The EU - Japan Economic Partnership Agreement

This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on International Trade (INTA) and analyses the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement

This study was requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on International Trade. The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. The study is available on the European Parliament’s webpage. © European Union, 2018

The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EUJEPA) is the largest bilateral trade deal ever concluded by the EU in terms of market size, covering close to 30 % of global GDP. It includes commitments not only on trade in goods but also services and the promotion of bilateral investment. Moreover, it contains the most up-to-date EU provisions on corporate governance, the mobility of natural persons for business and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) protection, including trade secrets. As such, it represents the joint efforts of the EU and Japan to develop models for new generation trade agreements.

According to the latest DG Trade estimates (European Commission, 2018), the impact of the agreement is expected to be balanced, with considerable gains for the EU in sectors such as agri-food, textiles and leather products. No EU sector would experience a significant loss. Overall, EUJEPA is expected to increase the EU’s GDP by 0.14 % and total exports to Japan by EUR 13 billion by 2035. The main purpose of our study is to evaluate these main conclusions of DG Trade.

There are several reasons for the trade agreement between the EU and Japan. The decline of Japan’s share of the EU’s goods exports (from 6.9 % 1990 to 3.2 % in 2017) and likewise the share of Japanese goods in the EU’s import basket (from 12 % in 1990 to 3.7 % in 2017) was a source of bilateral concern1. Currently, Japan is also not a major destination for European investment abroad, representing only 1.1 % of total extra-EU outward stock in 2016. The EUJEPA was therefore considered a strategic priority to revitalise trade and investment with Japan and expand opportunities for EU producers in the fast-growing Asian continent under the EU’s Trade for All strategy launched in 2015.

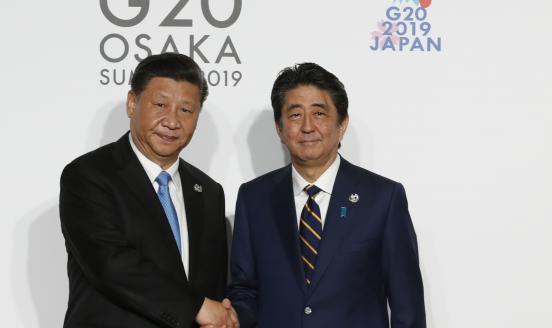

The EU-Japan agreement has gained heightened geopolitical importance following the suspension in 2017 of talks between the EU and United States on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), and the imposition by the US in June 2018 of a 25 % tariff on steel and 10 % tariff on aluminium products. EUJEPA provides a major platform for both the EU and Japan to reinforce their commitment to rules-based trade and deepen their alliance against unilateral and protectionist policies. For Japan, the trade deal is an integral component of so-called third arrow (structural reforms) of ‘Abenomics’. On 6 July 2018, Japan also ratified the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP-11), the successor to the TPP agreement, from which the US withdrew in January 2017. This agreement will unite 11 Asia-Pacific countries covering 13.5 % of global GDP2 in a multilateral free trade zone. As well as Japan, Mexico and Singapore also ratified the agreement in April and July 2018 respectively. The agreement will enter into force 60 days after ratification by at least six of the eleven signatories. When implemented, the CPTPP-11 is expected to improve the competitiveness of Japan’s economy by reducing the cost of sourcing intermediate inputs from partner countries. As a result, Japan’s exports to the EU would increase as well (Felbermayr et al, 2018).

The impact of EUJEPA will also be affected by the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU in March 2019 in significant ways. Japan’s total exports to the UK amounted to EUR 15.1 billion in 2017 (equivalent to 17 % of Japan’s exports to the EU) and imports from the UK to EUR 16.8 billion (equivalent to 18 % of Japan’s imports from the EU). Moreover, Japanese companies have invested heavily in the UK, as shown by their FDI position (with immediate ownership) of GBP 46.5 billion in 20163. This investment strategy was mainly aimed at gaining access to the EU’s single market. After the transition period for the UK leaving the EU ends in 2020, Brexit will reduce the market size for Japanese goods and services under the EUJEPA and affect the production operations of Japanese companies. On the EU side, the EUJEPA provides an additional source of external demand to partially counter the adverse effects of potential new trade frictions following Brexit, such as differences in tariffs, increase in customs procedures at the border and meeting rules-of-origin requirements.

In terms of historical timeline, the European Council gave the European Commission the mandate to start negotiations with Japan in November 2012. The first round of negotiations was held in April 2013. Following 18 rounds of negotiations, the parties reached a political agreement on 6 July 2017. The text of the agreement was finalised in December 2017 after which the Commission submitted it to the Council for approval in April 2018. The Council authorised the decision to sign the EPA and requested the consent of the European Parliament on 6 July 2018. The agreement was then signed on 17 July 2018 at the EU-Japan Summit in Tokyo. In terms of transparency, the negotiating directives, reports of negotiating rounds and finalised legal text were all published online by December 2017. Thematic factsheets, case studies of exporters and impact assessment reports were shared, and civil society dialogues and general meetings with the EU Trade Commissioner were held to increase public understanding and participation in the issues involved.

In advance of its final plenary vote on the agreement, the European Parliament therefore commissioned an independent Bruegel study on the topic. The study is structured as follows: Section II provides descriptive statistics on the trade and investment relationship between the EU and Japan. Section III gives a concise overview of the substantive provisions of the EUJEPA. In Section IV, legal texts from the family of the EU’s new generation trade agreements (EUJEPA; the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, CETA; the EU-Singapore Free Trade Agreement, EUSFTA; the EU-South Korea Free Trade Agreement, EUKFTA) are compared in detail by studying WTO+ and WTO-X provisions. In Section IV, we use recent statistics to compare the EU’s trade with Japan with the composition of EU trade with Canada, South Korea and Singapore. In Section V, we assess the economic and social impact of the agreement by reviewing the literature that utilises CGE and NQTT methods to estimate the impact of the EUJEPA. We highlight where these projections overlap or diverge with the actual outcomes observed after the implementation of the EUKFTA. Using detailed information on revealed comparative advantage and tariff schedules, we highlight potential areas of opportunities and threats for the EU. Finally, in Section VI we examine the framework for implementing the provisions of this trade deal and flag issues of concern. Section VII concludes our analysis with policy recommendations.