Europe should not fear foreign takeovers

Foreign takeovers are often a source of concern for national governments. Concerns might be of a strategic nature (for example over deals in the defen

Foreign takeovers are often a source of concern for national governments. Concerns might be of a strategic nature (for example over deals in the defence sector) or of a more economic nature. In the latter cases, the public perception is often that, because they are less physically or psychologically attached to the host country, foreign investors could more easily take decisions that harm the host economy, such as downgrading the acquired company’s brand or cutting jobs or research expenditure.

There might be some substance to such concerns. In 2010 when United States food group Kraft purchased British chocolate maker Cadbury, the takeover was in part facilitated by an undertaking from Kraft that it would reverse a Cadbury decision to relocate some production from the United Kingdom to Poland. After the merger, however, Kraft went ahead with the plan to move production to Warsaw. Such events can make politicians wary of foreign takeovers. In the UK, similar concerns arose in spring 2014 when US company Pfizer attempted to buy Britain’s AstraZeneca. The UK government's concern was to avoid loss of R&D jobs following the deal. In this case, however, Pfizer ultimately dropped its offer and the merger did not take place. The government proposed to strengthen the ability of public authorities to impose conditions on buyers when mergers are attempted.

There are frequent calls for intervention by governments to protect the public interest when the takeover is attempted. But national governments are not supposed to play a role in the process.

Such debates occur everywhere in Europe. There are frequent calls for intervention by governments to protect the public interest when the takeover of a relevant national brand by a foreign investor is attempted. However, mergers of significant size that involve companies of different origins, be they European Union or non-EU companies, are normally subject to the European Commission’s scrutiny in its capacity of antitrust authority. National governments are not supposed to play a role in the process. This may create some inter-institutional tension since the guiding principle followed by the Commission during its merger assessments is to uphold the interests of the consumer only, while national governments might pursue other interests. No other criteria can affect the Commission’s decision. If, for example, a merger helps to rationalise production plants, reduces marginal costs of production and leads to lower market prices, this may be a sufficient condition for merger clearance. If the rationalisation of production plants also entails redundancies is not relevant to the Commission’s assessment. However, this does not mean that the Commission believes that these are negligible issues that should be ignored, but that other institutional instruments (such as redistribution and employment policies) are more appropriate to handle them rather than antitrust control.

In certain cases, namely when the merger affects public security, plurality of the media or prudential rules, national governments are allowed to intervene to protect these “legitimate interests” and impose conditions on mergers that fall in the jurisdiction of the European Commission (Art. 21 of the European Union Merger Regulation, EUMR). Other public interest concerns must be deemed ‘legitimate’ by the European Commission before governments can take action.

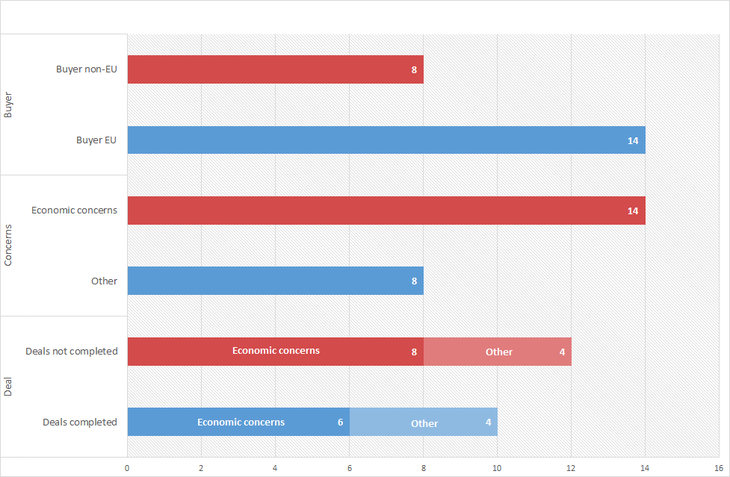

National governments’ concerns are often of a presumed economic nature. In a recent paper published by Bruegel, we look at 22 major acquisitions in which a foreign investor attempted to buy a domestic company in an EU country in the last 15 years, and the national government intervened in the process. In most cases (14 out of 22), concerns about the effects of an acquired company’s productivity, potential losses of jobs or reduction in R&D expenditure were key elements of the debate [see Figure 1 below]. In the majority of the cases in which economic concerns were expressed, the merger ultimately did not take place.

Number of major EU cross-border mergers in which buyer's nationality triggered government intervention (1999-2014)

Note: cases in the sample were identified through a review of the literature on foreign takeovers and merger control in Europe. Because sometimes those cases are not explicitly publicly reported, the list is not exhaustive. The sample includes the following cases: BSCH/A.Champalimaud, Secil/Holderbank/Cimpor, Thomson-CSF/Racal, Novartis/Aventis, ABN Amro/Banca Antonveneta, BBVA/BNL, Unicredito/HVB, Danone/PepsiCo, Enel/Suez, E.ON/Endesa, Abertis/Autostrade, Mittal/Arcelor, Gazprom/Centrica, MAN/Scania, Enel/Acciona/Endesa, AT&T/Telecom Italia, Air France-KLM/Alitalia, Kraft Foods/Cadbury, Lactalis/Parmalat, Edison/EdF, GE/Alstom, Pfizer/AstraZeneca. Economic concerns are identified if concerns about the effect of the merger on productivity, jobs or R&D by key players such as members of the government, the national parliament or trade unions were reported in the contemporary media

While a direct causal link between economic concerns and a deal’s outcome does not always exist (buyers might simply drop an offer because they do not reach an agreement on the price, for example), the public debate around the nationality of the buyer would normally significantly affect the process. This could take the form of additional delays, costs or specific commitments to be fulfilled by the parties, reducing the business appeal of a potentially valuable transaction. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that there is currently no clarity about the boundaries of government intervention. It is unclear what types of concerns could be considered ’legitimate public interests‘ by the Commission, and often governments succeed in influencing the process, even if the compatibility of their intervention with EUMR is questionable. For example, governments can successfully frustrate a deal by just threatening to interfere with the merger: companies might not be willing, to wait for the Commission to assess whether the action of the government is ’legitimate’ or to see if the Commission will challenge the member state’s (informal) interference before the European courts.

In the Bruegel paper we find that concerns of economic nature should not be considered legitimate reasons for government intervention. We examine the literature and find little backing for concerns related to the nationality of the acquiring company. It follows that EU member states should not be allowed any leeway to impose conditions to address economic concerns to the merging parties when a foreign takeover takes place, such as imposing an obligation to maintain a certain level of R&D expenditure in the host country. There is in fact a significant potential cost if that route is taken: any interference by a member state could affect normal market dynamics, distort competition and reduce the scope of the value that a transaction can bring. If the Commission correctly assesses a takeover, a foreign acquisition is likely to bring value to the European economy through increased competition, but that value might not be created if member states interfere to alter the outcome of the merger assessment process.

the Commission could publish detailed guidelines on how the public interest is defined and how national laws will be assessed.

To address these issues, reduce costs for foreign investors and minimise the risk of distortions in the process and of conflicts with national governments, the European Commission should clarify the institutional framework that defines the boundaries for government intervention, so that governments and companies can more easily anticipate the compatibility of any national intervention with EUMR. For example the Commission could publish detailed guidelines on how the public interest is defined and how national laws will be assessed.

Read More:

Policy Brief: Foreign takeovers need clarity from Europe