Blogs review: Private debt in the US

What’s at stake: Discussions about the pace of monetary tightening have resurfaced following a recent speech by Board governor Jeremy Stein that

What’s at stake: Discussions about the pace of monetary tightening have resurfaced following a recent speech by Board governor Jeremy Stein that shows a worrying deterioration in lending standards. While private sector leverage has significantly increased over the last two years, the Swedish experiment in preemptive tightening illustrates the risk of using the blunt instrument of monetary policy when it comes to counteracting the build-up of financial bubbles.

Private sector leverage and the risk of a credit bubble

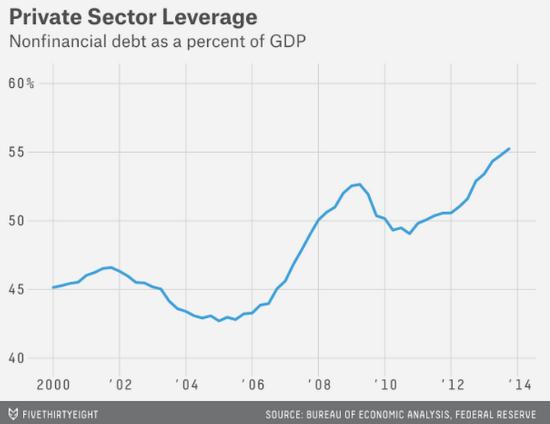

FiveThirtyEight reports that a recent speech by Jeremy Stein, with the wonky title “Incorporating Financial Stability Considerations into a Monetary Policy Framework,” garnered attention for its bold argument that the Fed should withdraw stimulus or raise interest rates to prevent the growth of a bubble — this time in the bond market, rather than in real estate or stocks. What are the signs of a bubble in the bond market? Stein points to three things: first, the rising level of private-sector debt as a percentage of the U.S. economy; second, narrowing spreads between risk-free Treasuries and corporate bonds; and third, the growing proportion of corporate debt going to riskier companies, i.e. companies that have a greater likelihood of defaulting on their loans.

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi writes that the financial stability concerns of Governor Stein and others are based on something more than just instinct. Stein, for example, cites the work of two Harvard Business School professors, Robin Greenwood and Samuel Hanson whose research argues that a good indicator of credit market overheating is the share of all new corporate debt issues coming from low-grade issuers. The high yield issue share peaks about two years before major meltdowns we’ve seen in credit markets. The high yield share in 2012 and 2013 indicates elevated risk, but not an impending disaster. For example, the 2013 high yield share is still below the peaks seen prior to other credit crashes. This may be driven in part by the fact that investment grade firms are also issuing a ton of debt. So in some sense the denominator is rising so fast that the high yield bond issues cannot keep up with it.

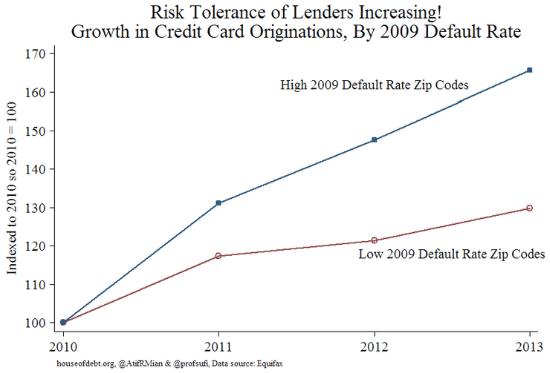

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi writes that lenders are showing an increasing willingness to take risk, especially over the last two years. The Federal Reserve Consumer Credit Statistical Release has shown strong growth in consumer debt (excluding mortgages). But this doesn’t necessarily mean that lenders are taking on more risk. They could be extending more credit to very high credit score individuals who are unlikely to default. But the microeconomic evidence suggests that the opposite is true: much of the growth in auto and credit card debt is among individuals most prone to default. We can see this using zip code level data. We split up zip codes in the United States into four groups based on their 2009 default rate. The groups each contain 25% of the population. The highest default rate zip codes tend to be those with the lowest credit scores. Credit card originations, for example, increased strongly in 2011. But after 2011, they more or less leveled out for zip codes with a low default rate in 2009. Instead, they continued to grow strongly in 2012 and 2013 in the riskiest zip codes.

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi writes that the critical question is whether the income prospects of individuals in riskier areas of the country warrant an increase in borrowing? Will they be able to pay back the debt when it comes due? During the subprime mortgage boom, our research shows that the answer to this question was clearly no. But what about now? Unfortunately, we do not have up-to-date data on the income of the riskiest borrowers. But we doubt that their income prospects have improved significantly–we haven’t seen the kind of strong job and wage growth that we would need to make sure that the riskiest borrowers have adequate income going forward.

In its latest Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF notes that the phenomenon of higher private sector debt is not limited to the US. Against the backdrop of low global interest rates and ample liquidity, net issuance of emerging market corporate debt tripled from 2009 to 2013. Debt at risk – the share of corporate debt held by weak firms – is well above precrisis levels in Asia and in emerging Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

The risk of tightening too early: The Swedish experiment

Lars Svensson writes that the deflation in Sweden has been caused by the Riksbank’s tight monetary policy since the summer of 2010. The majority of the executive board chose in the summer of 2010 to start increasing the policy rate, which was then at 0.25 percent. The policy rate was increased at a steady and fast rate to 2 percent in the summer of 2011. The increases started, in spite of the forecast in the summer of 2010 for inflation the next few years lying below the inflation target and the forecast for unemployment lying far above a long-run sustainable rate. The policy-rate increase caused the real policy rate (measured as the repo rate less HICP inflation, in order to be comparable across countries) to increase from minus 2.5 percent to plus 1 percent. This is a very large increase of 3.5 percentage points and was a very dramatic tightening of monetary policy.

Paul Krugman writes that Sweden, which faced none of the institutional constraints of the euro area, has managed to get itself into a deflationary trap. It’s an object lesson in the power of sadomonetarism, the desire of many monetary officials to raise interest rates because, well, because.

Paul Krugman writes that Sweden’s experience helps shed light on a historical controversy over US policy. There is a substantial contingent of Fed critics who insist that the whole bubble-bust cycle of the last decade was the Fed’s fault, that it kept interest rates too low for too long. If you think about it, however, the Fed circa 2003-2004 was facing a situation very similar to that of the Riksbank in 2010: unemployment still high but coming down, inflation low, and housing prices rising.