorities will be turning away from the deleveraging drive that they started in mid-2017, when they considered China’s debt level to be excessive.

Where is the Debt Piling Up?

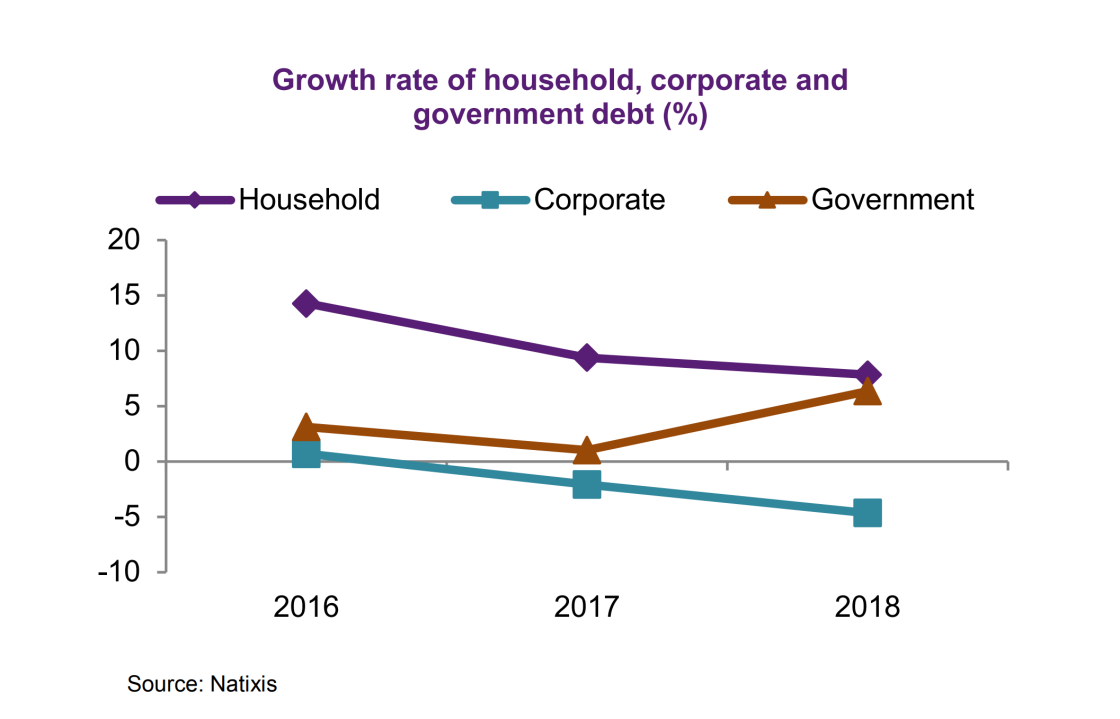

Against this background, it’s important to assess how leveraged China really is, and which sectors of the economy are the most indebted. Real leverage can be understood as the debt levels of the public, corporate and household sector. In a recent analysis conducted by Natixis Asia research, we have developed our own debt estimates of China’s real economy by sector.

One of the advantages of our estimates is that they are more timely than those published by international organizations or China’s official statistics. A second advantage is that it reclassifies the debt incurred by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) into public rather than corporate debt, so as to have a better sense of the dynamics of China’s public debt.

Corporate Debt is Falling

Based on our estimates, China’s total debt continued to grow in 2018, but in a milder way than in the past. In other words, China’s real economy has not stopped leveraging, but it seems to be calming down for the time being. Interestingly enough, the key contributor to the deceleration in leverage is the corporate sector, which has long been the key worry of China watchers. Corporate debt fell from 134 percent in 2017 to 128 percent in 2018.

The reduction in corporate leverage in 2018 comes hand in hand with much stronger pressure by the leadership since mid-2017, which has pushed companies–especially those dependent on shadow banking–to deleverage and even divest assets.

Household Debt is Growing

Household debt, on the contrary, grew rapidly in 2018. The surge mainly came from the expansion of mortgage debt stemming from the property market and rising credit card consumption. Based on the gradually stabilizing housing market and rapid increase in household income, we believe the risk is under control so there is still limited systematic risk arising from this sector.

In addition, public debt also surged during the year, mostly due to on-balance-sheet local government debt. The difficulty that local governments encountered accessing shadow banking and the committed expansion in infrastructure investment both contributed to the fast increase. However, consistent with our fiscal analysis, both central government debt and off-balance-sheet local government debt (LGFV) have increased only slightly.

No Crisis Yet

If we combine the three sectors, China’s total debt to GDP has moderated its increase in 2018.

What’s more, most of the reduction is related to the clampdown in shadow banking, which has limited the financing ability of private companies, especially those that have been forced to divest assets. On the other hand, other sectors have continued to leverage. This is particularly true for the public and the household sectors.

That said, we do not expect the debt problem to pose any crisis-level threats. China’s nominal growth is still high, keeping the debt-to-GDP ratio relatively stable. Also, the cost of funding remains low and is under the control of the PBoC since the capital account is not fully liberalized even, with a managed exchange rate. Another plus for China’s debt sustainability is that only a very limited share of China’s debt is external (around 10 percent of GDP).

Still, even ruling out a debt or financial crisis, China will not be able to avoid the consequences of an over-leveraged economy. China’s piling up of debt cannot but imply deflationary pressures and a lower potential growth down the road as it drags down consumption and investment.