Blogs review: The labor market effects of Obamacare

What’s at stake: This week’s controversy came from an 11-page appendix published on Tuesday by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), w

What’s at stake: This week’s controversy came from an 11-page appendix published on Tuesday by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which revised its estimate of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA or Obamacare) impact on labor markets. In 2010, CBO estimated that the ACA would reduce the amount of labor used in the economy by roughly half a percent. On Tuesday, the budget office revised its estimates by a factor of 3, which would translate into a reduction of full-time equivalent employment of 2.5 million people.

A decline in labor supply, rather than in labor demand

Greg Ip notes that the White House Council of Economic Advisers, in a lengthy analysis in 2009, predicted the Affordable Care Act “would likely increase labor supply,” by reducing absenteeism and disability. The disincentive “effects of subsidized health insurance premiums on aggregate labor supply would be modest.” The White House did trumpet the reduction in "job lock" that came from delinking health care and employment, but only in the context of encouraging people to leave one job for another, not to leave work altogether.

The CBO writes that the estimated reduction stems almost entirely from a net decline in the amount of labor that workers choose to supply, rather than from a net drop in businesses’ demand for labor.

Josh Barro writes that the law will reduce work hours through several mechanisms, some of which are desirable and some of which aren't. Obamacare will discourage people from working in two main ways: through "income effects" (which is desirable) and "substitution effects" (which is bad). When you give a person a subsidized health plan, you raise that person's real income, making it easier for him to quit his job, work fewer hours, or take a job that doesn't offer insurance. If you phase out that person's health insurance subsidy with rising income, you encourage him to work less, and instead substitute non-taxed activities, such as leisure or child-rearing. Importantly, this substitution is a distortion: In absence of the tax, the worker would have preferred to work and earn his pre-tax wage, rather than spend time on something else.

Trade-offs for everything

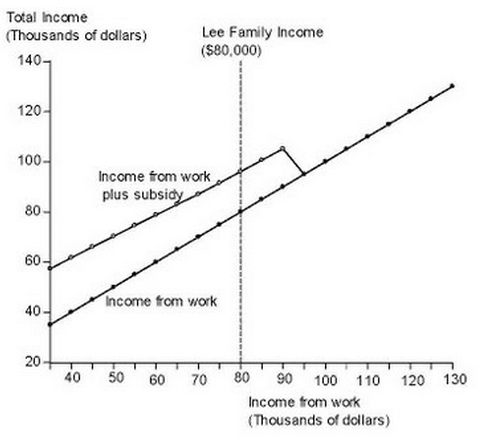

John B. Taylor illustrates the work disincentive effects of the subsidy cliff at 400% of the poverty line. The graph shows income from work and the corresponding health care subsidy for a family of 4 headed by a 55-year old. The subsidy is paid to households earning up to 400 percent of the poverty line. With a poverty line of about $23,300 for a family of 4 in 2014 (when the legislation goes into effect) families earning as much as $93,200 will get a subsidy. Observe how the subsidy declines with income and then is slashed to zero when 400 percent of the poverty line is hit. You can even see the V-shaped “notch” in the graph, which has become the technical term used to describe such sudden drops in subsidies. Consider the Lee family, for example. They earn $80,000 and thus get a subsidy of $16,100, bringing their total income to $96,100. But suppose they decide to work more. If they increase their income from work by $14,000, bringing their work earnings to $94,000, then their health care subsidy drops to zero. So they get less income by working more, and that’s a big disincentive.

Source: John B. Taylor

Kevin Drum writes that this is not something specific to Obamacare. It's a shortcoming in all means-tested welfare programs. It's basically Welfare 101, and in over half a century, no one has really figured out how to get around it. It's something you just have to accept if you support safety net programs for the poor. Josh Barro points that the Republican Coburn-Burr-Hatch Obamacare alternative has the same features, and so would also reduce employment relative to the pre-Obamacare status quo.

Austin Frakt writes that some of the work disincentives of Obamacare could be tweaked (ditch the employer mandate, design a smoother glide path off subsidies, etc.) but at some taxpayer cost. Taxes also impose an economic drag. Choose your poison.

The literature on labor supply effects of medical coverage expansion

The CBO argues that part of its revision is due to recent studies, which have pointed to a larger effect on labor supply than CBO had estimated previously.

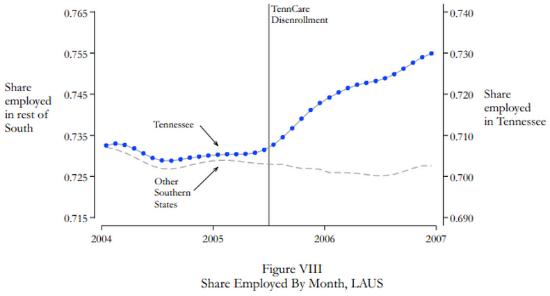

Sarah Kliff writes in Wonkblog’s Health Reform Watch that if you want to understand the newest Obamacare projection coming out of Washington the best place to start might be Tennessee. Back in 2005, Tennesse's Medicaid program was facing a shortfall, and the state abruptly halted coverage for 170,000 low-income adults, a population that the state was not required to cover. This dramatic coverage cut was a rare event. And it gave Craig Garthwaite, a health economist at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Business, the opportunity to probe what's become an increasingly important question: Does the availability of government-funded insurance effect employment? Garthwaite's findings suggest that it does, potentially to a strong degree.

Source: Sarah Kliff

Sarah Kliff writes that the body of research on how health insurance expansion affects labor force participation is, however, far from complete. A study on Oregon’s 2008 Medicaid expansion, which the state conducted by lottery – creating a random sample of people who wanted coverage but didn't get it and those who did get coverage, found that Medicaid has no detectable effect on employment.

Good or bad?

Democracy in America writes that when people choose to work less it is not immediately clear whether this is a good or bad thing. For example: good or bad for who, those workers or the rest of society? What new benefits are the workers getting under this system? What will they be doing with the extra time not spent working? How valuable to the rest of society is the extra labor they have taken off the market, compared to the benefits they are receiving and the value of their newfound free time?

Paul Krugman writes that the predicted long-run fall in working hours isn’t entirely a good thing. Workers who choose to spend more time with their families will gain, but they’ll also impose some burden on the rest of society, for example, by paying less in payroll and income taxes. So there is some cost to Obamacare over and above the insurance subsidies. Any attempt to do the math, however, suggests that we’re talking about fairly minor costs, not the “devastating effects” asserted.

Ross Douthat writes that there are also lots of people who emphatically do not benefit from being given an incentive to detach from the workforce. And given the current economic landscape, especially — in which persistently high unemployment coexists with a growing population of workers too discouraged to even look for work — the size and scope of a work-discouraging effect matters a great deal: The bigger the effect, the more likely that the people dropping out aren’t just, say, parents cutting hours to spend more time at home while the other spouse works full time, but people we should want to be attached to the workforce, for their own long-term good and the good of the economy as well.