The Fed and the Secular Stagnation hypothesis

Experts have debated whether we should worry about systemic saving-investment mismatches and what to do about them. But the extent to which monetary p

What’s at stake: Larry Summers made a big splash in late 2013 when he re-introduced the secular stagnation hypothesis to explain the disappointing recovery from the Great Recession. Experts have since debated whether we should worry about systemic saving-investment mismatches and what to do about them. But the extent to which monetary policymakers have already revised their views about the long-run equilibrium interest rate has remained quite unnoticed so far.

The new secular stagnation hypothesis

Barry Eichengreen writes that the idea that America and the other advanced economies might be suffering from more than the hangover from a financial crisis resonated with many observers. Coen Teulings and Richard Baldwin write that this ill-defined sense that something had changed was given a name when Larry Summers re-introduced the term ‘secular stagnation’ in late 2013.

Secular stagnation usually refers to a situation in which saving can only equal investment at a negative real interest rate

Juan F. Jimeno, Frank Smets and Jonathan Yiangou write that secular stagnation usually refers to a situation in which saving can only equal investment at a negative real interest rate – an equilibrium that cannot be achieved because of the zero lower bound (ZLB) constraint on interest rates and low inflation. Laurence Summers writes that the ‘new secular stagnation hypothesis’ responds to recent experience and the manifest inadequacy of conventional formulations by raising the possibility that it may be impossible for an economy to achieve full employment, satisfactory growth, and financial stability simultaneously simply through the operation of conventional monetary policy.

Secular stagnation and the pace of policy normalization

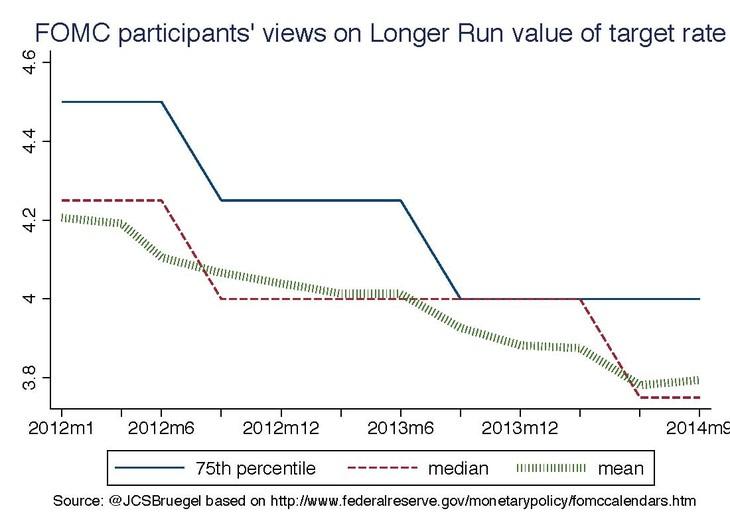

David Beckworth writes that the FOMC projections that are available show a pronounced downward trend in the "longer run" forecast of the federal funds rate. Alex Rosenberg writes that when it comes to what the markets ultimately care about in the short term—Fed policy—there's one thing nearly everyone can agree on: fresh concerns about secular stagnation are likely to make the Fed even more nervous about reducing accommodation too soon.

During the latest FOMC press conference, Steven Beckner pointed out that the Summary of Economic Projections assessments of appropriate funds rate levels show the funds rate getting up to that 3.75 percent normal level at the end of 2017. If you look at the SEP projections of unemployment, inflation, and so forth, they seem to get back to those mandate-consistent levels by the end of 2016, if not much sooner. So what is the justification for waiting that much longer to get back to normal?

In her response, Janet Yellen said that the story is […] not that the Fed is behind the curve in failing to return the funds rate to normal levels when the economy is recovered. It is rather that, in order to achieve such a recovery in 2016 or by the end, that it’s necessary and appropriate to have a somewhat more accommodative policy than would be normal in the absence of [several] headwinds. [A] common view on this is that there have been a variety of headwinds resulting from the crisis that have slowed growth, led to a sluggish recovery from the crisis, and that these headwinds will dissipate only slowly.

How to model secular stagnation?

Paul Krugman writes that if you look at the extensive theoretical literature on the zero lower bound since Japan became a source of concern in the 1990s, you find that just about all of it treats liquidity trap conditions as the result of a temporary shock.

Something – most obviously, a burst bubble or deleveraging after a credit boom – leads to a period of very low demand, so low that even zero interest rates aren’t enough to restore full employment

Something – most obviously, a burst bubble or deleveraging after a credit boom – leads to a period of very low demand, so low that even zero interest rates aren’t enough to restore full employment. Eventually, however, the shock will end. The idea that the liquidity trap is temporary has shaped the analysis of both monetary and fiscal policy.

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that a basic idea behind secular stagnation is that the natural real rate of interest might become negative for a prolonged period of time. A simple way to model this would be to allow the steady state real interest rate to become negative. But that cannot happen in basic representative agent models since the steady state real interest rate is pinned down by the discount factor of the representative agent.

Gauti Eggertsson and Neil Mehrotra write that in representative agent models the natural rate of interest can only temporarily deviate from this fixed state of affairs due to preference shocks or some similar alternatives. Changing the discount rate permanently (or assuming a permanent preference shock) is of no help, since this leads the intertemporal budget constraint of the representative household to ‘blow up’ and the maximization problem of the household to no longer be well defined. Moving away from a representative savers framework to one in which households transition from borrowing to saving over their lifecycle can, however, open up the possibility of secular stagnation. The key here is that households shift from borrowing to saving over their lifecycle. If a borrower takes on less debt today (due to the deleveraging shock), then tomorrow he has greater savings capacity since he has less debt to repay. This implies that deleveraging will reduce the real rate even further by increasing the supply of savings in the future.

Read more on secular stagnation

Monetary policy cannot solve secular stagnation alone

Secular stagnation in today's economy. How can it be addressed?