Codetermination in Germany – a role model for the UK and the US?

The idea of codetermination, i.e. the cooperation between management and workers in decision-making, has grown in popularity lately. We review the cha

Codetermination or “Mitbestimmung” – the German term for worker participation in a company’s decision making – has recently attracted attention as UK Prime Minister Theresa May and US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton promised to strengthen workers’ rights and interests. The latter has called for rewriting “the rules so more companies share profits with their employees”. Mrs May has repeatedly stated her intention to reform corporate governance such that workers and consumers are represented on boards, to “reform capitalism so it works for everyone – not just the privileged few.” Many commentators have interpreted the Brexit vote also as a rejection of the current globalized economic system from which “the rich are gaining at the expense of the poor” (see e.g. here). While codetermination does not only exist in Germany, several authors (see here and here) have wondered whether it could be a role model also for the UK and the US. This blog provides a short overview of the characteristics of codetermination in Germany and evidence from academic literature.

What is codetermination?

Codetermination is deeply rooted in the tradition of German corporate governance and has existed in its current form since the Codetermination Act of 1976. It has an explicit social dimension: as the German Constitutional Court ruled, codetermination on the company level is meant to introduce equal participation of shareholders and employees in a firm’s decision making and shall complement the economic legitimacy of a firm’s management with a social one. Codetermination is therefore about a democratic decision making process at the firm level and the equality of capital and work (Page 2009). Furthermore, according to Kommission Mitbestimmung (1998), the main aims of codetermination consist in making investments in human capital profitable, and “rewarding” employees’ loyalty towards the firm with participation rights.

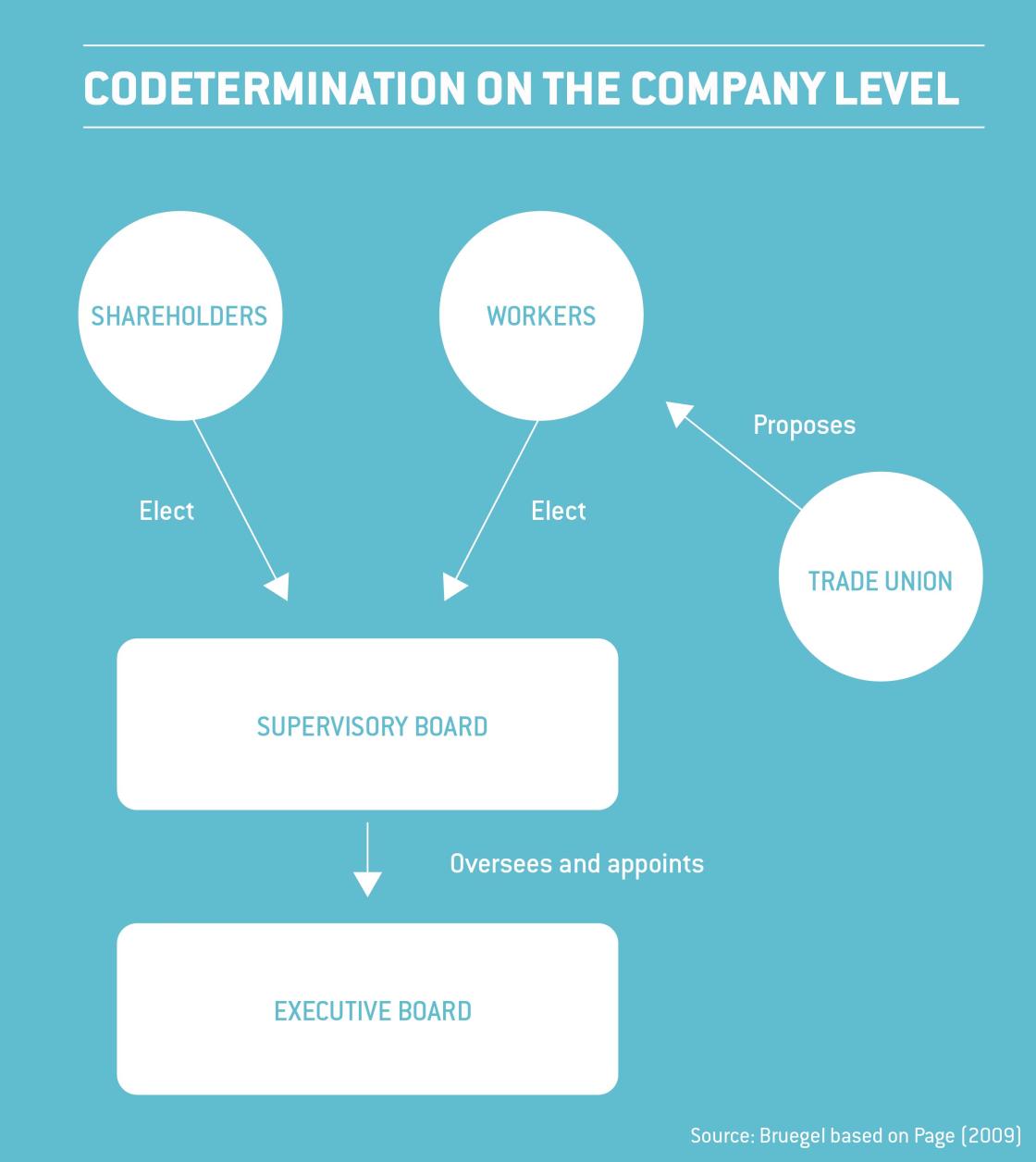

Codetermination could be viewed as an institution enhancing workers’ representation and participation rights in a firm’s corporate governance. There are two levels through which employees are given codetermination rights to participate in a firm’s decision making: the work council (“Betriebsrat”,establishment or “shop-floor” level) and the supervisory board (“Aufsichtsrat”,company level).

The work council is generally elected in firms with more than 5 employees and many of its members are also members of German trade unions. The council is endowed with far-reaching information and consultation rights that enable it to exert influence on working conditions, pay principles, working time etc. Employers must negotiate with the work council if changes affecting the workforce take place, e.g. the dismissal of employees.

Codetermination at the company level, on the other hand, consists in the participation of employees or their representatives in the supervisory board. Germany was one of the first countries to introduce a two-tier system, meaning that the law requires firms to have an executive board, composed by executives and chaired by the CEO, and a supervisory board, composed by non-executives, which are shareholder and employee representatives (including union representatives). Note that workers are thus represented on the supervisory board – not the (executive) board. The number of employee representatives depends on the size and legal type of the firm: one-half of the members of the supervisory board are employee representatives for firms with staff of more than 500 for limited liability corporations (“GmbH”) and more than 2000 for stock corporations (“AG”), and one-third for stock corporations with between 500 and 2000 staff. The chairman of the supervisory board, who is elected by shareholders, has an extra vote in case of a tie.

The supervisory board is generally involved in the appointment of the management board members, monitoring of business operations overseeing the activities of the management board and, in a subcommittee, determining the compensation of its members. With the supervisory board approving major strategic decisions, ultimate corporate power resides with it (FitzRoy and Kraft 2004) and thus also with employee representatives.

Finally, it should be noted that codetermination and wage negotiations are separate as usually unions and employers’ associations bargain with each other. However, there are close personal links between unions and institutions of codetermination as work councillors and thus employee representatives on the supervisory board may be union members (FitzRoy and Kraft 2004).

Codetermination and its effects

Corporate governance is characterized by the interplay between managers and owners of a firm. While the latter wish to maximize the value of the firm in the long run, executives maximize their own utility, for which compensation, prestige, power etc. are relevant. Codetermination introduces a third interest group, employees, to the supervisory board and thus to the firm’s decision making process. The question is whether the interests of each group overlap or are in contrast with each other, and which benefits and costs employee representation entails.

Shareholder vs labour interests, efficiency, and the supervisory board

Some authors have questioned why codetermination should be made mandatory. If it was beneficial, firms would have introduced it themselves and its presence may therefore be inefficient (Jensen and Meckling 1979). There may be rent seeking on part of labor at the expense of shareholders. Indeed, studies have found that equal representation on the supervisory board (versus one-third representation) reduces the market-to-book ratio - a measure of firm performance - by 31% on average (Gorton and Schmid (2004). The authors conjecture that “labor succeeds in altering the objective function of the firm - away from maximizing shareholder wealth”, e.g. by resisting lay-offs and thus using their voting power as an insurance for employees in response to negative shocks. They also find evidence for high staffing levels and thus potential overstaffing in equal-representation firms.

On the other hand, employees might have a similar objective function as shareholders (or their representatives) aiming at the long-run survival of the firm, in which case employee representation could actually be beneficial for shareholders. One such overlap in employees’ and shareholders’ interest would be to prevent managers from pursuing overly risky projects, maximizing short-term profits, or engaging in expansion by mergers and acquisitions. The shareholders as members of the supervisory board can change the managers’ compensation structure to incentivize them to act according to their interest. Dyballa and Kraft (2016) find evidence that employee representation is beneficial in that regard.

Furthermore, there may be benefits due to an improved flow of information between board and workers. Due to their knowledge of a firm’s operations and processes, employees are good at monitoring managerial performance and bring first-hand knowledge to the board’s decision making (Edwards et al 2009, Fauver and Fuerst 2006). The latter find that codetermination can increase firm efficiency and market value. This finding is not necessarily incompatible with Gorton and Schmid (2004) as they do not stipulate that one-half representation is optimal but simply that a positive number of employee representatives is beneficial. The optimal level of labor representation might thus be below parity. They argue that their finding holds in particular for “industries that require more intense coordination, integration of activities, and information sharing such as trade, transportation, computers, pharmaceuticals, and other manufacturing”.

Information flows and work council presence

Beyond worker representation on boards, work councils as the other pillar of codetermination institutionalize cooperation between workers and employers. Workplace representation in Germany takes place mainly through work councils rather than unions (see Addison 2005 for a survey of the academic literature). These institutions aggregate information and preferences of workers and thus may help determine the social demand for public goods such as better working conditions. Work councils may also be beneficial in relation to workers’ input of effort, reducing exit behaviour (quits, absenteeism) and increasing firm-specific investments in human capital. Other benefits may be due to work councils’ information rights – by, e.g., verifying management claims and avoiding costly disputes -, consultation rights – leading to new solutions and creative discussion – and by encouraging workers to take a longer-run view of the firm by providing them more job security, a point also raised by Kommission Mitbestimmung (1998) further above. On the empirical side the findings are quite mixed, however. Most recent studies find neutral or small, positive effects on productivity, innovation, and investment. One study argues that the functioning of work councils also depends on its age, i.e. there is a learning effect (Jirjahn et al 2011). For example, the authors find that adversarial relationships between work councils and the management are decreasing, and productivity increasing, with its age.

Codetermination and equality

Finally, as the system of codetermination is also mentioned in the context of “democratic capitalism” and is meant to be an inclusive framework, it seems natural to wonder whether this also shows up in numbers. For obvious reasons, macroeconomic effects are hard to measure seriously. Nevertheless, Vitols (2005) looks at 25 EU countries and finds that countries with stronger worker participation rights perform better in terms of labor productivity, R&D intensity, and had lower strike rates, although this group of countries performed worse in terms of GDP growth. Hörisch (2012) looks at the association between codetermination and income inequality (measured using the Gini index) in OECD countries and finds that it is negative – i.e. higher income equality in countries with codetermination.

To conclude, there is plenty of evidence that the German stakeholder system of codetermination has been a positive experience, although there are also strong doubts about whether it is efficient or optimal. There are several other particularities of the German economic system – interaction between firms and other social partners, ownership structure of German firms etc – that are important to bear in mind when thinking about whether codetermination can also work elsewhere.

References

Dyballa, K. and K. Kraft (2016) ‘How do Labor Representatives Affect Incentive Orientation of Executive Compensation?’. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10153.

Edwards, J. S., Eggert, W., and A.J. Weichenrieder (2009) ‘Corporate Governance and Pay for Performance: Evidence from Germany’. Economics of Governance, 10(1), 1-26.

Fauver, L. and M.E. Fuerst (2006) ‘Does Good Corporate Governance Include Employee Representation? Evidence from Germand Corporate Boards’. Journal of Financial Economics, 82.3 (2006): 673-710.

FitzRoy, F. and K. Kraft (2004) ‘Co-determination, Efficiency, and Productivity’. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1442.

Freeman, R.B., and J.L. Medoff (1984) ‘What do unions do.’ Indus. & Lab. Rel. Rev. 38 (1984): 244.Gorton, G. and F.A. Schmid (2004) ‘Capital, labor and the firm: a study of German codetermination’. Journal of the European Economic Association Vol.2, No. 5

Hörisch, F. (2012) ‘The Macro-economic Effect of Codetermination on Income Equality’. MZES WP No. 147, 2012.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1979). Rights and production functions: An application to labor-managed firms and codetermination. Journal of Business, 469-506.

Jirjahn, U., Mohrenweiser, J., and U. Backes‐Gellner (2011) ‘Works councils and learning: On the dynamic dimension of codetermination’. Kyklos, 64(3), 427-447.

Kommission Mitbestimmung (1998) ‘Mitbestimmung und neue Unternehmenskulturen - Bilanz und Perspektiven‘. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh.

Lazear, E.P., and R. Freeman (1995).‘An economic Analysis of Works Councils’. In: Works Councils: Consultation, Representation, Cooperation. University of Chicago Press for NBER ; 1995. pp. 27-50.

Page, R. (2009) ‘Co-determination in Germany – A Beginner’s Guide’. Hans Böckler Stiftung, Arbeitspapier 33.

Vitols, S. (2005)‘Prospects for Trade Unions in the Evolving European System of Corporate Governance’.