Blogs review: The rent affordability crisis

What’s at stake: San Francisco and the Google bus protests have become the symbols of gentrification and displacement in areas where the tech sec

What’s at stake: San Francisco and the Google bus protests have become the symbols of gentrification and displacement in areas where the tech sector has driven up housing costs. But the question of rental affordability is broader as rents have increased, while incomes have stagnated, over the past few years.

The shortage of affordable housing

Krishna Rao of Zillow Real estate Research writes that rapidly rising rents and stagnant incomes have made renting an expensive proposition across the country. Nationally, renters are spending more of their income on rent than they have at any point in the past 30 years. Historically in the United States, the median household would need to spend 24.9 percent of their income to afford the rent on the median property. Currently that number stands at 29.6 percent. In some parts of the country such as Los Angeles, Miami and San Francisco, the average household would need to spend over 40 percent of their income to rent the average home.

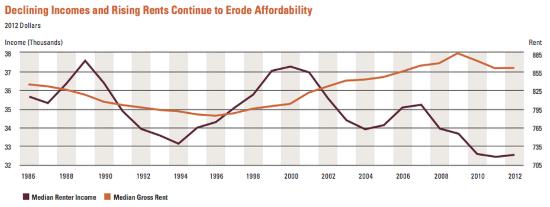

Source: Harvard

Jed Kolko writes that unlike buying, renting did not get significantly more affordable during the housing bust and recession. Rents rose throughout the recession or fell only modestly, depending on the measure you look at, even though incomes stagnated, and of course low mortgage rates don’t help renters. The recession caused rental demand to rise. Millions of people lost homes to foreclosure, and many of them became renters; in addition, many others put off their first-time home purchase and remained renters.

The Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University writes in a report that the recent economic turmoil underscored the many advantages of renting and raised the barriers to homeownership, sparking a surge in demand that has buoyed rental markets across the country. Households of all but the oldest age groups (75 and over) have joined in the shift toward renting. The largest increase in share is among the households in their 30s, up by at least 9 percentage points over an eight-year span.

In a long explainer on the SF housing crisis, Techcrunch writes that there is a major shift where cities and suburbs have traded places over the last 30 to 40 years. As people marry later and employment becomes more temporal, young adults and affluent retirees are moving into the urban core, while immigrants and the less affluent are moving out. San Francisco’s population hit a trough around 1980. But that out-migration reversed around 1980, and the city’s population has been steadily rising for the last 30 years. This is a phenomenon that’s happening to cities all over the United States. It’s happening in Seattle, Atlanta, New York City, Boston and Washington. D.C.

Regulation and depressed construction

Jed Kolko writes that the single best policy to improve rental affordability is to increase supply. The markets with the highest rents, like San Francisco and New York, tend to be difficult cities to build in: tight supply plus strong demand equals high rents. Zoning and other local regulations, as well as programs for financing affordable housing construction, all affect the ease and cost of building more units. Policies like rent control preserve affordability for current renters who are covered by the regulations but do little to affect rental affordability in the long run and could even worsen affordability if they end up discouraging new construction.

David H. Autor, Christopher J. Palmer, and Parag A. Pathak write that regulations are widespread in housing markets and rent control is arguably among the most important regulations historically. The modern era of U.S. rent controls began as a part of World War II-era price controls and as a reaction to housing shortages following demographic changes immediately after the war. Even though the prevalence of rent control as a housing market policy has decreased and rent stabilization and rent stabilization plans are still in place in many U.S. cities. New York City’s system of rent regulation affects at least one million apartments, while cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington DC, and many towns in California and New Jersey have various forms of rent regulation.

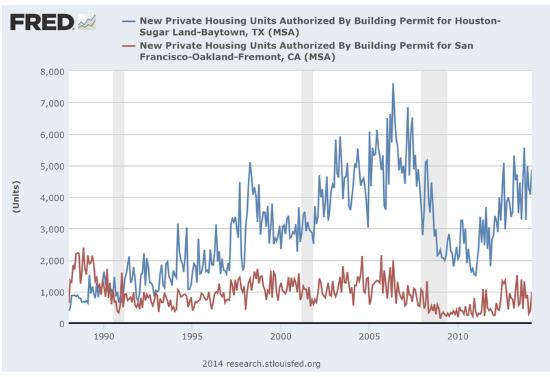

Matthew Yglesias writes that the reason residential construction is so depressed nationally is that most of the markets with strong housing demand make it extremely difficult, as a regulatory matter, to add additional housing units. Not that every area is bad in this regard. Look at the blue line below to see how rapidly the metropolitan area centered on Houston, Texas is adding housing units. Now look at the red line to see how rapidly — or, rather, slowly — the metro area centered on San Francisco is adding units. If it's profitable to build this many houses in Houston, it should be profitable to build even more houses in San Francisco.

Source: Vox.com

Ryan Avent writes that the welfare-maximizing population of San Francisco may be higher (and possibly much, much higher) than the population, which maximizes the welfare of those already living in San Francisco. So the city devises a set of regulations that effectively make current residents monopolists, able to artificially limit supply and raise price. Society as a whole is slightly worse off; San Franciscans are slightly better off.

High rents and the small contribution of housing to the recovery

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi write that the sensitivity of economic activity to rising house prices is much lower today than it was prior to the Great Recession.

Shaila Dewan writes that for many middle- and lower-income people, high rents choke spending on other goods and services, impeding the economic recovery. Low-income families that spend more than half their income on housing spend about a third less on food, 50 percent less on clothing, and 80 percent less on medical care compared with low-income families with affordable rents, according to a new report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Neil Irwin writes that the United States economy has been stuck in a vicious cycle: A moribund housing market saps the economy of strength, and the ensuing weakness — high unemployment, slow wage growth — means that fewer people are leaving the nest for a home of their own. Those who do are choosing smaller rental apartments that generate less spillover benefits for the broader economy.