The Republican Tax Plan (2): The debate rumbles on

Reactions to the Republican tax plans continue, concentrating on different aspects of the proposed legislation. We review the latest contributions.

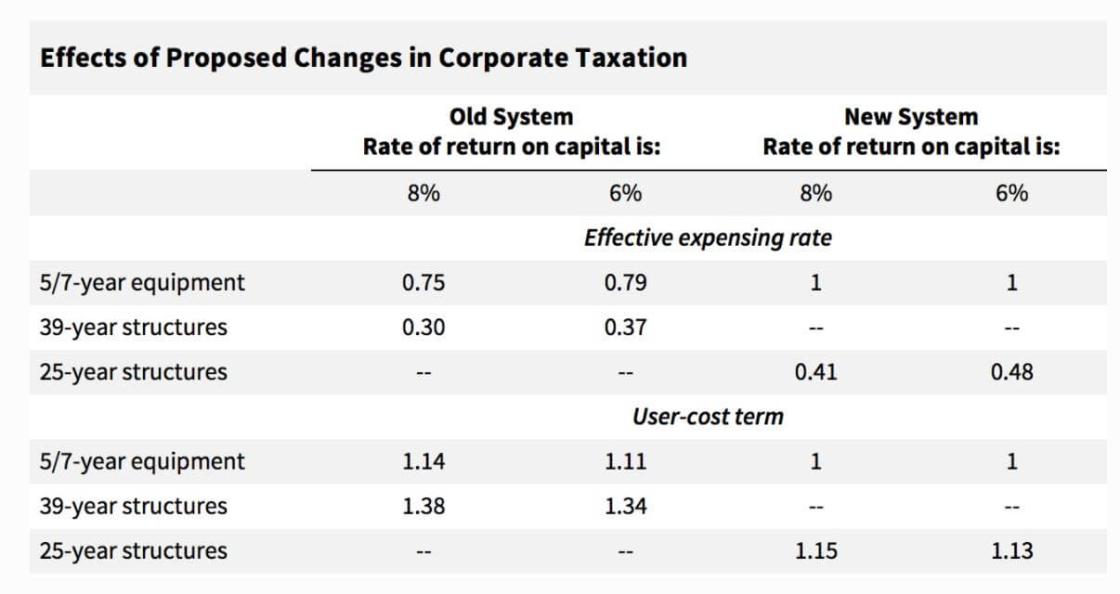

Robert Barro writes on Project Syndicate that by reducing the costs of investments and cutting the tax rate on corporate profits, the final plan that emerges will likely boost growth substantially. His conclusion is based on three likely changes to the taxation of businesses (which he treats as permanent, in his analysis): (i) a reduction of the main tax rate on profits of C-corporations from 35% to 20%; (ii) a replacement of the current system of depreciation allowances for new equipment with immediate 100% expensing; (iii) the shortening of the recovery period for most non-residential business structures, such as office buildings, from 39 to 25 years.

Barro uses two complementary approaches to estimate impacts on investment and economic growth. The first method starts by gauging the effects of the tax-law changes on the costs that businesses attach to investment in equipment and structures. Then he estimates long-run responses of the capital-labour ratio to the changes in user costs. His calculations suggest that the growth rate rises in the short run by 0.34% per year – and after 10 years, the level of real per-capita GDP is higher by 2.8%, implying that the average growth rate is higher by around 0.28% per year over a ten-year span. The estimated increase in long-run real per-capita GDP would be around 7%.

Source: Barro

Martin Feldstein argues that cutting US corporate tax is worth the cost. Feldstein estimates that the total increase in capital in the corporate sector over the next 10 years will reach at least $5 trillion. The increased flow of capital to the corporate sector will raise productivity and real wages. If that happens, it will raise annual real GDP in 2027 by about $500 billion, equivalent to 1.7% of total 2027 GDP, implying a gain of $4,000 per household in today’s dollars. One of the main criticisms leveled at congressional Republicans' proposal to cut corporate taxes is that a higher budget deficit would amount to an undesirable fiscal stimulus. Feldstein disputes this criticism pointing out that with monetary policy turning contractionary, and most experts predicting a US recession in the next five years, stimulus should be welcomed; he also dismisses the crowding-out argument by saying that although the $1.5 trillion of government borrowing caused by the tax bill during the next decade could crowd out an equal amount of private borrowing, the capital stock will grow by an even larger amount. The $1.5 trillion corporate tax cut will go directly to US companies, and the stock of corporate capital will grow further because of the inflow of funds from the rest of the world.

Jeffrey Frankel states that while the US has plenty of experience with irresponsible tax cuts, its leaders seem not to have learned their lesson. Recalling what transpired under Reagan might shed some light on the Republicans’ murky current proposals. There were two tax bills during the Reagan years – the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 and the Tax Reform Act of 1986 – and they differed in almost every respect. The 1986 reform was a model of how to carry out fiscal reform, whereas the 1981 process was a model to avoid. Yet it is the latter that the Republicans’ current tax “reform” most resembles. Reducing the US corporate income tax rate would be a good move, provided that the lost revenue were recouped through the elimination of business loopholes, such as the corporate interest deduction and the favored treatment of carried interest. But the legislation cuts the corporate tax rate too much and closes too few loopholes to achieve anything close to revenue neutrality.

Frankel thinks there is good reason to fear serious long-term consequences of the rise in the budget deficit, owing to two key issues of timing – one cyclical and the other demographic. The 1981 tax cuts went into effect at the onset of the 1981-1982 recession, a time when some short-term fiscal stimulus came in handy. The opposite is true today. Moreover, the baby-boom generation is now retiring at a rate of about 10,000 people per day, meaning that Medicare and Social Security outlays will increase rapidly. Meanwhile, the national debt held by the US public stands at 76% of GDP, compared to just 25% when Reagan took office. In short, this is the wrong time to be increasing the budget deficit and borrowing more – particularly with interest rates set to rise further.

Lawrence Summers argued that the Senate GOP tax plan would cause ‘thousands’ to die. His claim is mostly based on work by Kate Baicker, dean of the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, who performed two studies on the impact of being insured on mortality by looking at the effect of moving from uninsured to insured. Some may argue that any loss in health care, resulting from a repeal of the Affordable Care Act's mandate to insure, is voluntary - and that families should have the freedom to make choices about optimal health coverage. But Summers thinks this ignores two realities. First, for many, the loss of health insurance will not be voluntary: they will lose coverage because premiums will increase, pricing them out of the market. Second, the insights of behavioral economics suggest that irrational actors may make choices that will lead to worse health outcomes and higher mortality rates.

Casey B. Mulligan and Tomas J. Philipson disagree with Summers, arguing his argument is mistaken in several ways. First, if the tax bill reduces federal programme participation, it is simply among people who were only on the programme in the first place because the Obama administration forced them to buy health insurance that they do not like or want. Standard economics predicts that people are better off when they make choices voluntarily and even if behavioral biases were the primary factor to consider, they support decentralised – rather than centralised – decision-making. Second, there is little and poor evidence linking insurance coverage to mortality, thus the studies in medical journals cited by Summers are cherry-picked. Third, Summers argues potentially higher premiums may prevent consumers from attaining affordable coverage – but these predicted premium effects are speculative, especially given how poorly the profession predicted the premium impacts of Obamacare itself. Fourth, the mandate may in fact be elevating death rates in some populations. Most important, Mulligan and Philippon argue that he tax plan will stimulate economic growth, and economic growth saves lives, particularly so for the poor.