The new Washington Consensus

What’s at stake: Since 2008 the IMF has been at the forefront of a revaluation of the orthodox policy toolbox. While the majority of policies that con

The Washington Consensus and neoliberalism

John Williamson coined the term Washington Consensus in 1989 as he examined the extent to which the old ideas of development economics that had governed Latin American economic policy since the 1950s were being swept aside by the set of ideas that had long been accepted as appropriate within the OECD.

John Williamson provided a list of ten policies that more or less everyone in Washington agreed were needed more or less everywhere in Latin America:

- Fiscal Discipline.

- Reordering Public Expenditure Priorities.

- Tax Reform.

- Liberalizing Interest Rates.

- A Competitive Exchange Rate.

- Trade Liberalization.

- Liberalization of Inward Foreign Direct Investment.

- Privatization

- Deregulation

- Property Rights.

Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri write that the neoliberal agenda rests on two main planks. The first is increased competition – achieved through deregulation and the opening up of domestic markets, including financial markets, to foreign competition. The second is a smaller role for the state, achieved through privatization and limits on the ability of governments to run fiscal deficits and accumulate debt.

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that contrary to some perceptions, the term neoliberal was not a US invention, but was first used by Rüstow. It was designed to be a ‘third way’ between socialism and a German version of capitalism. It was adopted by a group that later became the Mont Pèlerin Society, which included Mises and Hayek and Milton Friedman.

The decades of neoliberalism

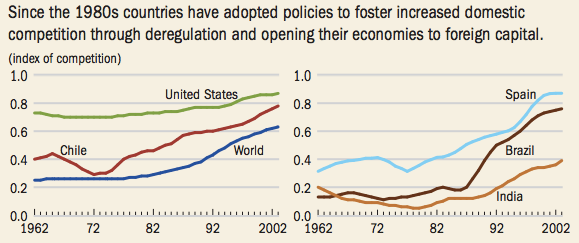

Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri write that there has been a strong and widespread global trend toward neoliberalism since the 1980s, according to a composite index that measures the extent to which countries introduced competition in various spheres of economic activity to foster economic growth.

Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri write that there is much to cheer in the neoliberal agenda. The expansion of global trade has rescued millions from abject poverty. Foreign direct investment has often been a way to transfer technology and know-how to developing economies. Privatization of state owned enterprises has in many instances led to more efficient provision of services and lowered the fiscal burden on governments.

Ricardo Hausmann writes that Venezuela’s current catastrophe is a reminder of what can happen when all orthodoxy is tossed out the window. One of those fundamentals is the idea that, to achieve social goals, it is better to use – rather than repress – the market. Suppose you do not like the outcome the market generates. A tradition, going back to Saint Thomas Aquinas, held that prices should be “just.” Economics has shown that this is a really bad idea, because prices are the information system that creates incentives for suppliers and customers to decide what and how much to make or buy. Making prices “just” nullifies this function, leaving the economy in perpetual shortage.

Ricardo Hausmann writes that another bit of conventional wisdom is that creating the right incentive structure and securing the necessary know-how to run state-owned enterprises is very difficult. So the state should have only a few firms in strategic sectors or in activities that are rife with market failures. Venezuela disregarded that wisdom and went on an expropriation binge. Productivity collapsed in all of them.

The new view

Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri write that the benefits of some policies that are an important part of the neoliberal agenda appear to have been somewhat overplayed. In the case of financial openness, some capital flows, such as foreign direct investment, do appear to confer the benefits claimed for them. But for others, particularly short-term capital flows, the benefits to growth are difficult to reap, whereas the risks, in terms of greater volatility and increased risk of crisis, loom large. In the case of fiscal consolidation, the short-run costs in terms of lower output and welfare and higher unemployment have been underplayed, and the desirability for countries with ample fiscal space of simply living with high debt and allowing debt ratios to decline organically through growth is underappreciated. Ricardo Hausmann writes that fiscal prudence is one of the most frequently attacked principles of economic orthodoxy. But Venezuela shows what happens when prudence is frowned upon and fiscal information is treated as a state secret.

Duncan Weldon writes that the Ostry and al. article is really just the latest in a series of moves from the Fund that can be seen as step away from the pre-2008 vintage “Washington Consensus”. All of which is a long way of saying the IMF — or at least the output of its research department — has moved along way. It is no longer the demon of left wing imaginations. On the other hand there is a very legitimate criticism that can be made that for all the progress made in the research department, the actual design of IMF programmes has