Obama’s executive action on immigration

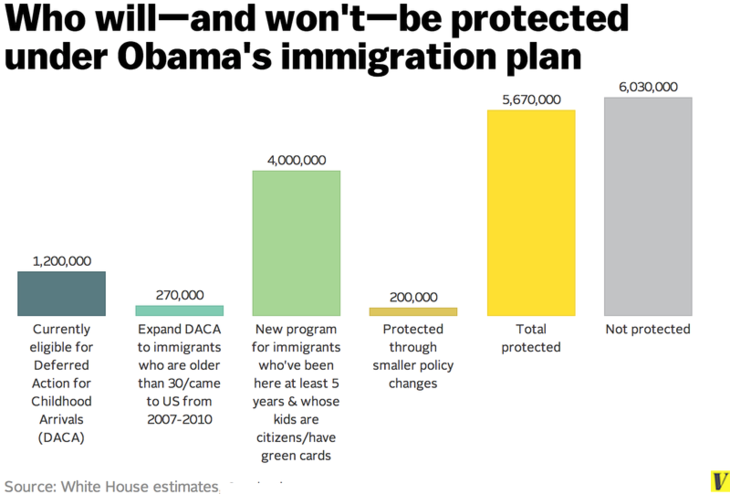

What’s at stake: The President of the United-States announced sweeping changes to the immigration system via executive action this week to protec

The action on un-authorized immigration

The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers explains that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) will:

- Expand the existing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) which allows young people who came to the country before turning 16 years old who meet certain education guidelines, such as graduating from high school or attending college, to request temporary relief from removal (“deferred action”) and be eligible to obtain work authorization.

- Establish a similar process for parents of U.S. citizens or Lawful Permanent Residents (LPRs) who have been in the country for five years or more to request deferred action.

Dara Lind writes that the president doesn't have the authority to give anyone legal status in the US. But the current system gives the executive branch broad authority to decide what it wants to prioritize when it comes to immigration enforcement. It’s therefore incorrect to describe the centerpiece of President Obama's executive actions on immigration as a "legalization" program. Although it offers protection from deportation, it does not change those immigrants' legal status (or rather, lack of legal status). Because deferred action doesn't give legal status, the President can reverse it at any time.

The action on authorized immigration

The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers points that the President’s announcements also included:

- Expanding immigration options for foreign entrepreneurs who have created American jobs or attracted significant investments.

- Extending on‐the‐job training for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduates of U.S. universities through reforms to the existing Optional Practical Training (OPT) program.

- Providing work authorization to spouses of individuals with H‐1B status who are on the path to LPR status.

- Providing portable work authorization for high‐skilled workers awaiting processing of LPR applications.

Foreign entrepreneurs and the “significant public benefit” parole authority

Matthew Yglesias writes that the most aggressive move the Administration is making concerns something foreign technology entrepreneurs. A memo released today by the Department of Homeland Security clarifies that Obama is planning to increase the number of foreign entrepreneurs allowed in. A memo from the Council on Economics Advisors suggests the scale of this program will involve around 33,000-53,000 new migrants. The legal basis for this action involves a break with precedent that is much more dramatic than the more-controversial deportation protection being given to unauthorized immigrants who are already here.

The memo from the Department of Homeland Security writes that the resulting backlogs for green cards prevent U.S. employers from attracting and retaining highly skilled workers critical to their businesses. U.S. businesses have historically relied on temporary visas – such as H-1B, L-1B, or O-1 – visas-to retain individuals with needed skills as they work their way through these backlogs. But as the backlogs for green cards grow longer, it is increasingly the case that temporary visas fail to fill the gap. Pursuant to the “significant public benefit” parole authority, USCIS should propose a program that will permit DHS to grant parole status, on a case-by-case basis, to inventors, researchers, and founders of start-up enterprises, who have been awarded substantial U.S> investor financing or otherwise hold the promise of innovation and job creation through the development of new technologies or the pursuit of cutting-edge research.

Macro economic effects

Cardiff Garcia writes that changes to immigration policies, or to any policies that target the labor market, can influence economic growth through some combination of three effects: by expanding the potential size of the US labor force (from more immigration), by increasing the labor force participation rate (from making it easier for immigrants to work), and by raising productivity growth (from greater specialization, partly depending on the skill level of the immigrants). Obama’s order would likely raise economic growth through the last two effects, while the first effect would be negligible.

Matt O’Brien writes that while they're working, these undocumented workers are not working in the jobs that would make the best use of their talents. In other words, they're stuck in unproductive jobs, because they don't have the papers to apply for better ones. Adam Ozimek send us to a 2002 paper from Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark found that following the 1986 illegal immigrant amnesty, the wages of those amnestied rose 6% between 1989 and 1992. They found that the majority of the wage penalty of being illegal is due to an inability to move between occupations.

Immigration and inequality

Owen Zidar writes that there are a few reasons why labor demand may also shift out following an increase in immigration: 1/ Immigrants consume goods and services and increase demand (and thus labor demand) for those products. 2/ Common production functions predict a constant capital to labor ratio, which predicts that higher L will eventually mean more investment and thus more labor demand. 3/ Immigrants could help increase productivity.

The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers writes that theory suggests that these policy changes would not have an effect on the long‐run employment (or unemployment) rate of native workers as the additional demand associated with the expanded economy would offset the additional supply of workers. Consistent with the theory, much of the academic literature suggests that changes in immigration policy have no effect on the likelihood of employment for native workers. Although we hypothesize that administrative action will have no long‐run effect on the quantity of jobs held by native workers, our analysis of changes in output per worker implies that these actions will increase the quality of native‐worker jobs and thus these workers’ wages.

Cardiff Garcia writes that it should be known that the CEA report does cherry pick from within the existing literature on immigration economics. For instance there are thirty-three mentions of Giovanni Peri, all of them favorable. Peri is the pro-immigration economist’s pro-immigration economist. The report only mentions George Borjas, who is well known for his skepticism about the employment and wage effects of immigration, three times — and does so to contradict his findings.