The forever recession

As the recovery takes hold in the US, Europe appears stuck in a never-ending slump. With the ECB systematically undershooting its inflation targe

What’s at stake: As the recovery takes hold in the US, Europe appears stuck in a never-ending slump. With the ECB systematically undershooting its inflation target and recent signs that inflation expectations could become de-anchored, the bulk of commentators in the blogosphere are again calling for more monetary actions. Noticeably, some have completely lost hope in the ability of the European institutions to turn this situation around and are now calling for countries to simply break away from the EMU trap.

The greater depression

The Economist writes that this week’s figures for the euro-zone economy were dispiriting by any measure. An already feeble and faltering recovery has stumbled. Output across the euro area was flat in the second quarter. The new GDP figures are yet more evidence that the euro-zone economy is in a bad way. It is not only that growth is evaporating; inflation is also extraordinarily low.

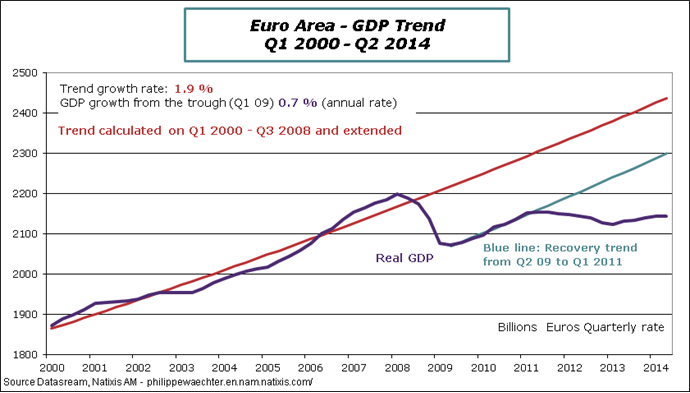

After six-and-a-half years eurozone GDP is still 1.9 percent lower than it was before the Great Recession

Matt O’Brien writes that it's been six-and-a-half years, and eurozone GDP is still 1.9 percent lower than it was before the Great Recession began. It "only" took the U.S. economy seven years to get back to where it'd been before the Great Depression hit. Eurointelligence writes that until earlier this year, the eurozone’s macroeconomic development was a core vs. periphery story. If that had continued, the eurozone would have gone through a somewhat painful adjustment. But with core economies growth and inflation also low and falling, this is not happening. Brad DeLong writes that in the middle of 2011 it was possible to say that Germany had recovered from the crisis, that the remaining problems of southern Europe were the result of their own fecklessness, and that German growth was about to resume–it was wrong to say that, but it was possible. But we will soon have three years of no industrial production growth in Germany.

It takes spectacular policy errors to bring about such an outcome in a modern economy

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard writes that it takes spectacular policy errors to bring about such an outcome in a modern economy. Eurointelligence writes that this is a recession caused by policy failure. It was not a financial crisis that has damaged the eurozone as much as the policy response to it: obsessive deficit cutting in a poisonous conjunction with obsessive central bankers (who obsess about everything, except meeting their own inflation target).

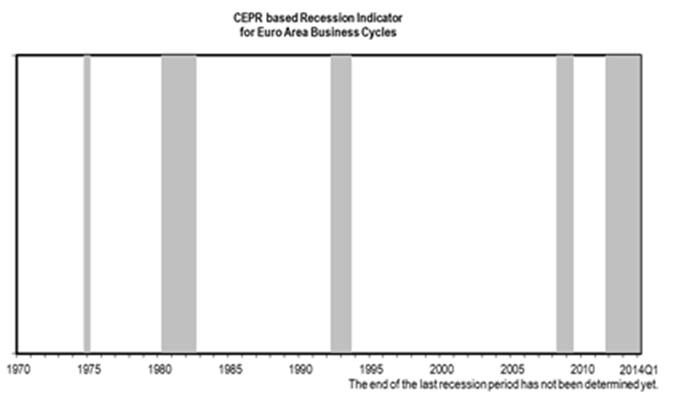

Jeffrey Frankel writes that the peculiar way individual European economies define a recession makes it harder for the public to see that the same wrong policies have been followed throughout the crisis. Under U.S. standards (where the start and the end of a recession is determined by a cycle dating committee) Italy would, for example, probably be treated as having been in the same horrific six-year recession ever since the shock of the global financial crisis in 2008. Citizens in Italy have now been given the impression that they have entered a new recession. Voters may draw the conclusion that their new political leaders must have done something wrong. But the picture is different if Italy has been in the same recession for six years. The implication may be that the leaders have been doing the same wrong things throughout that period.

Structural reforms, the ECB and the EMU trap

Antonio Fatas writes the central bank should, as in the US, communicate its view on how close the economy is to potential output, how much slack there is in the economy and how they plan to use their economic tools to address that gap. Otherwise, by always invoking structural reforms, the ECB sounds defensive as if they feel too much pressure to lift growth rates and they want to explain to the public at large that the low economic performance is not really their fault but the fault of governments' failure to reform.

Wolfgang Munchau writes that if the ECB continues blaming eurozone governments for not implementing structural reforms and continues missing its own targets, the eurozone will end up looking like Japan, but with one difference. Countries whose policy goes off track have nowhere to go. The member states of a monetary union have alternatives. By failing to deliver on its inflation target, the ECB could give member countries a good reason to leave the eurozone: they could have a better central bank.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard writes that there is no point negotiating. The European institutions have failed to ensure a symmetric adjustment that compels both North and South to take equal steps to close the intra-EMU divide from both ends, befitting their equal responsibility for mismanaging the EMU joint venture in its early years. Italy must look after itself. It can recover only if it breaks free from the EMU trap, retakes control of its sovereign policy instruments and redominates its debts into lira, with capital controls until the dust settles.

The euro is the gold standard with moral authority

Matt O’Brien writes that the euro is the gold standard with moral authority. And that last part is a problem. Both are fixed exchange rate systems that can turn a recession into a depression, because they make countercyclical policy impossible. But people are even more attached to the euro today than they were to the gold standard then. Now, in the 1930s, people equated the gold standard with civilization itself, and were willing to sacrifice their economies for it. The euro doesn't just represent civilization, but the defense of it, too. After all, the past 60 years of civilization have all been about making sure it never happens again. Europe's leaders aren't going to give that up because of a little thing like a never-ending slum.