Blogs review: Wild Wild East

What’s at stake: Recent events in Ukraine have been and continue to be of great importance on a geopolitical scale. This review focuses on the ec

Read our comments on Ukraine and Russia 'Eastern promises: The IMF-Ukraine bailout', 'Interactive chart: How Europe can replace Russian gas', 'Can Europe survive without Russian gas?', 'The cost of escalating sanctions on Russia over Ukraine and Crimea', 'Russian roulette' and 'Gas imports: Ukraine's expensive addiction'

What’s at stake: Recent events in Ukraine have been and continue to be of great importance on a geopolitical scale. This review focuses on the economic dimension of the issue. Probably cut off from further Russian support, Ukraine faces urgent economic problems, particularly with regard to its international financial obligations and reviving its economy through reforms long overdue.

The core of Ukraine's issues

Timothy Tailor has a primer on Ukraine’s economic troubles. The country’s basic problem is that is has recurrently run large trade deficits, leading to occasional sharp devaluations. As the banking system, typically for a developing country, has mainly borrowed in foreign currencies, the major 2008 devaluation necessitated an IMF loan of $16.8 billion. Because reform progress was insufficient, when the cycle of trade deficits, capital inflows turning on and then off and distressed banks surfaced again in 2013, the IMF was unwilling to lend and Vladimir Putin stepped up with his plan to buy $15 billion in Ukrainian bonds and to offer lower natural gas prices.

Source: The Economist

The Economist’s Free Exchange adds that, as the global economic crisis led to a drought in capital flows, trying to protect the exchange rate, the central bank’s reserves declined to almost a quarter of their 2011 high before the central bank allowed the hryvnia to float, leading to a depreciation from 8:1 to 10:1 vs. the USD. Economic performance was rather dismal, too: In 2009 alone, GDP fell by 15%. Part of the current problem is that about half of Ukraine’s public debt is in foreign currencies and the depreciation thus has led to a rise of the debt stock. The solvency of the country is now less than secure and recent issuances of short-term debt required interest rates of around 15%.

Cardiff Garcia quotes an IIF paper that quantifies Ukraine’s total financing needs for this year at $25 bn: a projected $13bn current account deficit, $9bn in external debt repayments, and $3bn owed to Gazprom in natural gas payments. With currency reserves down to $12 bn in February and dwindling fast and Russia’s bailout on hold, a bailout package from some combination of the IMF, the EU, and the US or other friendly advanced-economy countries is now the only option to avoid a default.

The need for imminent economic measures

Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Gérard Roland argue that, aside from the long-run task of establishing a well-functioning democracy, which necessitates a new constitution and a popular referendum on it, the Ukrainian government needs to urgently implement emergency economic measures. First, the currency must be allowed to float (this is now the case) and depreciate significantly to fight the unsustainable 15% current account deficit. Second, through joint government and central bank action, the banking system should be provided with liquidity and capital. Third, the government must present a plan to address fiscal imbalances over a period of several years to restore confidence in the long-run solvency of the Ukrainian government. Fourth, it must deal with the heavy burden of external payments. Bringing in the IMF as well as other donors to assist in the short term – tens of billions of dollars will be required – would be helpful, but if that is unsuccessful, Ukraine should not exclude the option of default if external support is not coming. Finally, Ukraine should be prepared for a lengthy trade war with Russia, possibly necessitating energy imports from Europe and prepare short-term relief programmes for people and businesses who will be hit the hardest.

Timothy Tailor writes that Ukraine’s main problems now are its unwillingness to trim back energy subsidies and wage subsidies through the national energy company Naftogaz and a rather undiversified economy that is highly vulnerable to changes in steel and energy prices. However, there is a bright side to the situation: inflation is under control, unemployment is moderate at 8% and the public debt at 41% of GDP is not excessively high.

The Economist’s Free Exchange agrees with the priority to cut the massive energy consumption subsidies and adds that further areas urgently requiring reform are overspends on pensions and public sector wages, a massive shadow economy of up to 50% of GDP as well as extremely widespread corruption and tax evasion.

Long run reforms

Charles Wyplosz, in a piece from December 2013, comments that the deal struck between Yanukovich and Putin (lower gas prices and Russia buying Ukrainian bonds) meant that Ukraine did not have to agree to an IMF programme with its economic policy conditionality. Instead, the Russian deal probably came only with political, but without economic conditions and will harm both Ukraine and Russia in the long run. Ukraine will continue on an unsustainable path with high deficits, graft and heavy government intervention and Russia will eventually have to compensate its oil and gas exporters when Ukraine defaults on its loans.

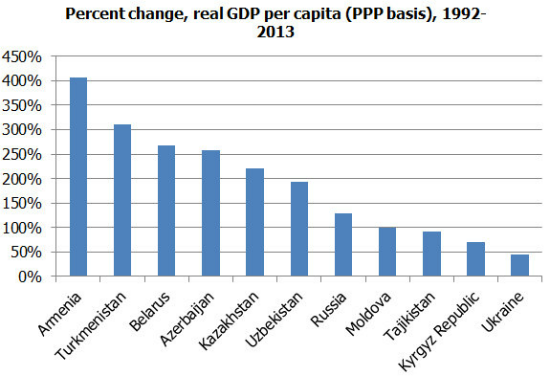

George Soros believes that Ukraine will now need outside assistance that only the EU can provide: management expertise and access to markets. Given its high-quality human capital and its diversified economy, Ukraine should be an attractive investment destination. Ensuring market access both for EU companies in Ukraine and vice versa and providing assistance to Ukrainian business managers, a repeat of the success story that was the transformation of the central European economies in the ‘90s, seems realistic.

Roger Myerson makes the case for political decentralization in Ukraine. The legitimacy of a presidential system much depends on the availability of suitable candidates for that office. But in Ukraine, the President has the power to choose all provincial governors. As in many countries, candidates for national leadership are regularly found among governors and mayors who have proven their abilities in the government of a province or a large city, constitutional reforms should be considered that would decentralize some share of responsible power to locally elected leaders in each province.

Which way to go? Ukraine, the EU and Russia

Walter Frick and Sarah Green compare the relative importance of the EU, Ukraine and Russia for one another as trading partners. The EU is a major buyer of Russian imports whereas only a small share of the EU’s exports go to Russia. Natural gas complicates matters, however: Russia as the world’s largest exporter of natural gas supplies 30% of Europe’s natural gas. And Ukraine is entirely sandwiched between the EU and Russia: Around 35% of its imports stem from Russia and about the same order of magnitude from European countries. The country will have to succeed at a delicate balancing act between the two poles. It cannot give up access to one without needing much more from the other.

Anders Aslund writes that the EU Association Agreement (EUAA) could be signed within one week and would amount to a comprehensive reform programme for Ukraine, with considerable help from EU state agencies. Opening up the European market to Ukrainian exporters would also attract more FDI into Ukraine. Concerning the threat of a trade war with Russia, a new understanding between Putin and Ukraine’s new leadership must be found that peaceful co-existence is in everyone’s best interests.

In an article from last November, Bernard Hoekman, Jesper Jensen and David Tarr argued that joining the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan would be an unwise choice for Ukraine, as it would impose strict conditions, for instance precluding Ukraine from negotiating free trade agreements with other countries. In order to deepen trade relations with the ECU, Ukraine should focus on integration of its companies in supply chains, which is now a major component of national competitiveness. Improving trade facilitation performance and related transport and communications services just halfway towards the global best practices could increase real incomes in Ukraine by 25% and increase exports by more than 50%. This together with some intergovernmental trade agreements would likely make the trade relations of Ukraine with the ECU closer than those with the EU, even if Ukraine should enter into a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade agreement (DCFTA) with the EU.

Natural gas and geopolitics

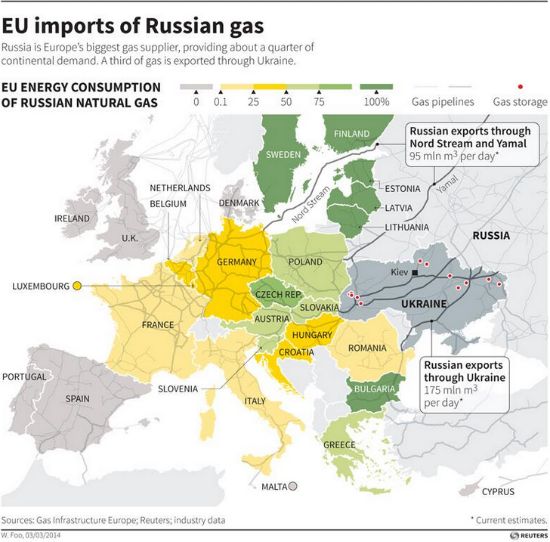

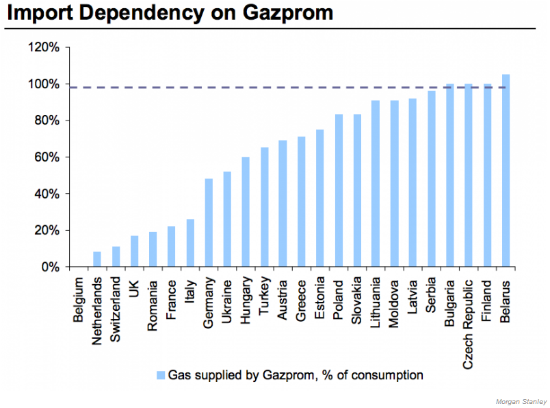

What is the strategic impact of Russia’s role as a major gas supplier for Europe in this conflict? Tyler Durden points out that Europe accounts for around a third of Gazprom's total gas sales, and around half of Russia's total budget revenue comes from oil and gas. Whatever Putin's geo-political ambitions, he probably does not want to jeopardize that source of revenue. However, although gas stocks are high in most EU countries thanks to a mild winter, many EU countries are extremely dependent on Russia for natural gas imports. With many pipelines used for shipping Russian gas to the EU running through Ukraine, a significant potential for Russian reactions to, say, EU sanctions, remains.

Source: @ReutersGMF

Source: Morgan Stanley through Zerohedge.

James Hamilton on Econbrowser adds that increasing US exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as asked for by some US politicians would hardly be an option to change the game: Even if more LNG facilities were approved, it would take years before gas could actually be delivered and even then it is inconceivable that the U.S. could ever replace the 7.4 trillion cubic feet of natural gas that Russia exported in 2012. At best, US exports could somewhat mitigate Europe’s vulnerability to gas supply disruptions.

Nick Butler writes that besides potentially seizing the Crimea, Moscow is in no position to confront Europe or even the new government in Kiev. Russia’s weakness is its overwhelming dependence on oil and gas export revenues. Russia exports 6m barrels of crude oil and another million barrels of oil products to Europe every day. Europe also buys a third of total Russian gas production. As the Russian economy is now more dependent on oil and gas than it was when Mr Putin came to power, Moscow simply cannot afford to lose any significant proportion of that revenue. Oil and gas account for 70 per cent of Russian exports and over 50 per cent of all state revenue.