China's rising leverage is a growing risk

Worries about the growth in China's leverage are on the rise. Is this growth in leverage sustainable? Alicia García-Herrero finds that the evidence is

This blog post was originally published on Nikkei Asian Review.

Worries over China's rising leverage have been growing, especially since the country's ratio of debt to gross domestic product surpassed 250% in 2016. This figure might appear reasonable when compared with developed countries, especially Japan and members of the European Union, but such a comparison only masks the different reality China faces.

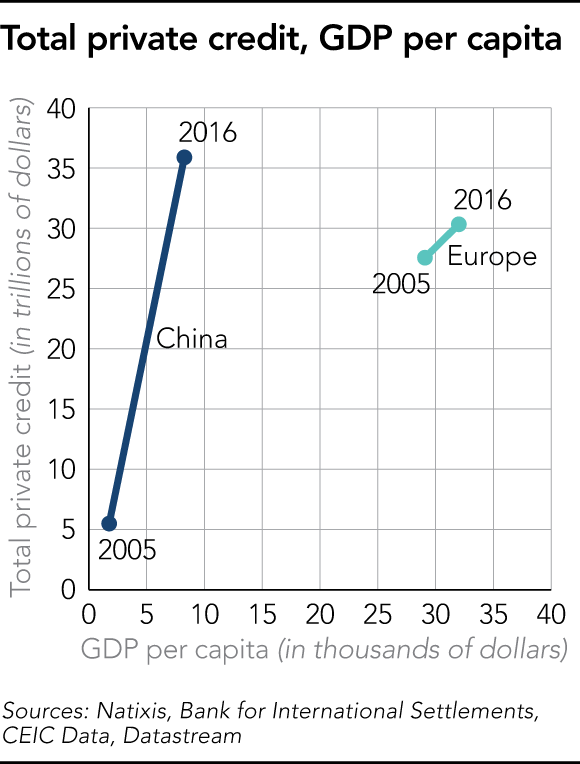

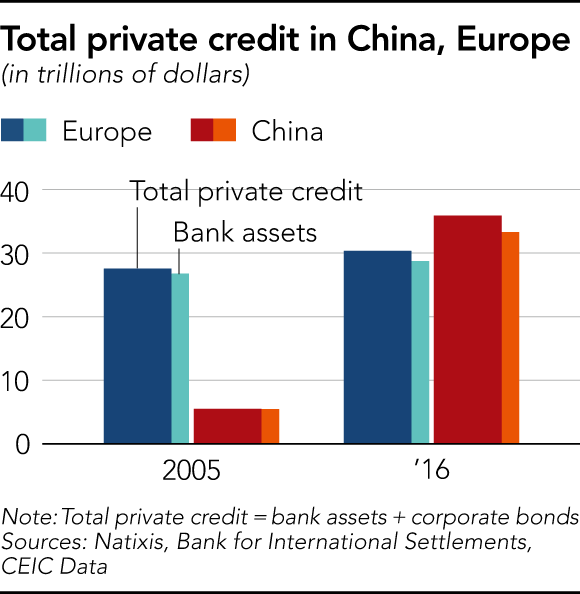

China's GDP per capita is still much lower than that of developed economies, and a good part of its population, as well as many of its small and midsize enterprises, do not yet have full access to credit. Further financial deepening — an increase in the availability and range of financial services — will only increase private credit and, ultimately, leverage.

An easy way to understand where we could be heading in terms of China's leverage is to note that the country's total private credit — as proxied by bank credit and corporate bonds — already outweighs that of the EU. And yet China's GDP per capita is less than one-third that of the EU. A simple extrapolation shows that once China reaches the EU's level of per capita GDP, its leverage will have risen to $100 trillion, but this can only happen over several decades.

So, how sustainable is the growth in China's leverage? While Chinese companies are generally not as leveraged as their international peers, at least in terms of liabilities to equity, a number of warning signals need to be taken into account.

First, by the same proxy measures, leverage is much lower for companies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN companies may be similar to Chinese ones in that they also have more restricted access to deep financial markets than companies elsewhere in the world. However, Chinese companies have a shorter maturity on debt compared to global and even ASEAN peers.

Second, while Chinese companies seem to be less leveraged than their global peers in most sectors, one sector clearly stands out — real estate. Here, leverage is much higher for Chinese developers compared to the global average, and even to the average for ASEAN. This would not be a problem if the sector were small, but that is certainly not the case for China.

The real estate sector accounts for 21% of total Chinese assets, as opposed to an average of 5% for global peers, according to Natixis China Corporate Debt Monitor. The gap in the average maturity between assets in the Chinese real estate sector and in the rest of the world is larger than for other sectors.

SUSTAINED MOMENTUM? This brings us back to the key question: Is a massive increase in corporate leverage sustainable?

China's wide fiscal elbow room and its financial isolation from the rest of the world due to massive capital controls mean the country can support an increase for some time. In the midterm, though, the answer basically depends on how profitable underlying investments will be. So far, the evidence is not very positive.

First, the profitability of Chinese companies, in terms of return on assets, has fallen from above 4.5% in 2009 to less than 2% today, according to a report published by the International Monetary Fund last April, which also cited the persistent issue of overcapacity.

Additionally, Chinese companies' foreign spending sprees especially in Asia — emerging Asia is the largest recipient of foreign direct investment from China — could be an opportunity to increase their return on investment. This has long been the case for Japan, which has obtained a higher return on outward FDI (about 7%, according to Natixis estimates) than on domestic investment (less than 3%).

However, Japanese outward FDI has been mainly of the greenfield type, which involves starting foreign businesses from scratch. China relies more on mergers and acquisitions abroad. It is hard to tell whether the recent purchases by Chinese companies will yield as high returns as Japanese outward FDI, but some of the most recent purchases could raise some eyebrows based on pricing or lack of obvious synergies with the buyer.

In sum, while China's leverage is clearly high and likely to increase further — especially in the corporate sector — it could be justified if the returns on the underlying investments are high enough. The situation clearly differs between sectors but, overall, the return on assets is increasingly low in China and already well below most peers in emerging countries.

Outward FDI may help, but it would have to increase massively as its stock is small compared to China's stock of domestic capital. Emerging Asia should thus expect the tide of Chinese FDI to continue, but from increasingly leveraged corporations, posing a clear risk of contagion in the future.

China's recent M&A spree resembles the behavior of a shopaholic more than a strategic plan. It remains to be seen whether the downward trend in China's return on assets will change and whether that will alleviate the burden of China's leverage issue in the long run. Emerging Asia's increasing dependence on Chinese companies is a new potential channel of contagion for policymakers to take into account.