Blogs review: Wage growth, spare capacity and rate hikes

What’s at stake: With central banks more pessimistic about the degree of economic slack and increasingly doubtful about the effectiveness of furt

What’s at stake: With central banks more pessimistic about the degree of economic slack and increasingly doubtful about the effectiveness of further growth in their balance sheets, the conversation has centered upon the developments that could trigger a first hike in interest rates. Together with the significant decrease in unemployment, the first signs of a recovery in wages have generated a growing sentiment that the tightening cycle might come earlier than what is currently priced.

Wage growth and the timing of the first hike

Gavyn Davies writes that it is likely that wages will emerge as the indicator that matters most for the FOMC. In the ongoing debate about how much spare capacity is left in the labor market, the behavior of wages is increasingly being viewed as decisive. Paul Krugman writes that a new conventional wisdom has taken hold over the past few months: economic slack is vanishing fast. Even though we still have huge unemployment, we’re actually running out of employable workers, and a dangerous acceleration in the pace of wage increases is already underway.

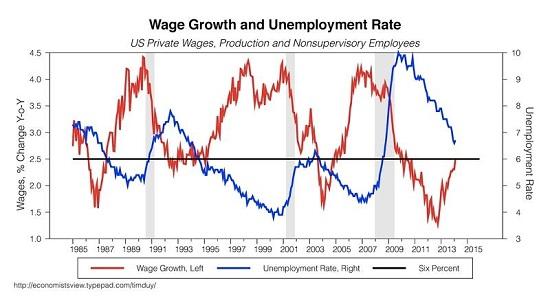

Tim Duy writes that the path of rates currently expected by policymakers assumes a great deal of slack. As a consequence, indications that slack is less than expected will tend to move forward the timing of the first rate hike and, perhaps the pace of subsequent tightening. Typically, the Fed tightens policy ahead of inflationary pressures, which, in practice, has meant hiking rates around the time wage growth bottoms out. So far the Federal Reserve is behaving just as they would in any other tightening cycle, with the only difference being that the first step is ending asset purchases rather than raising interest rates. So it is reasonable to believe that if they continue unwinding policy in a historically consistent manner, then there will not be a substantial pause between the end of asset purchases and the beginning of rate hikes. Historically, the Fed tightens before wages growth accelerates much beyond 2%.

Robin Harding writes that the argument that the Fed should overshoot on inflation is wrong. The overshooting argument, associated with Michael Woodford of Columbia University, goes roughly like this. When you are trapped at zero interest rates it is hard to stimulate the economy or generate inflation in the short-term. But what you can do is promise to allow some extra inflation in the future, once the economy has recovered. Knowing that extra inflation is coming lowers the real interest rate today and encourages more investment. To make this work the future inflation must be controlled, anticipated and credible. But that is totally different from saying it should overshoot on inflation, in an uncontrolled and unanticipated way, as the economy returns to full employment.

The evidence on wage pressures

Tim Duy writes that wage acceleration tends to occur as unemployment approaches 6%. Paul Krugman writes that there’s good reason to believe that everyone is working with the wrong paradigm here. Ever since the 1970s, textbook macroeconomics – reflecting the experience of the 1970s — has assumed an “accelerationist” framework, in which low unemployment leads not just to rising wages but to an ever-rising rate of wage increase. But the actual data haven’t looked like that for a long time. Since the mid-1990s, in fact, they have looked much more like an old-fashioned Phillips curve, with a relationship between the unemployment rate and the level of wage increase, not the rate of change of wage increase.

Paul Krugman writes that almost all the talk about rising wages is driven by just one labor market indicator, the average wage of nonsupervisory workers. Other wage indicators, like the average of all employees and the Employment Cost Index, are telling a different story.

Quit rates, vacancy chains and the role of long-term unemployed in wage determination

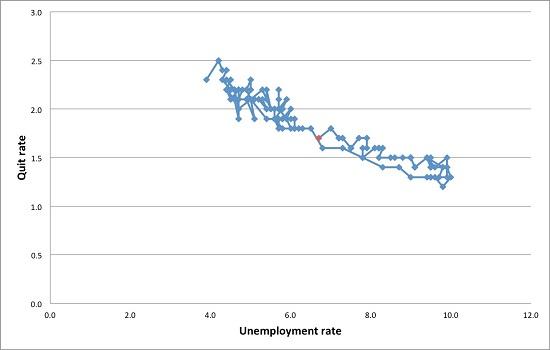

Evan Soltas writes that the U.S. is seeing 8 million too many quits a year for there to have been no reduction in slack in labor markets. That's 6 percent of total employment. In tighter labor markets, people tend to quit their jobs and find better ones. In looser labor markets, people cling to their jobs because unemployment is terrible. What the chart below shows is that we're seeing the expected number of people quitting their jobs given the current unemployment rate (the most recent data point is in red). What the graph suggests is that job-switchers don't think the long-term unemployed are any competition at all. If they were – if the unemployment rate overstated the amount of labor-market tightness – then we should have seen the relationship break down. In particular, the curve should have shifted downwards and to the left. There should be fewer quits for any given rate of unemployment.

Tim Duy writes that the dovish view is that the underemployed and long-term unemployed represent considerable slack. The hawkish view is that this is not a cyclical problem but a structural one. The long-term unemployed, by this theory, simply lack the currently needed skills. This is countered by indications of discrimination against the long-term unemployed. Such discrimination effectively means that you need to have a job to get a job. The ability of firms to engage in such discrimination could be viewed as a cyclical problem. Firms could not be so choosy in a stronger labor market. But evidence of the structural explanation can also be found in a comparison in the reasons for part time employment. Those employed part time for clearly cyclical reasons are falling. Those employed part time because they could not find full time work is holding steady. It may be that the skill set of those workers is not consistent with the current types of full time jobs.

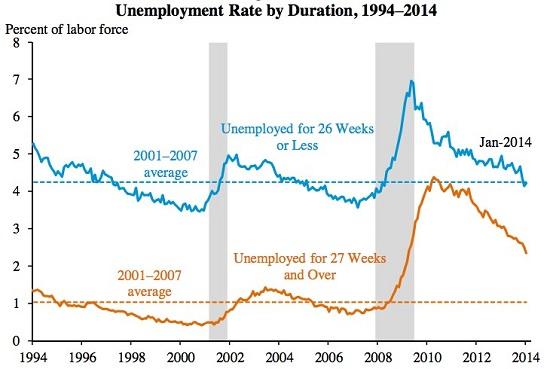

Source: Economic Report of the President 2014

Henry Linder, Richard Peach, and Robert Rich writes that the hypothesis that individuals who are unemployed for long durations have less impact on the behavior of wages than the recently unemployed is not new. Insider-outsider models make this prediction, and a paper by Ricardo Llaudes finds strong support for this proposed explanation in data for European countries. What is new is the relevance of this hypothesis for movements in wage rates in the United States. The authors write that the distinction between short-duration and long-duration unemployment has received very little attention in the United States previously because of the close correspondence between the total unemployment rate and the short-duration unemployment rate.

Mike Konczal writes that the only thing interesting about the quits rate is what it is implying about the length and conclusion of vacancy chains. If the length of the vacancy chain is infinitely increasing, then wage growth must be skyrocketing. And if the unemployed aren’t capable of taking jobs and closing the vacancy chain, then the number of job openings must rise relative to the unemployment rate. Which means the interesting things the quits rate tells us about unemployment are entirely captured in wage growth or the number of job openings relative to unemployment (i.e. the Beveridge Curve).