Ukraine: Can meaningful reform come out of conflict?

Ukraine urgently needs a complex programme of far-reaching economic and institutional reform, which will include both short-term fiscal and macroecono

- Apart from threats to its national security and territorial integrity, Ukraine faces serious economic challenges. These result from the slow pace of economic and institutional reform in the previous two decades, the populist policies of the Yanukovych era and the consequences of the conflict with Russia.

- The new Ukrainian authorities have made pro-reform declarations, but these do not seem to be supported sufficiently by concrete policy measures, especially in the critical areas of fiscal, balance-of-payment and structural adjustment. Also, the international financial aid package granted to Ukraine has not been accompanied by sufficiently strong policy conditionality.

- Ukraine urgently needs a complex programme of far-reaching economic and institutional reform, which will include both short-term fiscal and macroeconomic adjustment measures and medium- to long-term structural and institutional changes.

- Energy subsidies and the low retirement age are the two critical policy areas that require adjustment to avoid sovereign default and a balance-of-payments crisis.

Introduction

Since the end of 2013 Ukraine has faced a series of dramatic geopolitical, domestic political and economic challenges. First, there was mass protest in Kyiv’s central square against former president Viktor Yanukovych after he declined to sign an association agreement with the European Union. After collapse of Yanukovych’s regime, the internal Ukrainian conflict became internationalised with the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia, and Russia’s active role in a ‘proxy’ war in the Donetsk and Lukhansk regions.

For this reason, international attention is concentrated on geopolitical threats and the violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. The geopolitical and security challenges are also at the top of the agenda for the new president and government of Ukraine. As result, the economic situation and economic reform are less prioritised, domestically and internationally. However, pressing economic questions must also be addressed. The unsatisfactory results of previous reform rounds were very much responsible for the recent political crisis and the fragility of the Ukrainian state. Most importantly, successful economic and institutional reforms are critical for attempts to consolidate both state and society and to prevent any new authoritarian drift.

The new Ukrainian authorities have made general pro-reform declarations, but these do not seem to be supported sufficiently by concrete policy measures, especially in the critical areas of fiscal, balance-of-payment and structural adjustment. The same must be said about the international financial aid package granted to Ukraine in April and May 2014, which has not been accompanied by sufficiently strong policy conditionality.

History of half-hearted reform

The recent developments in Ukraine are not the first time since independence in 1991 that the country has found itself at a critical juncture. In 1991-92, under Leonid Kravchuk’s presidency and on a wave of independence enthusiasm, Ukraine had the chance to build new democratic and market institutions as was done, for example, by the Baltic countries. Unfortunately, all the political energy went to giving old Soviet institutions ‘new’ Ukrainian names. The macroeconomic and social populism of that period led to hyperinflation at the end of 1993.

After Leonid Kuchma’s victory in the 1994 presidential election, some market reforms were finally enacted: most prices were liberalised, the exchange rate system was unified, subsidies and the fiscal deficit were reduced (but not eliminated), the issuing of money was brought under control and, finally, a new currency, the hryvna (UAH), was introduced in September 1996. This half-hearted reform process was stalled by a coalition of emerging oligarchs – the early winners from partial liberalisation and the macroeconomic disequilibria of early the 1990s, and the beneficiaries of various rents created by them – and old-style ‘red’ directors in industry and agriculture.

The next reform push came after the financial crisis of 1998-99 and Kuchma’s re-election in 1999 alongside Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko, the former governor of the National Bank of Ukraine. There was some fiscal adjustment, reform of the management of public finance and attempts were made to restructure the loss-making and heavily corrupted energy sector. However, the political life of Yushchenko’s government was short (17 months) and it was soon replaced by a government that was again dominated by ‘red’ industrialists and oligarchs.

After the Orange Revolution at the end of 2004 and Yushchenko’s election as the third president of Ukraine, there was a political window of opportunity to start serious political, institutional and economic reform. Unfortunately, this was prevented by a political split inside the ‘Orange’ camp, in particular, the permanent political infighting between Yushchenko and twice Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko (2005 and 2007-10). The only success of the period were entering the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2008 and starting negotiations with the EU on the association agreement.

The economic boom of 2000-07 did not create pressure for serious reform either. The macroeconomic situation improved: after 10 years (1990-99) of steep output decline and thanks to reforms that were partially completed at the beginning of the new millennium (especially privatisation of the larger part of the manufacturing industry), a rapid recovery started. This was also fuelled by the 2003-07 global boom (high prices of metals and agriculture commodities, Ukraine’s main exports) and an oil boom in Russia. The UAH exchange rate stabilised against the dollar, inflation diminished for a while, and the fiscal deficit and public debt to GDP ratio declined as result of rapid GDP growth. On the institutional front, the economic system could be considered largely a market system, but heavily distorted by pervasive corruption and nepotism, poor governance (which made implementation of market-related legislation and definition of the rules of the game a permanent problem) and state capture by oligarchic groups, similar to most other post-Soviet countries.

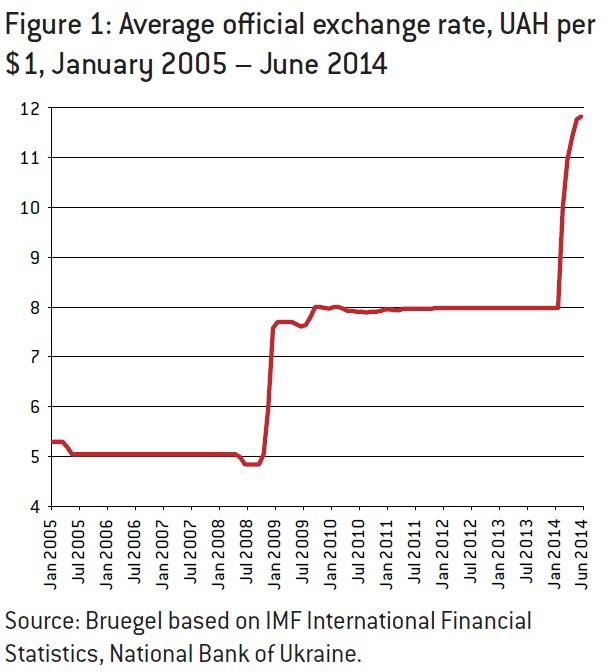

The era of relative prosperity came to the abrupt end with the global financial crisis in 2008. The era of relative prosperity came to the abrupt end with the global financial crisis in 2008. Ukraine was particularly heavily hit, recording in 2009 a decline in GDP of 14.8 percent (Table 1), one of the steepest falls of all emerging-market economies. Despite a low public-debt-to-GDP level (12.3 percent of GDP in 2007), Ukraine was cut off from international markets because of a current account deficit (-7.1 percent of GDP in 2008), external debt exceeding 50 percent of gross national income, external debt service costs equal to 20 percent of export proceeds, and expectations of devaluation. Between September 2008 and January 2009, the UAH depreciated by almost 60 percent, from 4.85 to 7.70 UAH to the dollar, and then further down to 8 UAH to the dollar in 2009 (see Figure 1). Ukrainian authorities had to ask for the International Monetary Fund Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) in the second half of 2008.

Legacy of the Yanukovych era

After the victory of Viktor Yanukovych (who had been prime minister in 2002-04 and 2006-07) in the February 2010 presidential election, and the formation of the government of Mykola Azarov, a new reform effort was declared. Legislation was adopted related, among other issues, to social policy (a gradual increase in the retirement age of women from 55 to 60, lengthening the service period needed to obtain a minimum pension and, for various privileged groups, limiting the maxi-mum pension to 10 times the subsistence mini-mum), Ukraine’s WTO membership commitments, and preparing the legal ground for the forthcoming EU-Ukraine association agreement (including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement, DCFTA). However, corruption and predatory pressure from the narrow oligarchic elite around the president and his family led to a deterioration in the already poor business climate and further declining confidence in state institutions. The continuously deteriorating total investment rate, and the declining gross national savings rate (see Table 1) illustrate well the macroeconomic consequences of dysfunctional governance.

Governance failings and authoritarian drift created fertile social ground for the wave of civil unrest that erupted as the Euro-Maidan protest movement in November 2013, after it became clear that the government would not sign the association agreement with the EU (see the next section).

Another source of social disappointment was the deteriorating economic situation. After the 2008-09 crisis, Ukraine failed to return to its pre-crisis GDP level (Table 1). In 2010 and 2011, GDP grew by 4.1 and 5.2 percent, respectively (not enough to compensate for the 2009 output decline), followed by stagnation in 2012-13. Stagnation was a result of weak external demand (a consequence of the European debt and financial crisis), increasing domestic imbalances, a deteriorating business and investment climate and increasing Russian import restrictions – Russia wanted to discourage the government of Ukraine from signing the association agreement with the EU.

The Azarov government’s populist policies, such as keeping domestic energy prices low and generous wage1 and pension increases, led to deteriorating fiscal and current account balances, a typical manifestation of the twin deficits. These policies also effectively derailed the two subsequent IMF SBAs (of 2008 and 2010), both backed by the EU’s Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA). As result, from summer 2013, Ukraine started to face the growing danger of the subsequent balance-of-payments crisis (the two previous balance-of-payments crises happened in 1998-99 and 2008-09).

Relations with the EU

In 1990s and early 2000s, the EU’s relationships with countries of the former Soviet Union other than the Baltic states were based on the bilateral Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCA) which included, in the economic sphere, the Most-Favoured Nation clause, and technical, legal and institutional cooperation in such sectors as transportation, energy, competition policy, and some legal approximation in the areas such as customs law, corporate law, banking law, intellectual property rights, technical standards and certification. Ukraine signed the PCA in June 1994 and the agreement entered into force on 1 March 1998.

The next steps, after the start of the European Neighbourhood Policy in May 2004 and the Orange Revolution in Ukraine at the end of 2004, were the signing the of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan and the granting of market economy status to Ukraine (both in 2005). The action plan was updated and upgraded into the EU-Ukraine Association Agenda3 in 2009 and then, once again, updated in June 2013 with the focus on implementation of the forthcoming association agreement4.

In March 2007, the EU and Ukraine started negotiations on a new enhanced agreement to replace the PCA. At the Paris EU-Ukraine Summit in September 2008, the negotiated agreement was upgraded to the association agreement and included the DCFTA as an integral part. The negotiation was concluded in December 2011, and the text of the association agreement was initialled on 30 March 2012 and signed on 27 June 2014 after a series of dramatic political events in 2013 and first half of 2014. These included the failure of Yanukovych’s administration to meet the political preconditions for signing the association agreement stipulated by the EU (related to fair elections, judicial reform and so-called selective justice against opposition leaders5), the subsequent last-minute refusal to sign the association agreement during the Third Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius on 28-29 November 2013, the resulting Euro-Maidan mass protests in Kyiv and regime change (November 2013 – February 2014), Russian annexation of Crimea and war in eastern Ukraine (since March 2014).

The association agreement, in particular, its DCFTA component, will offer Ukrainian companies partial access to the European single market. At the same time, it might stimulate regulatory and institutional reforms in trade and investment-related spheres, and ease the business climate for domestic and foreign firms. It can also help to bring the country’s legal system, public administration and infrastructure services closer to EU standards (the acquis), depending on the political will and determination to reform on the Ukrainian side.

Economic challenges posed by the current crisis

The combination of recent dramatic political developments and the deteriorating economic situation has made the current crisis particularly serious and severe. Ukraine faces an existential threat to its independence and territorial integrity caused by Russia’s aggressive policy, and must also overcome the adverse consequences of its past failures in economic and institutional reform to secure its survival and rebuild domestic and international confidence.

As result of the violent conflict in eastern Ukraine and the related political uncertainty, real GDP will decline in 2014. According to the IMF estimate built into the SBA assumptions, the decline could reach 5 percent; according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development May 2014 forecast it could even reach 7 percent.

Decline in GDP and political turmoil, including war in the east, have undermined seriously the revenue flow to Ukraine’s budget and have created additional expenditure needs, especially in the area of national defence and security, humanitarian assistance and infrastructure repair. The same IMF estimates of April 2014 predicted an increase in the general government deficit to 5.2 percent of GDP in 2014 from 4.8 percent in 2013, despite the recommended fiscal adjustment. If the quasifiscal deficit of Naftogaz (the state-owned monopoly in charge of natural gas imports and distribution) is added, the combined deficit will increase from 6.7 percent of GDP in 2013 to 8.5 percent of GDP in 2014. Generally, the IMF projections are based on optimistic assumptions. They might underestimate the downside risks in the national security sphere, potential further disruption to trade relations with Russia and bank recapitalisation needs.

In the first half of 2014, the hryvna depreciated from 8 UAH to more than 11.5 UAH to the dollar, i.e. more than 45 percent. In the face of a looming balance-of-payments crisis, such an adjustment was both unavoidable and necessary to improve trade and current account balances. However, it has also put an additional burden on the balance sheets of unhedged banks, companies (including Naftogaz) and households. The ratio of non-performing loans (NPL) to total loans in the banking sector amounted to 23.5 percent at the end of 2013, i.e. before the UAH depreciation.

Overcoming these negative tendencies requires not only political stabilisation but also far-reaching fiscal adjustment and structural and institutional reforms to help eliminate macroeconomic disequilibria and unlock Ukraine’s long-term growth potential, as we detail in the next section.

International aid package

The international community supported the new Ukrainian authorities with a generous financial aid package. At the core of this package is the 24-month $17.1 billion IMF SBA, i.e. 800 percent of Ukraine’s quota in the Fund6, provided under so-called exceptional access7. The first tranche, which was disbursed immediately after the SBA’s approval (on 30 April 2014), amounted to about $3.2 billion, of which $2 billion could be used as budget deficit financing.

In April 2014, the IMF SBA was backed by an EU MFA loan of €1 billion available in two instalments and the EU’s grant of €355 million (also in two instalments) under the State Building Contract.

Recently, the World Bank approved two loans to Ukraine – the District Heating Energy Efficiency Project of $382 million and the Social Safety Nets Modernisation Project of $300 million. The US Government provided loan guarantees amounting to $1 billion. Investment loans can be provided by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank.

Weak conditionality

Even the most generous international aid package can provide only temporary respite to Ukraine’s balance of payments. To ensure the sustaining effect, aid must be supplemented by a domestic adjustment and reform package which aims at removing the roots of domestic and external imbalances. This is why the conditionality attached to financial aid should require reform of policies and institutions. However, such conditions are not obvious in the content of the IMF SBA and EU assistance.

The IMF SBA said the following reforms should be implemented:

- Changes to the monetary policy regime, i.e. replacing the de-facto fixed but adjustable peg of the UAH to the dollar by a flexible exchange rate and inflation targeting, with the targeting of monetary aggregates as the intermediate solution in 2014;

- Financial sector stability, i.e. in-depth diagnosis of Ukrainian banks and their recapitalisation needs (if necessary), and bringing banking regulations into line with best international practices;

- Gradual reduction of the structural fiscal deficit;

- Modernisation and restructuring of the energy sector, gradual adjustment of end-user energy prices accompanied by development of the respective social safety net;

- Structural and governance reforms, improving the business climate.

At first glance, this looks like a comprehensive approach that aims to address key challenges faced by the economy of Ukraine. However, detailed proposals raise some doubts.

In fact, structural and governance reforms which are essential for improving the business climate and investors’ confidence have not been detailed in the SBA at all. There are no structural bench-marks – they are to be the subject of a separate diagnostic study.

The memoranda signed between the Government of Ukraine and the European Commission on the occasion of both the MFA and the State Building Contract are a bit more concrete in this respect. They set out some detailed conditions on fighting corruption, avoiding conflicts of interest for public servants, government transparency, changes in public procurement legislation and practices, public access to information, civil service reform, constitutional reform, election law and financing for political parties. However, very important areas such as deregulation of business activity, simplifying public administration structures and procedures, reform of the judiciary and law enforcement agencies and decentralisation (building genuine local and regional self-government) are virtually absent.

As we have noted, exchange-rate adjustment was crucial in avoiding a full-scale and uncontrolled currency crisis earlier this year. Similarly, attempts to make the exchange rate more flexible, together with the abandoning of existing restrictions on current account convertibility, should be welcomed. However, moving to inflation targeting in a one-year period does not look feasible, especially in a time of political and security turmoil and continuous fiscal pressure on monetary policy, and considering the limited legal and actual independence of the National Bank of Ukraine.

In order to create room for more independent monetary policy and an inflation-targeting regime, serious fiscal adjustment is needed, but on this the IMF programme looks rather weak and unconvincing. The fiscal adjustment target of 2 percent-age points of GDP annually plus another 1 percentage point of GDP of quasi-fiscal adjustment by Naftogaz cannot prevent further rapid increases in Ukraine’s fiscal deficit and public debt. According to the SBA targets, the general government deficit will stay at the level of 4.2 per-cent of GDP (without Naftogaz) and 6.1 percent of GDP (including Naftogaz) in 2015. Furthermore, several risks have been evidently underestimated in this projection, as we have noted.

As result of lax fiscal policy, the public debt-to-GDP ratio will jump from 40.9 percent in 2013 to 56.5 percent in 2014 and further up to 62.1 percent in 2015. Then it will reduce slowly to 51.9 percent in 2018, under the assumption that the economy will grow by at least 4 percent annually from 2016. So far, the government of Ukraine faced problems accessing private financial markets even at a much lower level of public debt. Similar public-debt funding constraints have been experienced by other post-Soviet and developing countries with similar characteristics to Ukraine. In practical terms, this means that despite the IMF programme, Ukraine will remain cut off from private debt markets for several years, and will be totally dependent on official financial aid.

Furthermore, without bolder fiscal adjustment there is no chance to increase substantially the very low rate of gross national savings (6 percent of GDP in 2013), because most private savings are absorbed by the public sector borrowing requirements, or to improve the current account balance. In turn, this will mean continuous balance-of-payments vulnerability and a limited pool of resources to finance investment.

Some of the proposed fiscal adjustment measures go in the right direction, such as abandoning the previous populist decision to replace the 20 per-cent VAT rate with two much lower rates. However, the fiscal effects of some one-off steps, for example, fighting tax fraud, might be overestimated. Wage and hiring freezes in the public sector might complicate the badly-needed reform of the civil service and public services such as education and healthcare. The Ukrainian public sector suffers from an excessive number of employees, who are poorly paid and managed. In such a situation, targeting the public-sector wage bill would be a better strategy to create both financial room and incentives for deep restructuring of both public administration and major public-service sectors.

In two areas of fiscal adjustment, the SBA looks particularly disappointing: elimination of energy subsidies and social welfare reform.

Energy subsidies

According to the IMF estimate8 post-tax energy subsidies in Ukraine amounted to 7.6 percent of GDP in 2012. They are much higher than in other countries of central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, apart from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Most subsidies have the quasi-fiscal form (periodical recapitalisation of Naftogaz) and are aimed to support low house-hold tariffs for natural gas and district-heating services (which use natural gas as an input). The price paid by Ukrainian households for natural gas covers only about 20 percent of the cost-recovery level, and is ten times or more lower than the price paid by Lithuanian and Estonian households.

Low domestic energy prices are not only responsible for high fiscal and quasi-fiscal deficits and the deteriorating current account balance. They do not help to reduce excessive energy consumption and increase energy efficiency, which in Ukraine is among the lowest in the world and has hardly improved since 1990 (Table 2).

Furthermore, low energy prices do not create incentives to increase domestic energy production and invest in energy-saving technologies. They do not allow the elimination of one of the most obvious sources of corruption – trading in, and distribution of, subsidised energy imports – and they prevent the reorientation of the energy sector towards a competitive market environment. As long as Naftogaz is obliged to deliver gas at price below the cost-recovery level, its reorganisation, de-concentration and privatisation will not be possible.

Low energy prices are also counterproductive for reducing Ukraine’s energy dependence on Russia. In this context, the discussion on economic sanctions against Russia has limited merit as long as the international community is ready to support financially Ukraine’s overconsumption of Russian gas.

Unfortunately, despite a correct diagnosis, the IMF SBA sets only a very gradual price adjustment schedule with the aim of eliminating Naftogaz’s deficit only by 2018. The first round of tariff increases, for gas by 56 percent (from May 2014) and for district heating by 40 percent (from July 2014) looks drastic, but only if one disregards their very low initial level. In fact, the 2014 increase only compensates for the effect of UAH depreciation earlier this year. The next planned rounds of tariffs increases (by 40 percent in 2015 and by 20 percent in 2016 and 2017) might bring them closer to the cost-recovery level, but only if the UAH exchange rate and other cost components remain unchanged. And there is no certainty that the tariffs will reach the cost-recovery level even in 2017.

Oversized and inefficient welfare state

The general government total expenditure in Ukraine is close to the level of 50 percent of GDP, one of the highest in Europe and among emerging-market economies. In 2014, it might even exceed 50 percent of GDP. The biggest expenditure item is various social benefits (23.1 percent in 2013), of which public pensions account for 17.2 percent of GDP, again one of the highest shares in Europe and the world. The limited pension reform of 2011 (discussed previously) has stopped the growth in pension expenditure, but is unable to ensure system sustainability over the long term in the context of one of the least favourable demographic trends in Europe.

The retirement age, both statutory and effective, remains low by international standards and taking into consideration the rapid ageing of Ukrainian society. Numerous group privileges and special pension schemes offer opportunities for earlier retirement and generous benefits. As result, 13.6 million pensioners account for about one third of the Ukrainian population. This implies dependency ratio of 1 or higher.

Both the public components of benefits to better-off groups instead of lower-income groups. According to the World Bank’s Atlas of Social Protection, only 13.4 percent of total social-protection and labour-programme benefits went to the poorest 20 percent of the Ukrainian population in 2006.

What should be done?

Our analysis suggests there is an urgent necessity for the new Ukrainian authorities with the help and support of international community to elaborate a complex programme of far-going economic and institutional reforms. These should include both short-term measures of fiscal and macro-economic adjustment (much bolder than currently planned) and medium- to long-term structural and institutional changes. These are closely interlinked. For example, without removing energy subsidies, fiscal and balance-of-payments adjustment looks unrealistic and deeper reform of the energy sector (especially Naftogaz) cannot start, leaving serious distortions and sources of rents and corruption intact. Public pensions are a similar case: without increase in both the statutory and actual retirement age, the fiscal cost of the pension system will further expand, and labour market distortions and widespread informal employment will not be reduced.

Fiscal adjustment must play a central role in short-term policies, i.e. in 2014-15 because of deep dis-equilibria and sovereign insolvency risk. The concern that a too-radical fiscal adjustment can hurt growth prospects through the demand channel might not be justified in the Ukrainian economy in which eliminating distortions (for example, in the energy sector) and uncertainties (related to macroeconomic imbalances), and returning business confidence, can boost both investment and consumption. Long-term growth will be impossible without increasing the national savings rate, which requires, in first instance, the elimination of fiscal imbalances.

Discussion on the speed of reform must take into account both politics and economics. Obviously, fiscal adjustment which is crucial for rebuilding macroeconomic equilibrium and business confidence, will include politically unpopular measures, especially in relation to energy prices and the pension system. There will be social costs and various special interests will be threatened. How-ever, the unfavourable social consequences for the poor can be mitigated by well-targeted social safety nets. In turn, overcoming the resistance of special interest groups requires political mobilisation around the reform programme.

A time of geopolitical confrontation with a powerful neighbour might be considered to be an unlikely opportunity for difficult economic and political reform. However, Ukraine does not have any more time to waste. It must quickly rebuild confidence in its state institutions and economy. Perhaps the current patriotic mobilisation of Ukrainian society in the face of a threat to the country’s independence and after political change can create sufficient window of opportunity for difficult reforms.

Past experience tends to illustrate that such a window of opportunity is usually short-lived. Revolutionary mobilisation does not last long. People who do not see visible positive changes become disappointed, and enthusiasm is replaced by apathy and impatience. This opens door to populism and authoritarianism as experienced by Ukraine itself after the failure of the Orange revolution, or recently in Egypt. Easing social pain over longer period does not necessarily make life easier compared to a more radical and upfront reform package.

The resignation of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s government on 24 July 2014 with the objective of facilitating early parliamentary election in October 2014 might help build a stable pro-reform majority. However, it also means a further delay in implementation of reforms, and additional instability and uncertainty, which will accompany the forthcoming election campaign in the environment of the unresolved conflict in the east.

For international donors, the best strategy is to offer a substantial aid package to Ukraine (which has partly happened) but with more stringent conditions on reform compared to the current pack-age, and immediate technical assistance. This means upgrading the existing aid package built around the IMF SBA, EU and World Bank programmes to ensure faster macroeconomic adjustment in short-term and deeper institutional and structural reform in the medium-to long-term, backed by more international resources.