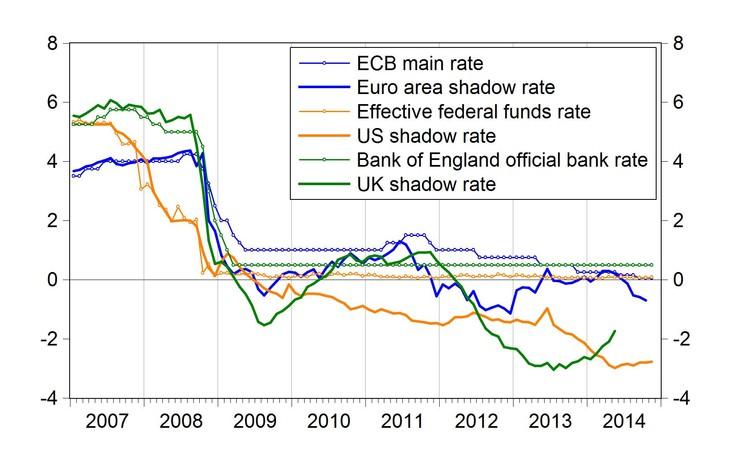

Central bank rates deep in shadow

Measuring the impact of monetary policy on the economy at the zero lower bound is difficult. After 2008, central banks cut policy rates close to zero

Measuring the impact of monetary policy on the economy at the zero lower bound is difficult. After 2008, central banks cut policy rates close to zero and implemented various unconventional measures, such as large-scale asset purchases in the United States, United Kingdom and Japan, or long-maturity lending to banks in the euro area. More recently, the European Central Bank cut deposit rates below zero and started the purchase of asset backed securities and covered bank bonds. Such unconventional measures are not reflected in key policy rates, which are stuck near zero.

At the zero lower bound other monetary indicators are needed. As I argued in a recent working paper, a properly measured indicator of money (the so-called Divisia-money) is one such indicator. Another indicator is a so-called estimated shadow interest rate. Such rates are estimated for the US, UK and euro area by Jing Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia, who utilised information from the term structure of interest rates in an unobserved components model. Their shadow rate estimates are virtually the same as the policy rates when policy rates were well above zero, but their shadow rate estimates turned negative for certain periods when the policy rates were very close to zero. Money and shadow rates are interlinked: in my working paper I found that a fall in the shadow rate increases Divisia-money growth and in turn an increase in Divisia-money growth increases GDP growth.

In a post seven months ago, Ashoka Mody plotted shadow rate estimates for the US and the euro-area and argued that the ECB must and can act. Since the ECB has announced a number of monetary policy measures since then, let’s look at more recent shadow rate developments.

Policy rates and estimated shadow rates (%)

Sources: Jing Cynthia Wu’s website for shadow rates, ECB, Bank of England and Federal Reserve Board for policy rates.

The figure suggests that the ECB achieved a much less accommodative monetary stance than the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. The recent measures (negative deposit rate, new long term refinancing operations and some asset purchases) pushed the estimated shadow rate below zero, yet it is still much higher than the approximately minus 3 percent shadow rates estimated for the US and UK for 2013-14, even though quantitative easing has ended there.

Since both the current inflation (0.3% in November 2014) and expected inflation (see Silvia Merler’s post on this) in the euro area is well below the inflation in the US and UK and well below 2%, there is indeed a strong case for the ECB to act. Ashoka Mody is right that the ECB is again well behind the curve.

A sizeable quantitative easing programme can have an impact in the euro area too, as we argued in a policy contribution I wrote with Grégory Claeys, Silvia Merler and Guntram B. Wolff in May this year. A good starter would be the purchase of European debt, which currently has an eligible pool of around €490 billion of EFSF, ESM, EU and EIB bonds.