The procyclicality of TFP growth

What’s at stake: The argument that total factor productivity (TFP) is procyclical has been getting a lot of airtime over the past few weeks as it was

Alexander Field writes that between 1890 and 2004, TFP growth in the US was strongly procyclical. For over a century TFP growth varied systematically with the business cycle, and the elasticity of TFP growth with respect to a change in the unemployment rate was remarkably stable in the years before and after the Second World War and in a variety of subperiods during which trend growth rates of TFP were quite different. A fall in the unemployment rate by one percentage point led to an increase in the growth rate of TFP of about 0.9 percent per year. The three most serious twentieth-century output gaps developed in 1929-1933, 1974-1975, and 1979-1982. In each of these episodes, TFP declined sharply.

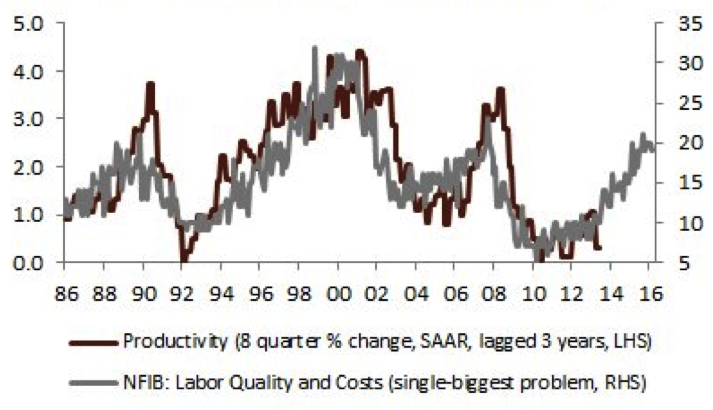

Source: Renaissance Macro via @M_C_Klein

Anti-hysterisis and the Sanders controversy

J.W. Mason writes that while there is increasing recognition in the mainstream of the importance of hysteresis, there’s little or no discussion of anti-hysteresis — the possibility that inflationary booms have long-term positive effects on aggregate supply. But I think it would be easy to defend the argument that a disproportionate share of innovation, new investment and labor force broadening happens in periods when demand is persistently pushing against potential. In either case, the conventional relationship between demand and supply is reversed — in a world where (anti-) hysteresis is important, “excessive” demand may lead to only temporarily higher inflation but permanently higher employment and output, and conversely.

Gerald Friedman writes that differences between my evaluation of the impact of the Sanders economic program from that of the Romers reflect the difference between a static model where national income and employment are largely fixed and a dynamic one where these are shaped by effective demand. If we agree that recessions induce a decline in productivity, why couldn’t a boom raise productivity growth through induced investment in equipment and facilities, and when employers seek to increase the efficiency of their operations to reap profits from expanding sales opportunities? This is a model consistent with some of the giants in the economics profession, including not only Keynes, Kaldor, and Verdoorn, and Schumpeter.

Evan Soltas writes that despite a cyclical relationship, it is not necessarily true that a policymaker could permanently raise productivity by keeping the output gap low. We see that productivity growth is correlated to the output gap. In fact, it is not only labor productivity but also total factor productivity that behaves in this way. Does that mean that running small output gaps would raise the long-run rate of productivity growth? Not necessarily. Here is a counterexample. Suppose that firms must split their workers between two activities, production and maintenance. It makes sense for firms to defer maintenance to times when more production is less beneficial to them on the margin, as in recessions. But no firm can defer maintenance forever.

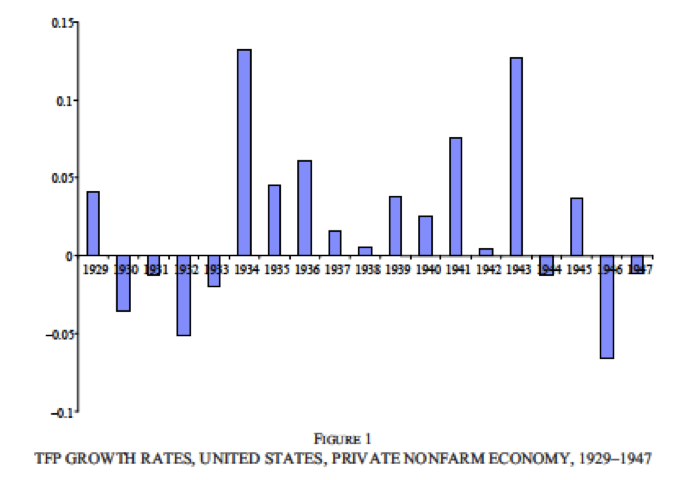

TFP growth in the Great Depression

Alexander Field writes that because of the Depression’s place in both the popular and academic imagination, it will seem startling to propose the following hypothesis: the years 1929–1941 were, in the aggregate, the most technologically progressive of any comparable period in U.S. economic history. Using more refined estimates of TFP growth, Gerben Bakker, Nicholas Crafts and Pieter Woltjer write that even though the 1930s saw the fastest TFP growth in the private domestic economy before WWII, it was not the most progressive decade of the whole 20th century as both 1948-60 and 1960-73 were superior at 2.0% and 2.2% per year, respectively.

Alexander Field writes that there is evidence that for some organizations and industries, just as for some individuals, adversity summons reservoirs of initiative and creativity that have long-term positive consequences. And based on Depression experience, we can be optimistic that when exciting technological paradigms are ripe for exploitation, work will continue on them, slump or no slump.

Gerben Bakker, Nicholas Crafts and Pieter Woltjer write that it seems reasonable to believe that rapid TFP growth in the 1930s was in spite of – rather than because of – the Great Depression. The resilience of TFP growth in the 1930s reflected US success in creating a strong ‘national innovation system’ based on world-leading investments in human capital and R&D and a market economy in which creative destruction could flourish, which had become well established by the first quarter of the 20th century.

Source: Alexander Field

Matthew D. Shapiro finds that much of the apparent cyclicality of total factor productivity is accounted for by variation in the workweek of capital. As expected, the workweek of capital is highly procyclical. In the trough year of 1982, capital's workweek is 5.3 hours below the industry-effects-adjusted mean while for the peak year of 1988 it is 5.2 hours above the mean.